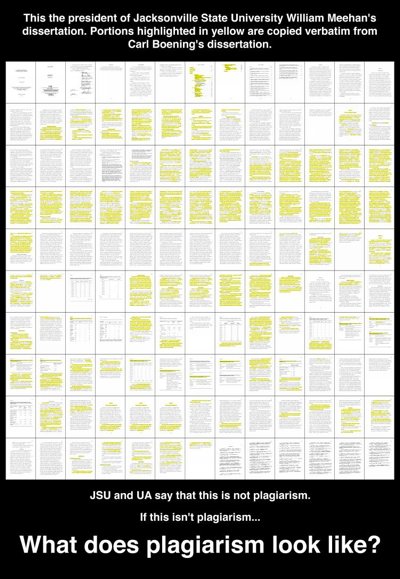

Nicole D. pointed out an interesting post on boingboing about plagiarism and status. Somehow or another someone noticed that large parts of the dissertation written by William Meehan, president of Jacksonville State University, were lifted word-for-word from an earlier dissertation by Carl Boehning; both men got their Ph.D.s from the University of Alabama. Here is an image indicating the extent of the copying–all the highlighted sections are exact replications of Boehning’s words (this does not include passages that were paraphrased without citation from his dissertation):

You can get a look at the actual documents if you’d like: Boening’s work, Meehan’s dissertation, and an index of the plagiarized sections.

Michael Leddy of Orange Crate Art says,

Neither the University of Alabama (which granted Boening and Meehan their doctorates) nor Jacksonville State University, where Meehan is president, has chosen to take up the obvious questions about plagiarism that Meehan’s dissertation presents. As another recent story suggests, plagiarism seems to be governed by a sliding scale, with consequences lessening as the wrongdoer’s status rises.

The “recent story” he mentions is about how a paragraph from Talking Points Memo ended up in a Maureen Dowd column, uncited and without quotation marks.

I find this beyond infuriating. I am, admittedly, hardcore about plagiarizing. I check every paper for it and I immediately give a 0 on any assignment where I find plagiarizing for a first offense; if it’s a second offense, I fail them in the course (I’d really prefer to fail them for the first offense, but we aren’t allowed to do that). I also turn in every instance to the college student ethics committee so the record will be on file. But, as Leddy says, apparently if you can rise high enough, then later discovery of your plagiarism–of the document on which a person’s entire Ph.D. is based, no less–won’t be held against you (though it did dim Joe Biden’s career for a while when he, or his writers, plagiarized part of a speech years ago).

Given that universities increasingly make statements about the importance of academic honesty, it’s an interesting position for JSU to be in–how do you tell your students they can’t plagiarize but admit that the president’s dissertation was largely copied? Perhaps they are using it as an illustration to students of how status, power, and privilege combine to protect some people more than others.