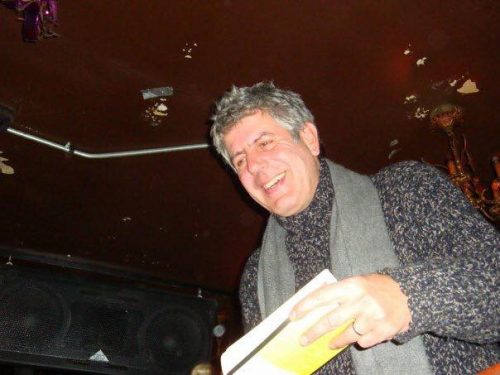

“There is a real danger of taking food too seriously. Food needs to be part of a bigger picture”

-Anthony Bourdain

As someone who writes about food, about its ability to offer a window into the daily lives and circumstances of people around the globe, Anthony Bourdain’s passing hit me particularly hard. If you haven’t seen them, his widely-acclaimed shows such as No Reservations and Parts Unknown were a kind of personal narrative meets travelogue meets food TV. They trailed the chef as he immersed himself in the culture of a place, sometimes one heavily touristed, sometimes more removed from the lives of most food media consumers, and showed us what people ate, at home, in the streets and in local restaurants. While much of food TV focuses on high end cuisine, Bourdain’s art was to show the craftsmanship behind the everyday foods of a place. He lovingly described the food’s preparation, the labor involved, and the joy people felt in coming together to consume it in a way that was palpable, even (or especially) when the foods themselves were unusual.

At their best, these shows taught us about the history and culture of particular places, and of the ways places have suffered through the ills of global capitalism and imperialism. His visit to the Congo was particularly memorable; While eating tiger fish wrapped in banana leaves, spear-caught and prepared by local fishermen, he delved into the colonial history and present-day violence that continue to devastate this natural-resource rich country. After visiting Cambodia he railed against Henry Kissinger and the American bombing campaign that killed over 250,000 people and gave rise, in part, to the murderous regime of the Khmer Rouge. In Jerusalem, he showed his lighter side, exploring the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through debates over who invented falafel. But in the same episode, he shared maqluba, “upside down” chicken and rice, with a family of Palestinian farmers in Gaza, and showed the basic humanity and dignity of a people living under occupation.

Bourdain’s shows embodies the basic premise of the sociology of food. Food is deeply personal and cultural. Over twenty-five years ago Anthony Winson called it the “intimate commodity” because it provides a link between our bodies, our cultures and the global political economies and ecologies that shape how and by whom food is cultivated, distributed and consumed. Bourdain’s show focuses on what food studies scholars call gastrodiplomacy, the potential for food to bring people together, helping us to understand and sympathize with one another’s circumstances. As a theory, it embodies the old saying that “the best way to our hearts is through our stomachs.” This theory has been embraced by nations like Thailand, which has an official policy promoting the creation of Thai restaurants in order to drive tourism and boost the country’s prestige. And the foods of Mexico have been declared World Heritage Cuisines by UNESCO, the same arm of the United Nations that marks world heritage sites. Less officially, we’ve seen a wave of efforts to promote the cuisines of refugees and migrants through restaurants, supper clubs and incubators like San Francisco’s La Cocina that help immigrant chefs launch food businesses.

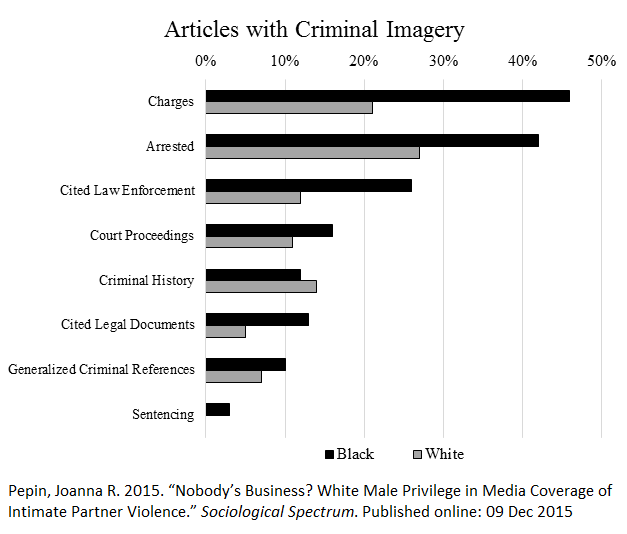

But food has often been and continues to be a site of violence as well. Since 1981 750,000 farms have gone out of business, resulting in widespread rural poverty and epidemic levels of suicide. Food system workers, from farms to processing plants to restaurants, are among the most poorly paid members of our society, and often rely on food assistance. The food industry is highly centralized. The few major players in each segment—think Wal-Mart for groceries or Tyson for chicken—exert tremendous power on suppliers, creating dire conditions for producers. Allegations of sexual assault pervade the food industry; there are numerous complaints against well-known chefs and a study from Human Rights Watch revealed that more than 80% of women farmworkers have experienced harassment or assault on the job, a situation so dire that these women refer to it as the “field of panties” because rape is so common. Racism is equally rampant, with people of color often confined to poorly-paid “back of the house” positions while whites make up the majority of high-end servers, sommeliers, and celebrity chefs.

More than any other celebrity chef, Bourdain understood that food is political, and used his platform to address current social issues. His outspoken support for immigrant workers throughout the food system, and for immigrants more generally, colored many of his recent columns. And as the former partner of Italian actress Asia Argento, one of the first women to publicly accuse Harvey Weinstein, Bourdain used his celebrity status to amplify the voice of the #metoo movement, a form of support that was beautifully incongruous with his hyper-masculine image. Here Bourdain embodied another of the fundamental ideas of the sociology of food, that understanding the food system is intricately interwoven with efforts to improve it.

Bourdain’s shows explored food in its social and political contexts, offering viewers a window into worlds that often seemed far removed. He encouraged us to eat one another’s cultural foods, and to understand the lives of those who prepared them. Through food, he urged us to develop our sociological imaginations, putting individual biographies in their social and historical contexts. And while he was never preachy, his legacy urges us to get involved in the confluence of food movements, ensuring that those who feed us are treated with dignity and fairness, and are protected from sexual harassment and assault.

The Black feminist poet Audre Lorde once wrote that “it is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.” Bourdain showed us that by learning the stories of one another’s foods, we can learn the histories and develop the empathy necessary to work for a better world.

Rest in Peace.

Alison Hope Alkon is associate professor of sociology and food studies at University of the Pacific. Check out her Ted talk, Food as Radical Empathy