I’m on a plane right now, flying from Sacramento back to Albany. And sitting here I’m reminded of how air travel itself reflects the growing inequality of society in a trivial, but suggestive, way.

Planes have always had first-class and passenger cabins, at least as far as I know. If the Titanic had this distinction, I’m guessing it was in place from the beginning of commercial aviation.

But for most of my adult life, planes — at least the ones I usually fly on, from one U.S. city to another — looked something like this:

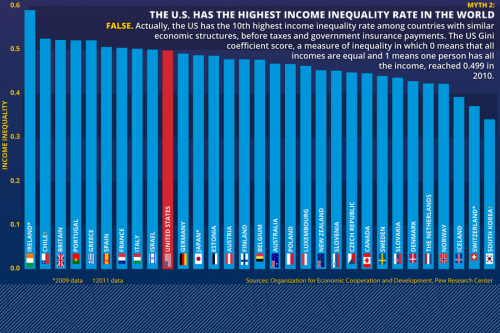

Just roughing it out here, this means that 7% of the passengers used about 15% of the room, with the other 93% using 85% of the cabin space. Such a plane would have a Gini index of about 8. The Gini index is measure of inequality, a fancy statistical way of representing inequality in the income distribution of a country’s population. For reference, the U.S. Gini is about 48, and the global one is around 65.

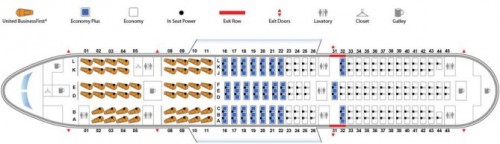

Domestic airlines have pretty much moved to a three-tier system now, in which the traditional first-class seating is supplemented by “Economy Plus,” in which you get an extra three or four inches of legroom over the standard “Economy” seats. I, as usual, am crammed into what should really be called “Sardine Class” — where seats now commonly provide a pitch of 31”, a few inches down from what most planes had a decade ago.

In today’s standard U.S. domestic configuration, the 12% of people in first class use about 25% of the passenger space, the 51 people in Economy Plus use another 30%, leaving the sardines — the other 157 people — with 45%. That gives us a Gini index of about 16.

Transatlantic flights, however, are increasingly taking this in-the-air distinction to new heights. Take, for example, the below United configuration of the Boeing 777. It boasts seats that turn into beds on which one can lie fully horizontal. United calls this new section of bed-seats “BusinessFirst.”

Unsurprisingly, though, these air-beds take up even more space than a nice comfy first class seat. So if we look again at how the space is distributed, we now have 19% of the people using about 35% of the plane, 27% using another 25%, and the final 52% using the last 40%. The Gini index has now increased to 25.

It’s not often you see such a clear visual representation of our collective acceptance of the right of a small fraction of people to consume a very disproportionate percentage of resources. I wonder how much of the shift is actually driven by increased inequality, as opposed to improved capacity for price discrimination.

And it’s also worth noting that the plane above, while unequal relative to the old-fashioned three-rows-of-first-class-and-the-rest-economy layout, is still nowhere near the inequality of the U.S., or the world.

Elizabeth Popp Berman, PhD is an associate professor of sociology at the University at Albany. She is the author of Creating the Market University: How Academic Science Became an Economic Engine and regularly blogs at OrgTheory, where this post originally appeared.