In 1922 the American Social Hygiene Association, funded by the American Public Health Service, created a social marketing campaign aimed at American teenagers. While it was predominantly about sexually transmitted infections, it also taught about good health and hygiene in general. And maintaining health, then as now, is not only about health but also about conforming to social norms–especially gender norms.

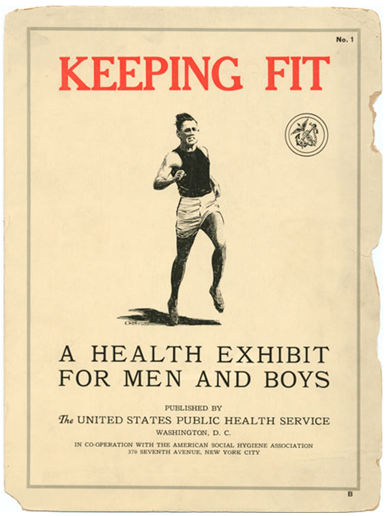

The posters aimed at boys were titled “Keeping Fit”:

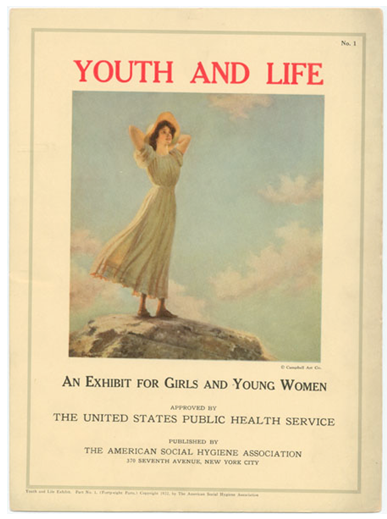

And the girls’ posters were titled “Youth and Life”:

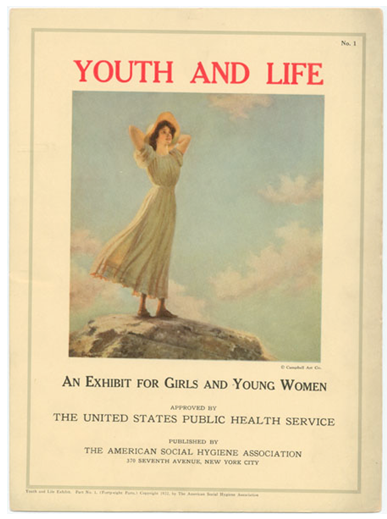

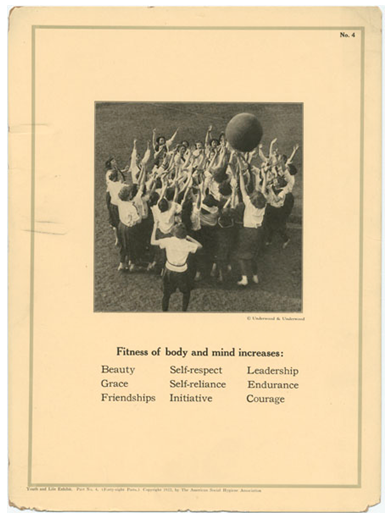

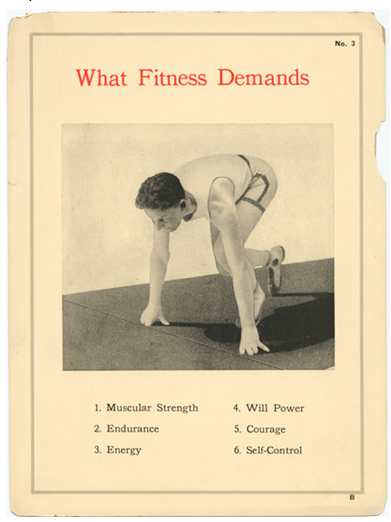

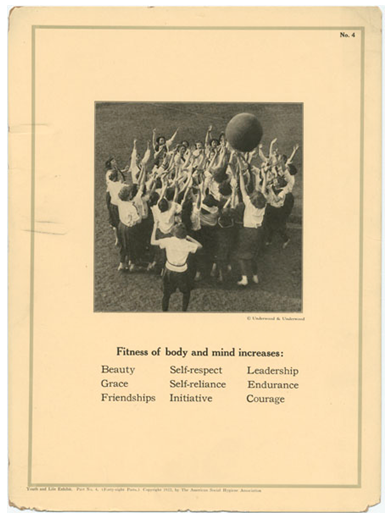

Comparing the boys and girls’ posters, you can see that fitness is not just about physical health; it is also about particular character traits. For boys, those traits are will power, courage, and self-control–traits that are based on a puritan work ethic that we value in a competitive capitalist society.

While courage and endurance were important for both boys and girls, fitness for girls was less about power and self-control, and more about grace, beauty, and friendship.

TEXT:

Paint your cheeks from the inside out. Outdoor exercise, baths, regular meals, and plenty of sleep will help. Most girls could be prettier than they are because most girls could be healthier.

TEXT:

Copy the pose but not the shoes. Correct posture gives attractive figure, straight back, freedom of action for heart and lungs, good muscle tone. Stand tall — chest up, not out — toes straight forward when walking or standing. A well-poised body develops self-respect, and wins the regard of others.

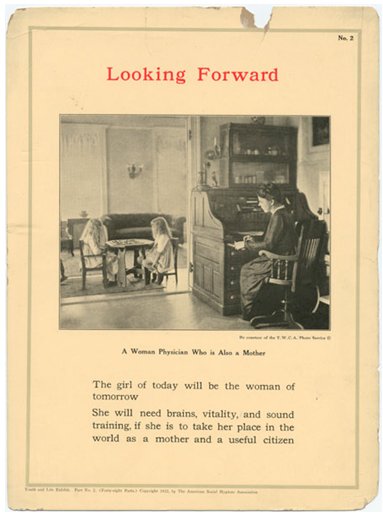

Men were taught how to grow up to be honorable husbands and fathers, while women were taught how to grow up to be good wives and mothers.

For boys:

TEXT:

The youth who achieves self-control can go joyfully and clean into marriage with the one girl he is willing to wait for, and become a husband and father without the danger of causing suffering to wife and child.

For girls:

TEXT:

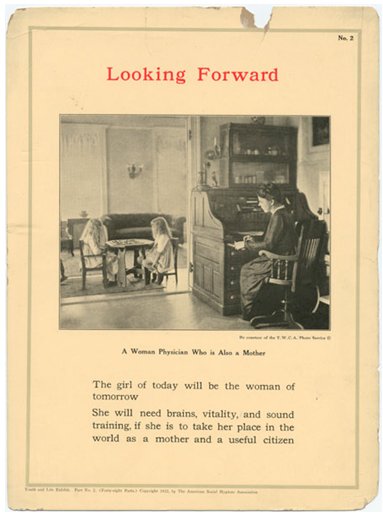

A woman physician who is also a mother. The girl of today will be the woman of tomorrow. She will need brains, vitality, and sound training, if she is to take her place in the world as a mother and a useful citizen.

It may be tempting to think that we know more now than we did back then and that with progress we make fewer mistakes today than they did in the past. However, controversy surrounding many health topics such as obesity, circumcision, and the way we screen, treat, and fundraise for breast cancer should tell you that we still have many assumptions behind our health recommendations that are based on ideology.

The posters are held at the Social Welfare History Archives at the University of Minnesota Libraries

——————————

Christina Barmon is a doctoral student at Georgia State University studying sociology and gerontology.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.