In recent years, sociologists have given attention to hookup culture and other modern forms of dating. Too often, however, this discussion ignores the experiences of trans people, and occasionally it focuses too narrowly on the college campus, ignoring the current prevalence of dating apps among many age groups.

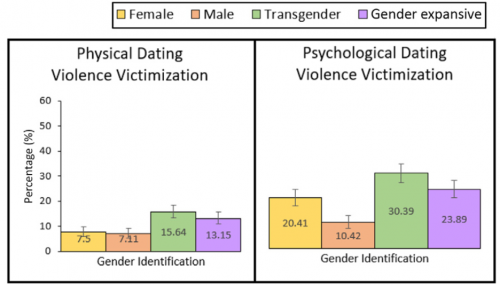

Focusing on trans experiences is especially important, as a 2021 study found that trans youth are twice as likely as cisgender women to have experienced physical dating violence, and fifty percent more likely to have experienced psychological dating violence. A 2023 study identified common experiences, most notably being fetishized and having to deal with others’ assumptions about trans people. “Because I’m a trans woman, people instantly assume that I must be this massive bottom,” said one participant. Another participant, a trans man, reported similar experiences, saying “I just felt like they weren’t talking to me. They were talking to an idea they had about me.”

Other research has looked at trans people’s decisions to disclose their trans identity to prospective partners on dating apps. Most participants proactively and explicitly disclosed their identity, citing concerns about violence. One participant, who was genderfluid and lived in a rural area, mentioned that when meeting someone face-to-face from a dating app, they always thought, “that person could be the person that kills me.” Others, however, will engage in softer disclosure methods, such as showcasing different facets of their identity on apps that allow multiple profile pictures.

Who is most vulnerable within the trans community? Another 2021 study found that BIPOC, queer, and transfeminine people are the most likely to have experienced dating violence. A 2022 study looked at the dating experiences of BIPOC trans women, finding their cis male partners would often conceal their relationship from the public. Consequences of this stigma included physical violence and psychological trauma. “We getting killed just because of the guys here were scared that they secret would come out,” said one woman. They also mentioned engaging in “survival strategies,” including hypervigilance, dressing to avoid being “found out,” and avoiding certain men.

The authors of these studies suggest several remedies to the problems they discussed. First is comprehensive trans-inclusive education, whether in the form of school curricula, sex education, or violence prevention training, which have been shown to make trans people and their partners more comfortable. Second, dating app users wanted better filtering options, with one person saying, “The majority of the interactions I have with cis men on dating apps are just shit, full stop . . . can I have less of them pop up?” Finally, some study authors recommended the prohibition of “trans panic defenses,” which allow perpetrators of violent crimes to justify their actions as a loss of control after learning their victim is transgender.

As trans people are reaching new levels of visibility and coming under fire in unprecedented ways, social science research shows us that it is important to look for ways to make for a safer and less anxious future for trans people as we look for romantic and sexual partners.

Leah Long is a history and sociology student at Macalester College who researches and writes about trans history and politics.