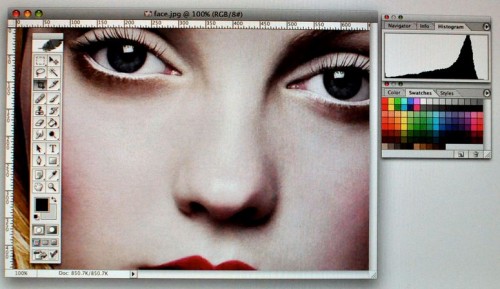

Writer and director Elena Rossini has released the first four minutes of The Illusionists. I’m really excited to see the rest. The documentary is a critique of a high standard of beauty but, unlike some that focus exclusively on the impacts of Western women, Rossini’s film looks as though it will do a great job of illustrating how Western capitalist impulses are increasingly bringing men, children, and the entire world into their destructive fold.

The first few minutes address globalization and Western white supremacy, specifically. As one interviewee says, the message that many members of non-Western societies receive is that you “join Western culture… by taking a Western body.” The body becomes a gendered, raced, national project — something that separates modern individuals from traditional ones — and corporations are all too ready to exploit these ideas.

Watch for yourself (subtitles available here):

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.