Cross-posted at Montclair Socioblog.

In the New York Times, Arthur Brooks argues that conservatives are happier than liberals.

Brooks starts with a reference to Barack Obama’s remark four years ago about “bitter” blue-collar Whites who “cling to guns or religion.” Misleading, says Brooks. So is a large body of research showing conservatives as “authoritarian, dogmatic, intolerant of ambiguity, fearful of threat and loss, low in self-esteem and uncomfortable with complex modes of thinking.”

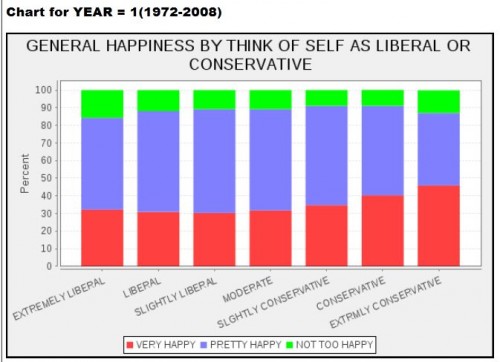

Despite that research, it’s conservatives, not liberals, who identify themselves as happy. And, Brooks adds, the farther right you go on the political spectrum, the more happy campers you find.

Brooks cites a couple of surveys that support this view. I was a bit skeptical, so I went to the GSS.

Sure enough, by about 10 percentage points, more conservatives identify themselves as “very happy” than do liberals. The difference is even higher among the extreme conservatives. As Brooks says, “none, it seems, are happier than the Tea Partiers, many of whom cling to guns and faith with great tenacity.”

Sure enough, by about 10 percentage points, more conservatives identify themselves as “very happy” than do liberals. The difference is even higher among the extreme conservatives. As Brooks says, “none, it seems, are happier than the Tea Partiers, many of whom cling to guns and faith with great tenacity.”

Brooks cites two important factors linking political views and happiness: marriage (with children) and religion.

Religious participants are nearly twice as likely to say they are very happy about their lives as are secularists (43 percent to 23 percent). The differences don’t depend on education, race, sex or age; the happiness difference exists even when you account for income.*

I still found it hard to reconcile these sunny right-wingers with the image of bitter and angry Tea Partiers. Then I remembered that the Tea Party is a very recent phenomenon. To a great extent, it’s a reaction to the election of President Obama. But Brooks is looking at pre-Obama studies of happiness. The most recent one he cites is from 2006. As the GSS graph above shows, Brooks is correct when he says, “This pattern has persisted for decades.” But those decades don’t include the Tea Party.

Maybe conservatives were happy because until recently, they didn’t have much to be bitter about. The US was their country, and they knew it. Then Obama was elected, and ever since November 2008 conservatives have kept talking about “taking back our country.” (See my “Repo Men” post from 2 1/2 years ago.)

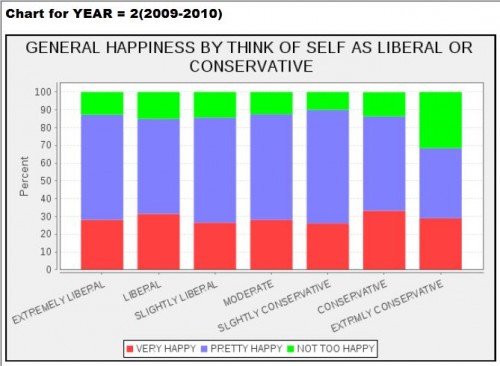

What if we look at the data from the Obama years?

Maybe that bitter Tea Party image isn’t such a distortion. The GSS does not offer “bitter” or “Tea Party” as choices, but those who identify themselves as “extreme conservative” are nearly three times as likely as others to be “not too happy.” And overall, the happiness gap between conservatives and liberals is hard to find.

Maybe that bitter Tea Party image isn’t such a distortion. The GSS does not offer “bitter” or “Tea Party” as choices, but those who identify themselves as “extreme conservative” are nearly three times as likely as others to be “not too happy.” And overall, the happiness gap between conservatives and liberals is hard to find.

For all I know, Brooks’s general conclusion may be correct, but the recent data do at least raise some questions and suggest that the political context is itself a relevant variable.

Nearly eighty years ago, Harold Lasswell said that politics is about “who gets what, when, and how.” Maybe the lesson here is that if you are going to study the connection between political views and happiness, you should take account of who is getting what, and when.

*That’s a bit misleading. Happiness is in fact related to income, race, and education in exactly the ways you would expect, though for some reason Brooks does not include those variables in his analysis. What Brooks means is that the religion effect holds even when you control for those variables.

—————————

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.