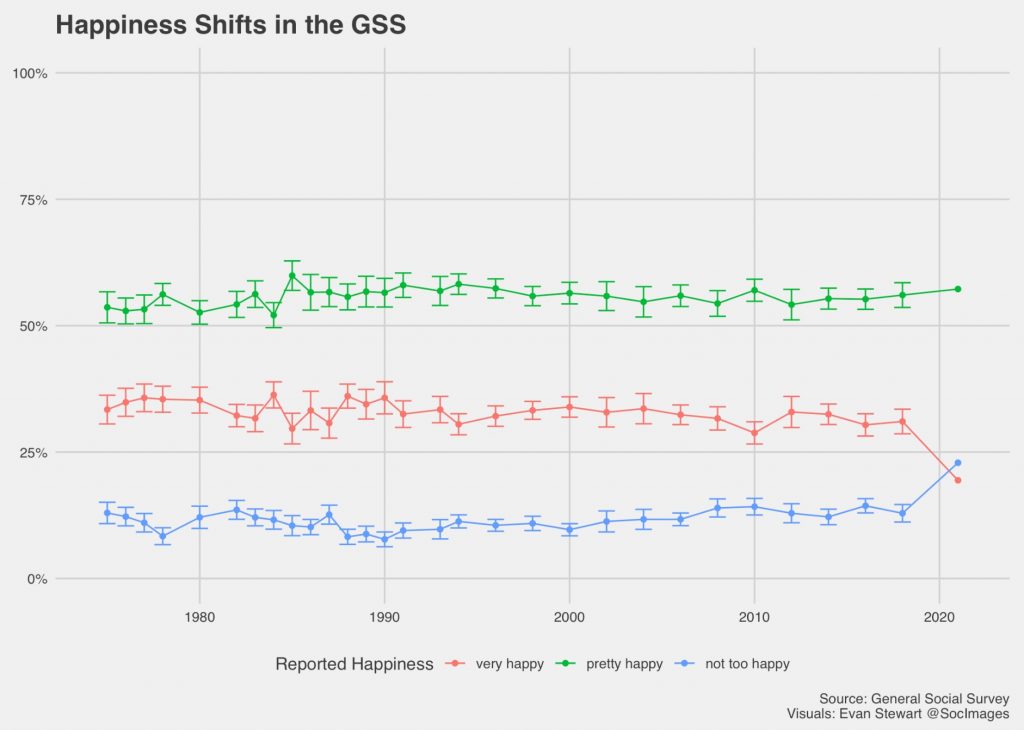

As the new year brings in a new peak in COVID cases across the country, we all have a right to feel a little down in the dumps.

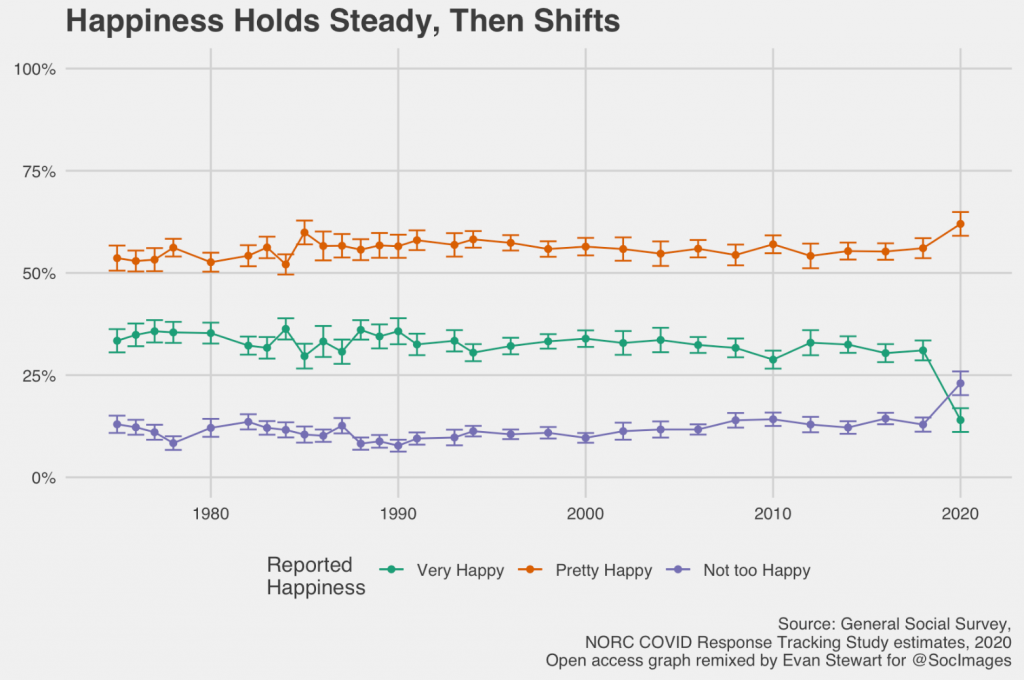

One trend picked up by surveys earlier in the pandemic was a drop in self-reported happiness. Now, with a new year of General Social Survey data released, it looks like the trend continues.

I’ve been thinking a lot about happiness and wellbeing as I launch into teaching Introduction to Sociology this year, both because we want to do right by our students in a tough time and because new students thinking about majoring have a right to ask us: how is our field helping the world?

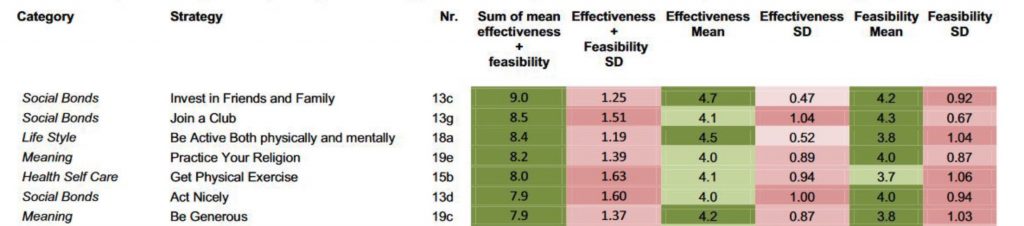

That’s why I was especially hopeful to hear about this study making its way around Twitter. The authors conducted interviews and surveys with experts in the field of happiness research to rank the things they thought would be most likely to increase life satisfaction based on their understanding of the research literature. Two important points caught my attention.

First, the researchers ranked both personal solutions and policy solutions to improve life satisfaction. This is important because we often think about our own happiness as an individual experience and an individual effort (often bolstered by the self-help industry). Focusing on policy reminds us that our individual wellbeing is linked to collective wellbeing, too.

Second, many of these experts’ top ranked solutions were explicitly about social relationships. For personal solutions, two of the top ranked suggestions were investing in friends and family and joining a club. For policy solutions, some of the top answers included promoting voluntary work or civil service and reducing loneliness.

Expert consensus studies like this have a lot of limitations, since they only show us a glimpse of the current conventional wisdom. But this study also shows us the positive stakes of sociology. It reminds us that developing a better understanding of our relationships and investing in those relationships is not just a self-help fad; it can be a social policy priority to get us through tough times together.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.