In a previous post, Lisa referred to Peggy McIntosh’s famous essay on White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. One of the many privileges that McIntosh identifies is that, as she writes, “I can turn on the television or open to the front page of the paper and see people of my race widely represented.”

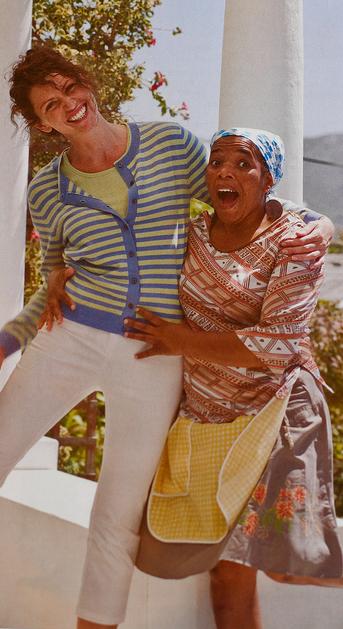

This statement resounded when I saw the images below from a 2011 Scottish Woolovers catalogue. Further, I was reminded that it’s not only a matter of whether we see people of our race widely represented, but also of how the media makes these portrayals.

The white woman in this ad is modelling a cardigan sweater. Meanwhile, the woman of colour in the photo is…well, that’s an interesting question. Nothing that she is wearing is for sale; she’s just there, wearing clothing that has no relevance to the advertisement.

Normally, you’d expect that a woman in a fashion catalogue would be there to model clothing, but in this case, the woman of colour doesn’t have such a role. She is a prop for the white model, there to frolic and help illustrate the benevolent and fun-loving nature of the fashionable white model, clad in an apron that marks her as potentially a servant of some kind. She’s not there to directly market clothes to a white target market.

SocImages has addressed other examples of privileged representations of white women in catalogues; a discussion of a Punjammies catalogue highlighted the exclusive reliance on white women as models, while portraying women of colour as labourers and beneficiaries of the good will of the white, female target market. In a similar vein, we also had a post illustrating a comparable trend in the representation (and lack thereof) of people of colour in films. It is a function of our unearned privilege that, when those of us in a privileged position come across racialized images and representations like these, it is all too easy to miss or ignore their problematic nature.

Thanks to Flickr user Wishiwerebaking for sending us these images.

—————

Hayley Price has a background in sociology, international development studies, and education. She recently completed her Masters degree in Sociology and Equity Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.