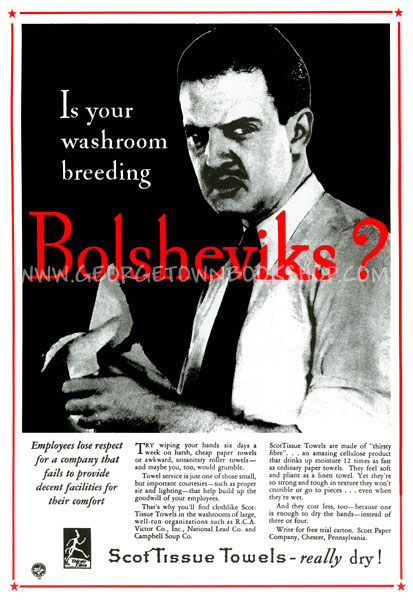

Yesterday, while recovering from the flu, I was glancing through Jon Stewart’s new book Earth: The Book. In the chapter on commerce they included a vintage Scot Tissue ad that I initially thought was a joke. Turns out it was real, first appearing in the 1930s and urging employers to stock bathrooms with Scot Tissue products to prevent turning their employees into radical communists:

(Image via.)

Text:

Employees lose respect for a company that fails to provide decent facilities for their comfort.

Try wiping your hands six days a week on harsh, cheap paper towels or awkward, unsanitary roller towels — and maybe you, too, would grumble. Towel service is just one of those small, but important courtesies — such as proper air and lighting — that help build up the goodwill of your employees. That’s why you’ll find clothlike Scot-Tissue Towels in the washrooms of large, well-run organizations such as R.C.A. Victor Co., Inc., National Lead Co. and Campbell Soup Co. ScotTissue Towels are made of “thirsty fiber”…an amazing cellulose product that drinks up moisture 12 times as fast as ordinary paper towels. They feel soft and pliant as a linen towel. Yet they’re so strong and tough in texture they won’t crumble or go to pieces…even when they’re wet. And they cost less, too — because one is enough to dry the hands — instead of three or four. Write for free trial carton. Scott Paper Company, Chester, Pennsylvania.

What I find fascinating is the idea that even minor discomforts might lead workers to become radicalized, and that one company would market to others based on the idea that they should respect their employees and keep them happy (at least in the way that serves Scot Tissue’s interests). Preventing the spread of communism isn’t, then, just about rooting out ideologues and rabble-rousers. The message is that becoming a Bolshevik may be a response to poor working conditions or treatment by management, and thus employers have a role to play in discouraging it by actually paying attention to potential causes of dissatisfaction and addressing them (in the bathroom, anyway), rather than simply a moral failing or outcome of ideological brain-washing.

UPDATE: Reader Ben has some interesting comments:

I’ve always wondered if it was meant to be serious. I understand that we live in an ironic age, but it’s not like ironic, self-mocking and humorous ads didn’t exist before the 1990s. As time passes and inside jokes lose their meaning, it gets harder and harder to correctly interpret texts with their original meaning and context intact.

Thoughts?