Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

The politics of motherhood reared its head again last month when Hilary Rosen, who the news identified as a “Democratic strategist,” said that Ann Romney (Mrs. Mitt) had “never worked a day in her life.” (A NY Times article is here.)

“Worked” was a bad choice of words. Raising kids and taking care of a home are work, maybe even if you can hire the kind of help that Mrs. Romney could afford. Rosen’s comment implied that family work is not as worthwhile as work in the paid labor force. That’s not such an unreasonable conclusion if you assume that we put our money where our values are and reward work in proportion to what we think it’s worth. Mitt’s supporters use this value-to-society assumption to justify the huge payoffs Romney derived from those leveraged buyouts at Bain Capital.*

Even Mrs. Romney apparently felt that there must be some truth to the enviability of a career. Why else would she refer to stay-at-home motherhood as a career? “My career choice was to be a mother.”

Still, regardless of the truth of Rosen’s remark, it was insulting.** Stay-at-home motherhood is work – a job.

But is it a good job?

A recent Gallup poll provides some more evidence as to why stay-at-home moms might be both envious or resentful of their employed counterparts. Gallup asked women about the emotions, positive and negative, that they had felt “a lot” in the previous day. Gallup then compared the stay-at-home moms, employed moms, and employed women who had no children at home.

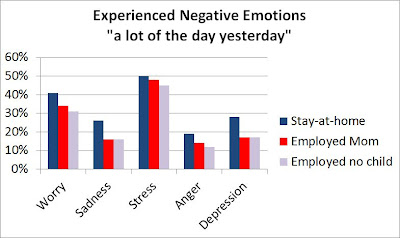

The stay-at-home moms came in first on every negative emotion. Some of the differences are small, but the Gallup sample was more than 60,000 so these differences are statistically significant. The smallest difference was for Stress – no surprise there, since paid work can be stressful. Worry and Anger too can be part of the workplace. The largest differences were for Sadness and Depression. Stay-home moms were 60% more likely to have been sad or depressed.

Gallup also asked about positive feelings (Thriving, Smiling or Laughing, Learning, Happiness, Enjoyment), and while the differences were smaller, they went the same way, with stay-at-home moms on the shorter end. Still it’s encouraging that 86% of them had Experienced Happiness 86%; so had 91% of the employed moms.

Money matters. As Rosen said,

This isn’t about whether Ann Romney or I or other women of some means can afford to make a choice to stay home and raise kids. Most women in America, let’s face it, don’t have that choice.

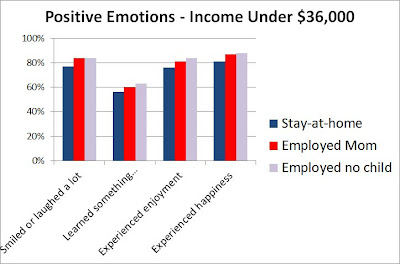

Gallup found a small interaction effect. The stay-at-home mom-employed difference was greater for low-income women.

The Gallup poll does not offer much speculation about why stay-at-home moms have more sadness and less happiness. One in four experienced “a lot” of depression yesterday. That number should be cause for concern.

Maybe women feel more uncertain and less able to control their lives when they depend on a man, especially one whose income is inadequate. Maybe stay-at-home moms find themselves more isolated from other adults. Maybe they are at home not by choice but because they cannot find a decent-paying job. Or maybe money talks, and what it says to unpaid stay-at-home moms is society does not value your work. Nor, in comparison with other wealthy countries, does US society or government provide much non-financial support to make motherhood easier.

The late Donna Summer sang,

She works hard for the money

So you better treat her right

But how right are we treating women who work hard for no money?

——————————-

* For example, Edward Conrad is a former partner of Romney. In a recent article in the Times Magazine, Adam Davidson writes, “If a Wall Street trader or a corporate chief executive is filthy rich, Conrad says that the merciless process of economic selection has assured that they have somehow benefitted society.”

** Hillary Clinton committed a similar gaffe twenty years ago in response to a reporter’s question about work and family “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was to fulfill my profession which I entered before my husband was in public life”