olden days a glimpse of stocking

Was looked on as something shocking,

But now lord knows —

Anything goes.— Cole Porter, 1934

Poor Richard Cohen, columnist for the Washington Post. He’s being raked over the liberal coals for this recent observation:

Today’s GOP is not racist, as Harry Belafonte alleged about the tea party, but it is deeply troubled – about the expansion of government, about immigration, about secularism, about the mainstreaming of what used to be the avant-garde. People with conventional views must repress a gag reflex when considering the mayor-elect of New York – a white man married to a black woman and with two biracial children. (Should I mention that Bill de Blasio’s wife, Chirlane McCray, used to be a lesbian?) This family represents the cultural changes that have enveloped parts – but not all – of America. To cultural conservatives, this doesn’t look like their country at all.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates points out, gagging at a Black-White couple and their biracial children is, in fact, racist. So let’s focus on the word that Cohen uses to avoid that obvious conclusion – conventional.

Conventional: conforming or adhering to accepted standards; ordinary rather than different or original.

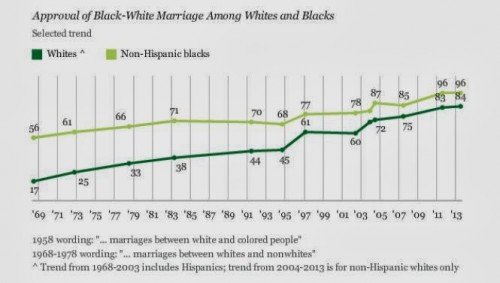

Matthew Yglesias at Slate seizes on that word and those “people with conventional views.” Yglesias too calls Cohen’s column “racist,” but more to the point, he provides some Gallup-poll evidence that interracial marriage is the new conventional.

Or as Cole Porter put it in a 1935 production:

When ladies fair who seek affection

Prefer gents of dark complexion

As Romeos —

Anything goes

Porter was bemused; Cohen is troubled. My spider sense tells me that if he’s not actually one of those people with conventional views repressing a gag reflex, he at least feels some strong sympathy for them. But they are on the wrong side of 21st century history, and not only on interracial marriage. Consider that parenthetical comment:

(Should I mention that Bill de Blasio’s wife, Chirlane McCray, used to be a lesbian?)

First, this is a pretty good example of one of my favorite rhetorical devices, paralipsis (or is it apophasis?) – saying something while saying that you’re not saying it. “To keep this discussion one of principle and not personalities, I won’t even mention that my opponent was arrested for wife-beating and has been linked to the Gambino crime family.”

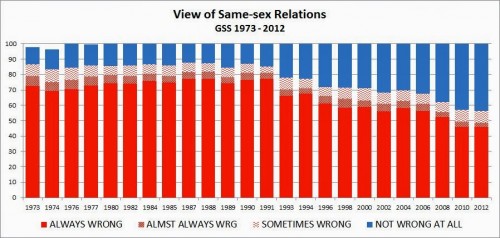

Second, as with interracial marriage, opinion on homosexuality has shifted considerably. Here’s the GSS data.

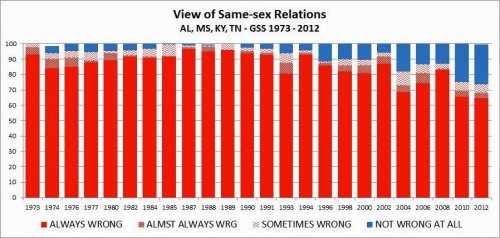

In less than twenty years, the Always Wrong delegation has shrunk from more than three-fourths to less than half. As Cohen says, this change has “enveloped” only parts of America. The gag reflex is still strong in the East South Central, which comprises Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky – the most unenveloped (unreconstructed?) of the GSS regions.

Despite the recent liberalizing trend, the Always Wrongs outnumber the Never Wrongs by more than two to one.

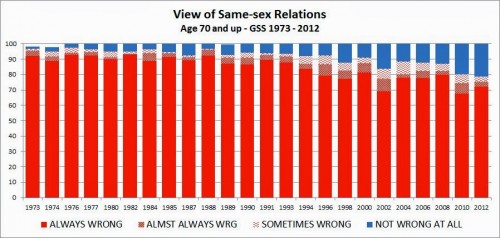

But wait, Cohen is not from the South or Appalachia. Like Bill deBlasio, he’s a New Yorker born and bred. (DeBlasio is from Manhattan, Cohen from Far Rockaway, Queens.) But there might be one other demographic source of that gag reflex – age. Cohen is 72. Here’s how his peers feel about people who share Cole Porter’s sexual orientation.

Among septuagenarians and their elders, those gagging at gays have a large 3½-to-1 edge.

Cohen is probably making the mistake that many of us make – projecting our own views as more widely held than they actually are. Journalists may be especially prone to this kind of projection, preferring to write about what “the public” or “the voters” want or think, when simple first-person statements would be more accurate. So when Cohen says, “to cultural conservatives, this doesn’t look like their country at all,” he may be talking about himself and the country he grew up in — Far Rockaway in the forties and fifties. But in 2013, that Far Rockaway is far away.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.