Flashback Friday.

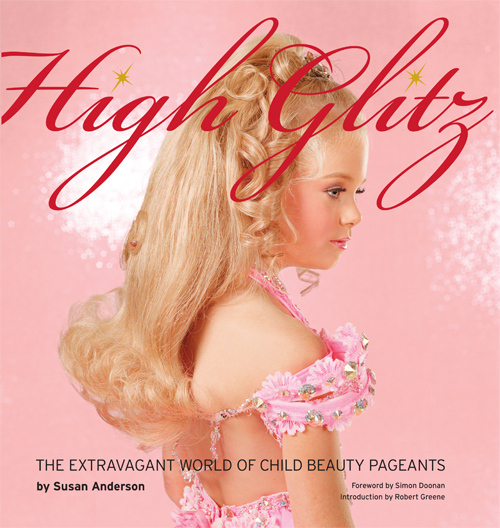

I just have to say “wow” to this ad for Quartz counter tops, sent it by Lisa Ray of Parents for Ethical Marketing and Corporate Babysitter:

The ad depicts a little girl fantasizing about growing up, but growing up means (extremely) high patent leather pumps; growing up means sexualizing herself.

And the ad does sexualize the little girl who, from the top-scanning-down, looks like a sweet girl trying on mommy’s shoes, but from the bottom-scanning-up, looks like an adult woman who suddenly transforms into a child. The white cotton dress implies innocence and purity, but it’s a costume we regularly see adult women wear when we want to both sexualize and infantilize them. In other words, this ad nicely plays into the mythology endorsed by pedophiles that even little girls want to feel sexy, even little girls want men’s attention, even little girls want sex.

And, yet, we are supposed to think this is sweet. The text, “Harmonizing Beautifully with Life” is, of course, ostensibly about the counter tops. But aligned with the image, it naturalizes both the girl’s fantasy and the conflation of female sex with the performance of sexualized femininity (it’s just “life”; as if there’s a gene for Christian Louboutin shoes that activates in the presence of double X chromosomes). More than simply naturalizing the girl’s fantasy of self-objectification, it endorses it (it’s beautiful harmony).

Notice also the class story in the ad. Who exactly is class privileged enough to have the freedom to allow “the quiet moments” to “steal the show”? Well, apparently people who are rich enough to wear Louboutin shoes. Louboutin began putting red soles on all his shoes as a not-so-subtle way to advertise that the shoe was Louboutin and, therefore, a very expensive shoe. It worked. Fashion writers started pointing out the red soles with glee, as in this story about Angeline Jolie on a red carpet. The fact that the sole of this shoe is red is no accident, it’s meant to add class to the counter tops, in both senses of the word.

A final word on race: That the girl in the ad is white is no accident. And it’s not only because marketers expect the majority of their customers to be white, but because of what whiteness represents. Her white skin symbolizes the same thing that the white counter tops and white dress symbolize: purity, cleanliness, even innocence. It is only because all those symbolic elements are there that we can put a black patent leather heel with a red sole on her and still think “sweet.” Imagine the same ad with a black child. In the U.S., black women are often stereotyped as sexually loose, morally corrupt, irresponsible teen mothers on welfare. With that symbolic baggage, this ad would be a morality lesson on the hypersexuality of black girls and their propensity to “grow up too fast.” It wouldn’t look sweet, it’d look dangerous.

“Harmonizing beautifully,” indeed.

Originally posted in 2010.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.