Iceland continues to experiment with new ways to promote majority living standards. According to the Icelandic Grapevine, a bill has been submitted to the Icelandic parliament that would shorten the workweek. More specifically, it would change the definition of a full time workweek to 35 hours instead of the current 40 and the full workday to 7 hours rather than the current 8.

As the Grapevine reports:

The bill points out that other countries which have shorter full time work weeks, such as Denmark, Spain, Belgium, Holland and Norway, actually experience higher levels of productivity. At the same time, Iceland ranked poorly in a recent OECD report on the balance between work and rest, with Iceland coming out in 27th place out of 36 countries.

The bill also points out that a recent Swedish initiative to shorten the full time work day to six hours has been going well, with some Icelanders calling for the idea to be taken up here. In addition, the bill also cites gender studies expert Thomas Brorsen Smidt’s proposal to shorten it even further, to four hours.

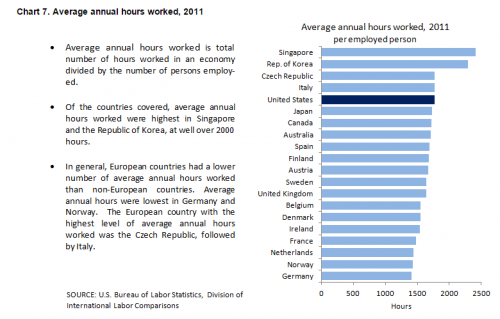

There is certainly significant variation among countries in the length of the workweek, as the following information from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows:

In 2011 the average annual hours worked per employed person in the U.S. was 1758. The number for French workers was 1476. It was 1411 for German workers. Assuming a 40 hour workweek, the average U.S. worker had a work year more than two months longer than the average German worker. It is also worth noting that while all the countries that reported data for the entire period 1979 to 2011 showed reductions in work time, the reduction was the smallest in the U.S.

Although it is not easy to establish a clear relationship between work hours and productivity, there is reason to believe that the relationship may be inverse. In other words, the shorter the workweek the more productive we are. It would certainly be nice, for many reasons, if someone in the U.S. Congress followed the lead of Iceland and introduced a bill to reduce work time in the U.S.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.