Cross-posted at Osocio.

We’ve been covering the saga of Russian protest punk group Pussy Riot for over a year now. The feminist collective performed guerrilla musical protests around Russia against Vladimir Putin. One in particular, in a church, ended with members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina sentenced to two years imprisonment for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred”. The human rights implications of this sentence attracted much worldwide attention, with Amnesty International and celebrities like Sting, Yoko Ono and Madonna speaking out for the women.

But something else happened. The “Free Pussy Riot” movement, with its iconic knitted balaclavas and provocative language, became a popular meme. The cause célèbre was even appropriated by the fashion industry.

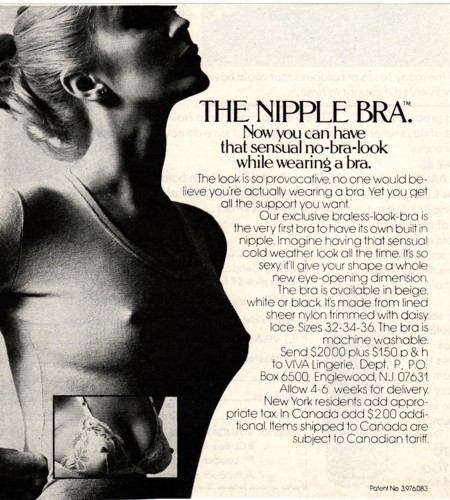

Which is what makes this video by Blush lingerie an intriguing conundrum. While it legitimately promotes the freepussyriot.org fundraising site to help the women, it is also promoting a product using a woman’s sexuality as the bait:

On the first anniversary of the Pussy Riot concert in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, the Berlin based Lingerie label blush supports the free pussy riot movement with a sexy protest march through icy Moscow (-15° C). Support Freepussyriot.org!

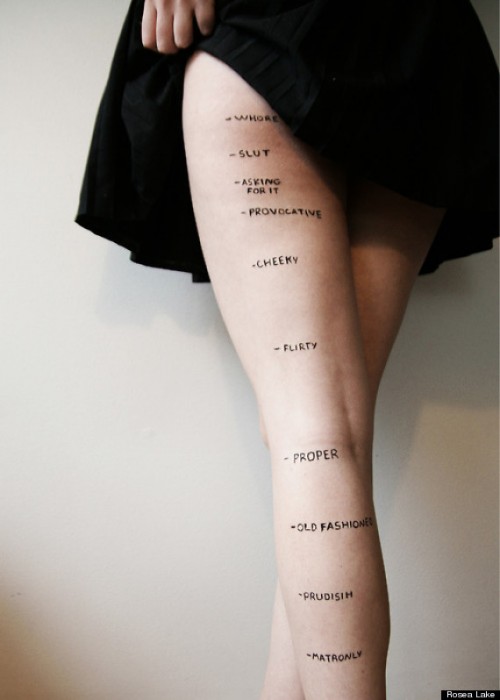

This is no Femen action, in which women’s bodies become weapons of protest. It is a commercial for sexy underwear that pays for its appropriation of a radical feminist cause by directing people to that cause.

Is this irony?

Tom Megginson is a Creative Director at Acart Communications, a Canadian Social Issues Marketing agency. He is a specialist in social marketing, cause marketing, and corporate social responsibility. You can follow Tom at workthatmatters.blogspot.com.