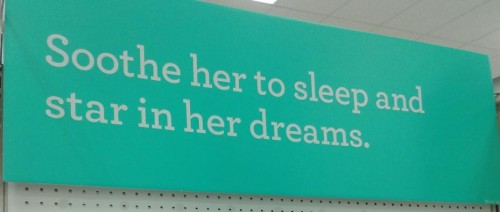

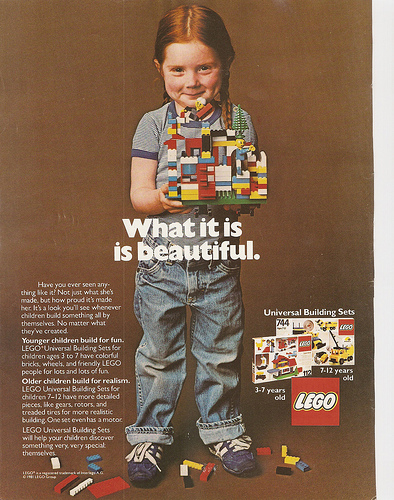

After the recent scandal over LEGO Friends, I am excited to report that I am in the process of working with a LEGO “fanatic,” David Pickett, on a series of posts about gender and the history of LEGO. In the meantime, as a teaser, I wanted to offer you two LEGO ads that were from the same campaign as the one making its semi-viral way around the internet (1980-1982). As with the original, these are evidence that advertising doesn’t have to reproduce the idea of “opposite sexes”:

Thanks to Moose Greebles and his Photostream.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.