The start of the Fall semester has inspired me to re-post this fascinating phenomenon we covered last year.

—————————

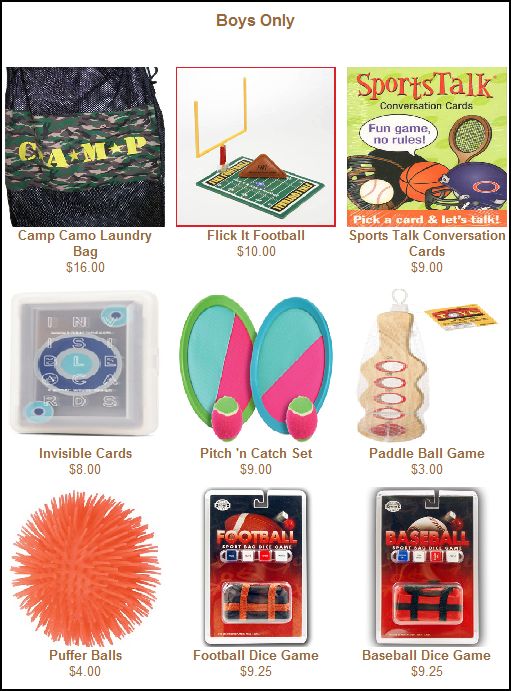

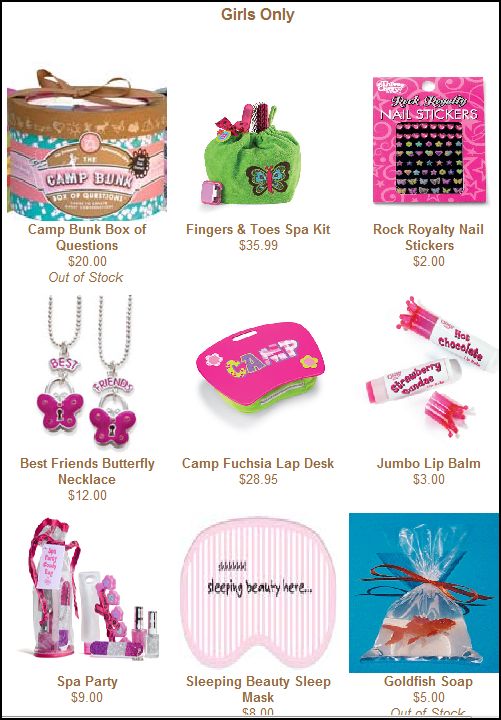

Rigby B. sent a link to the Just4Camp website to show us how care package products were gendered for “only” girls and boys. And, indeed, they were (screen shots below). But what is even more fascinating to me about this is the commodification of care.

The term “commodification” refers to the process by which something done for free becomes something done for money. Ever since the institutionalization of the wage, more and more things have become commodified. One particularly interesting category is care or what sociologists like to call “care work.”

Care work includes all of those tasks that involve nurturing and maintaining others: nursing, parenting, teaching, tending a home, etc. At one time in history, none of these things were paid jobs, but we have increasingly commodified them so that now paid nurses staff hospitals, home care workers take care of ailing elders, children spend the day in day care, professional teachers educate them, and housecleaners and gardeners can be paid to tend our homes and yards.

The care package is an example of care work. I still remember getting care packages in college with my favorite home made cookies and other things my parents thought I would like or needed. They take a lot of effort: thoughtfulness, shopping, baking, packaging, and mailing. And, here, we have an example of the commodification of that effort. The “care” in “care package” has been, well, outsourced.

Gendered care package ingredients:

For more on commodification, peruse our tag by that name.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.