Karl Marx argued that capitalist modes of production always involve the exploitation of the working class by the owning class. The owning class are the capitalists. They secure the means of production — the factories, tools, and machinery — and employ workers to use those resources to produce goods.

When these goods are sold, capitalists extract the surplus value. This isn’t an magical good that blinks into existence thanks to the Capital Fairy, it’s a concrete good derived directly from the exploitation of the working class. Surplus value only exists when workers are paid less than the value they added with their work. If they were paid as much as their work was worth, capitalists would break even. And that’s not what they have in mind.

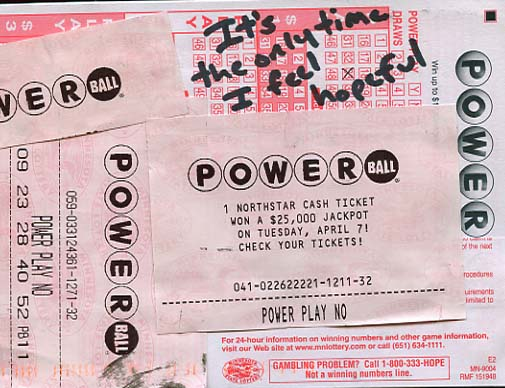

This comic at A Softer World illustrates this idea perfectly.

In other words, if capitalists paid workers what their work was actually worth, there wouldn’t be any profit left to skim off the top, leaving the rest of us with a value deficit.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.