Lisa recently posted about Abercrombie Kids selling push-up bikini tops (though I just went to the website and they seem to have removed the “push-up” description). In another example of encouraging pre-teens to sexualize their bodies, Meghan L. sent in the clip “You’ve Got Snooki” from AOL Video in which Snooki, from Jersey Shore, does a makeover on an 11-year-old girl, since you’re “never too young to look bangin'” or to start thinking about how you look to boys:

gender: children/youth

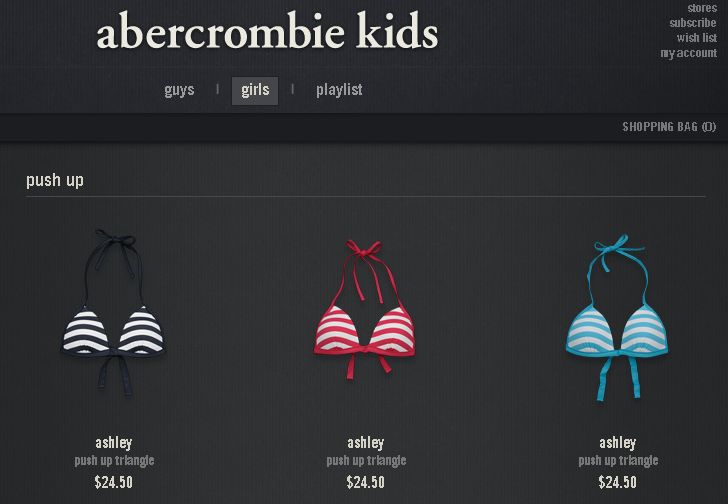

Allison K. sent in another example of the sexualization of young girls. Abercrombie Kids is selling bikinis with “push-up” tops. According to Wikipedia, the company markets its products at kids age 7-14. The average age of puberty is 12. So, at what age should girls start trying to enhance their cleavage? How old is too young?

UPDATE: In the last week this post was shared and tweeted by many of you. News outlets took up the issue and, in response to the public pressure, Abercrombie first changed the language (taking out the phrase “push up” and just leaving “triangle”), then took the product off the site altogether. On their Facebook page, they wrote that “We agree with those who say it is best ‘suited’ for girls age 12 and older.”

For more on the sexualization of young girls, see our posts on sexually suggestive teen brands, adultifying children of color, “trucker girl” baby booties, “future trophy wife” kids’ tee, House of Dereón’s girls’ collection, 6-year-olds in French Vogue, “is modesty making a comeback?“, more sexualized clothes and toys, sexist kids’ tees, a trifecta of sexualizing girls, a zebra-striped string bikini for infants, a nipple tassle t-shirt for girls, even more icky kids’ t-shirts, “are you tighter than a 5th grader?” t-shirt, the totally gross “I’m tight like spandex” girls’ t-shirt, a Halloween costume post, Toddlers and Tiaras, and girls in the World of Dance tour.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Jezebel.

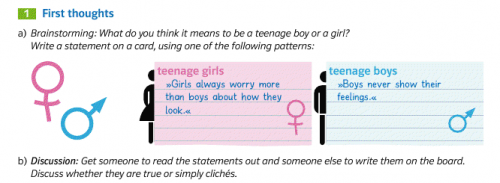

Andi S.-R. noticed an interesting segment in a German textbook used to teach English. In the last few years, 12th-grade English classes have started including a section about gender, so textbooks have added chapters on the topic. Andi found a supplement from Klett, one of the major German publishers of educational materials, provided a supplement for covering gender that included a brainstorming exercises. While the idea was to foster discussion about gender stereotypes, Andi questions whether the sample comments provided as examples would help with that goal or would prime students to focus on stereotypical behavior by providing it as a model:

A second section helpfully suggests “bitchiness” as a quality students might associate with girls:

Again, the idea is to promote discussion, an excellent goal. But Andi succinctly points out the potential pitfalls of such a superficial approach:

…it’s unclear how students are supposed to know if these are “views” or “facts”, and having a discussion based on gut-feeling alone seems only likely to reinforce and teach as “facts” those stereotypes the students are familiar with, anyway.

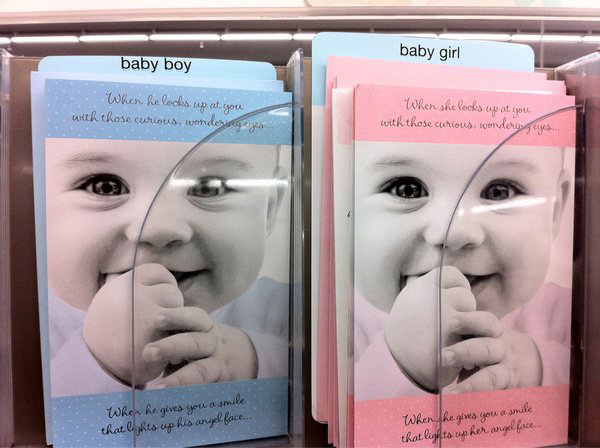

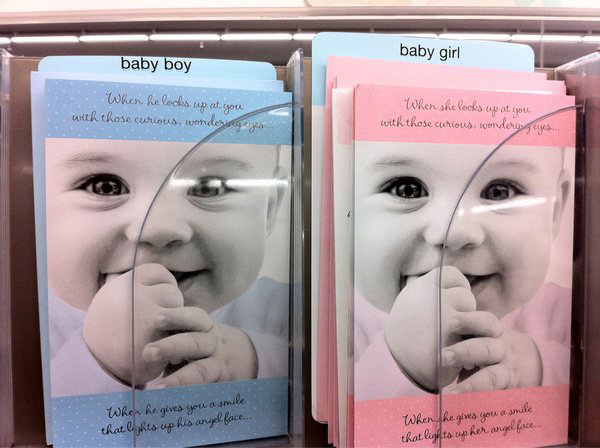

There is something so damn ironic about this pair of greeting cards photographed by Julie Becker from Lansing, Mich. The cards, designed to congratulate new parents on the birth of their child, reveal a (perceived) desire to gender our infants from Day One. It is important to identify this child’s gender; it must be noted and color-coded that it is a “he” or a “she.” But the card company finds no irony in using exactly the same baby on each card:

In fact, gendering infants is a rather new phenomenon in Western history and not cross-culturally consistent. Some cultures, and in Western culture previously, the sex of children was considered rather irrelevant until puberty.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Joanna S. sent us a link to an application designed by Jonathan McIntosh where one can “re-mix” toy commercials aimed at boys versus girls. You choose the visuals of one and the sounds of another, and have fun watching the wackiness. We can’t embed the fun results, but you might enjoy visiting and playing a few for fun.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Nicole S. sent in this great example of the way that differences in bodies are used to infer a wide-range of non-anatomical differences between boys and girls (or, in this case, the other way around).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Elisabeth R., Rebecca H., and Kalani R. all sent in a Volkswagen commercial produced for SuperBowl weekend that they found striking, both for the commercial itself and reactions to it. In the commercial, a child dressed up as Darth Vader tries using The Force on various items around the house. What struck all three of the submitters is the ambiguous gendering of the ad:

At no point is the child’s gender made clear. If we just went with the information in the ad, we might conclude the child is a girl, based on scene in the stereotypically super-pink bedroom. But given the usual clear gendering of toys, Elisabeth, Rebecca, and Kalani all enjoyed seeing an ad in which this didn’t occur.

But the possibility that a girl might dress up as Darth Vader seems difficult for a lot of people to grasp. In the pages and pages of comments on the commercial on YouTube, the child is repeatedly referred to as “he” or “the boy.” In one comment thread, when someone brings up the possibility the child is a girl due to the pink bedroom, someone else says no, it was a boy in his sister’s room.

There’s no particular reason to assume this child is a boy except that we associate Star Wars with boys (and generally see males as the default if gender isn’t otherwise specified). I think the reactions to the video are a good example of the power of gendering: because viewers have pre-existing ideas about gender, kids, and what they’d be interested in, they’re likely to apply those assumptions even in the face of potentially contradictory information and to come up with explanations that leave the pre-existing ideas intact.

UPDATE: I forgot to mention when I was writing the post that none of the commenters who saw the child as a boy seemed to think the pink room was his — I read several different comment threads and when it was brought up, people assume it’s a sister’s room. Also, reader Angie thinks the stuff in the pink room looks too old for the child, since the toys look like the type an older kid would collect. I am clueless about that, which is why I struggle to buy gifts for kids: I no longer have a clear sense of what types of things kids are playing with at what age.

UPDATE 2: This is separate from what the gender of the role of the child in the commercial, but VW has confirmed that the actor who played the child is a boy.

On another note, the fact that VW is using Star Wars nostalgia in its ads as a way to appeal to adult customers makes me feel very old for some reason.

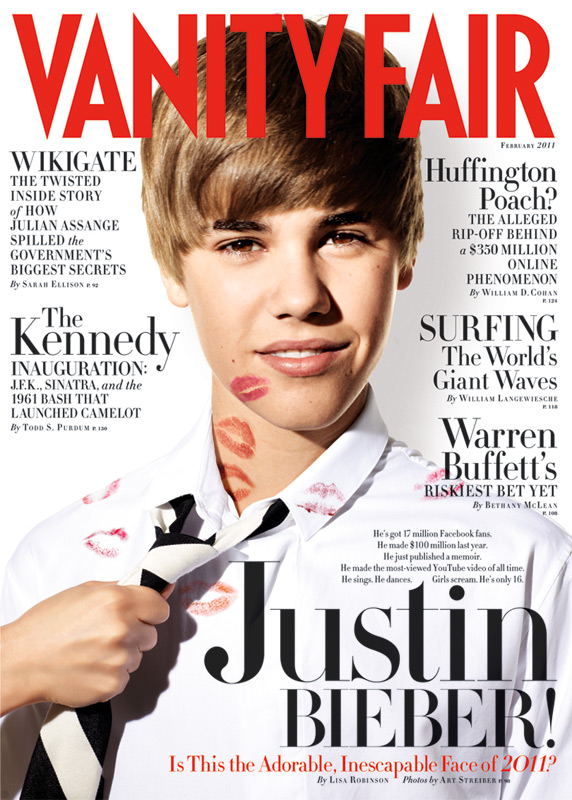

Kari B. sent in an example of the sexualization of teen boys, found at Evil Slutopia. Justin Bieber appears on the cover of the February 2011 Vanity Fair covered in lipstick, with a hand grabbing him by his necktie:

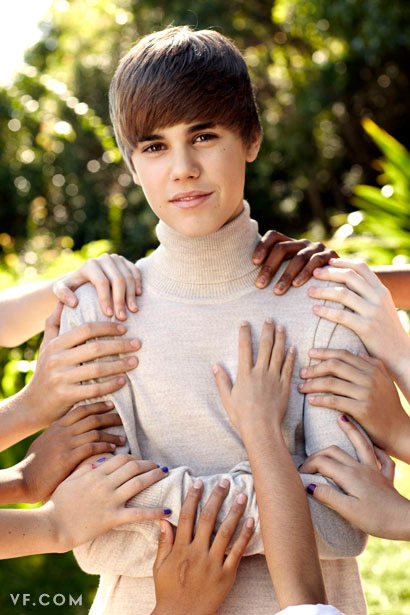

An image from the article:

Justin Bieber is 16 years old — just a year older than Miley Cyrus was when there was a scandal about her photoshoot for Vanity Fair, such that it appeared to potentially threaten her career at Disney by ruining her safe, clean-cut image. I think it’s safe to say that if Miley Cyrus, or another female teen star, posed in photos that showed evidence of being kissed or grabbed by male fans, people would be up in arms about the sexualization of girls. But as we often see, there’s a double-standard, based on the idea that boys are naturally sexual at earlier ages and that boys are sexually invincible. While we might see a teen girl surrounded by men as being in danger, we don’t think of girls as being sexually threatening to boys, or of male teen celebrities’ sexuality being as open to exploitation by publicists, photographers, or other members of the media. And thus, these types of images of Justin Bieber don’t lead to the same outcry as similar images of female teen stars, and don’t cause concern that his career as a teen idol is over.

We’ve discussed the adultification of Justin Bieber before, here and here; you might also check out our post on the sexualization of Jaden Smith.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

Allison K. sent in another example of the sexualization of young girls. Abercrombie Kids is selling bikinis with “push-up” tops. According to Wikipedia, the company markets its products at kids age 7-14. The average age of puberty is 12. So, at what age should girls start trying to enhance their cleavage? How old is too young?

UPDATE: In the last week this post was shared and tweeted by many of you. News outlets took up the issue and, in response to the public pressure, Abercrombie first changed the language (taking out the phrase “push up” and just leaving “triangle”), then took the product off the site altogether. On their Facebook page, they wrote that “We agree with those who say it is best ‘suited’ for girls age 12 and older.”

For more on the sexualization of young girls, see our posts on sexually suggestive teen brands, adultifying children of color, “trucker girl” baby booties, “future trophy wife” kids’ tee, House of Dereón’s girls’ collection, 6-year-olds in French Vogue, “is modesty making a comeback?“, more sexualized clothes and toys, sexist kids’ tees, a trifecta of sexualizing girls, a zebra-striped string bikini for infants, a nipple tassle t-shirt for girls, even more icky kids’ t-shirts, “are you tighter than a 5th grader?” t-shirt, the totally gross “I’m tight like spandex” girls’ t-shirt, a Halloween costume post, Toddlers and Tiaras, and girls in the World of Dance tour.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Cross-posted at Jezebel.

Andi S.-R. noticed an interesting segment in a German textbook used to teach English. In the last few years, 12th-grade English classes have started including a section about gender, so textbooks have added chapters on the topic. Andi found a supplement from Klett, one of the major German publishers of educational materials, provided a supplement for covering gender that included a brainstorming exercises. While the idea was to foster discussion about gender stereotypes, Andi questions whether the sample comments provided as examples would help with that goal or would prime students to focus on stereotypical behavior by providing it as a model:

A second section helpfully suggests “bitchiness” as a quality students might associate with girls:

Again, the idea is to promote discussion, an excellent goal. But Andi succinctly points out the potential pitfalls of such a superficial approach:

…it’s unclear how students are supposed to know if these are “views” or “facts”, and having a discussion based on gut-feeling alone seems only likely to reinforce and teach as “facts” those stereotypes the students are familiar with, anyway.

There is something so damn ironic about this pair of greeting cards photographed by Julie Becker from Lansing, Mich. The cards, designed to congratulate new parents on the birth of their child, reveal a (perceived) desire to gender our infants from Day One. It is important to identify this child’s gender; it must be noted and color-coded that it is a “he” or a “she.” But the card company finds no irony in using exactly the same baby on each card:

In fact, gendering infants is a rather new phenomenon in Western history and not cross-culturally consistent. Some cultures, and in Western culture previously, the sex of children was considered rather irrelevant until puberty.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

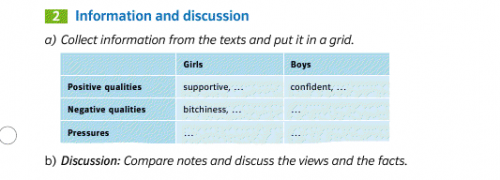

Joanna S. sent us a link to an application designed by Jonathan McIntosh where one can “re-mix” toy commercials aimed at boys versus girls. You choose the visuals of one and the sounds of another, and have fun watching the wackiness. We can’t embed the fun results, but you might enjoy visiting and playing a few for fun.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Nicole S. sent in this great example of the way that differences in bodies are used to infer a wide-range of non-anatomical differences between boys and girls (or, in this case, the other way around).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Elisabeth R., Rebecca H., and Kalani R. all sent in a Volkswagen commercial produced for SuperBowl weekend that they found striking, both for the commercial itself and reactions to it. In the commercial, a child dressed up as Darth Vader tries using The Force on various items around the house. What struck all three of the submitters is the ambiguous gendering of the ad:

At no point is the child’s gender made clear. If we just went with the information in the ad, we might conclude the child is a girl, based on scene in the stereotypically super-pink bedroom. But given the usual clear gendering of toys, Elisabeth, Rebecca, and Kalani all enjoyed seeing an ad in which this didn’t occur.

But the possibility that a girl might dress up as Darth Vader seems difficult for a lot of people to grasp. In the pages and pages of comments on the commercial on YouTube, the child is repeatedly referred to as “he” or “the boy.” In one comment thread, when someone brings up the possibility the child is a girl due to the pink bedroom, someone else says no, it was a boy in his sister’s room.

There’s no particular reason to assume this child is a boy except that we associate Star Wars with boys (and generally see males as the default if gender isn’t otherwise specified). I think the reactions to the video are a good example of the power of gendering: because viewers have pre-existing ideas about gender, kids, and what they’d be interested in, they’re likely to apply those assumptions even in the face of potentially contradictory information and to come up with explanations that leave the pre-existing ideas intact.

UPDATE: I forgot to mention when I was writing the post that none of the commenters who saw the child as a boy seemed to think the pink room was his — I read several different comment threads and when it was brought up, people assume it’s a sister’s room. Also, reader Angie thinks the stuff in the pink room looks too old for the child, since the toys look like the type an older kid would collect. I am clueless about that, which is why I struggle to buy gifts for kids: I no longer have a clear sense of what types of things kids are playing with at what age.

UPDATE 2: This is separate from what the gender of the role of the child in the commercial, but VW has confirmed that the actor who played the child is a boy.

On another note, the fact that VW is using Star Wars nostalgia in its ads as a way to appeal to adult customers makes me feel very old for some reason.

Kari B. sent in an example of the sexualization of teen boys, found at Evil Slutopia. Justin Bieber appears on the cover of the February 2011 Vanity Fair covered in lipstick, with a hand grabbing him by his necktie:

An image from the article:

Justin Bieber is 16 years old — just a year older than Miley Cyrus was when there was a scandal about her photoshoot for Vanity Fair, such that it appeared to potentially threaten her career at Disney by ruining her safe, clean-cut image. I think it’s safe to say that if Miley Cyrus, or another female teen star, posed in photos that showed evidence of being kissed or grabbed by male fans, people would be up in arms about the sexualization of girls. But as we often see, there’s a double-standard, based on the idea that boys are naturally sexual at earlier ages and that boys are sexually invincible. While we might see a teen girl surrounded by men as being in danger, we don’t think of girls as being sexually threatening to boys, or of male teen celebrities’ sexuality being as open to exploitation by publicists, photographers, or other members of the media. And thus, these types of images of Justin Bieber don’t lead to the same outcry as similar images of female teen stars, and don’t cause concern that his career as a teen idol is over.

We’ve discussed the adultification of Justin Bieber before, here and here; you might also check out our post on the sexualization of Jaden Smith.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.