We celebrate education as the answer to almost all our economic problems. At the same time we largely ignore the enormous debt students are forced to acquire gaining a college degree and the great difficulties they face in landing a job that makes it possible for them to pay off that debt.

The Student Debt Problem

Student debt, as the Bloomberg Businessweek figure below highlights, is big and fast growing.

As the figure shows, the share of Americans that have graduated college has steadily grown to a current high of 32%. And, student debt has exploded. It now stands at approximately $1 trillion, significantly higher than credit card debt and home equity loans (which are loans secured by a second mortgage). Student debt is now second only to housing debt.

And, as Businessweek also points out, the share of young graduates suffering from debt is also on the rise. In 2003, only 25% of 25 year old graduates had student loans. In 2012, it was 43%. Moreover, “Over half of all student debt is held by households whose net worth is under $8500.”

The Employment Problem

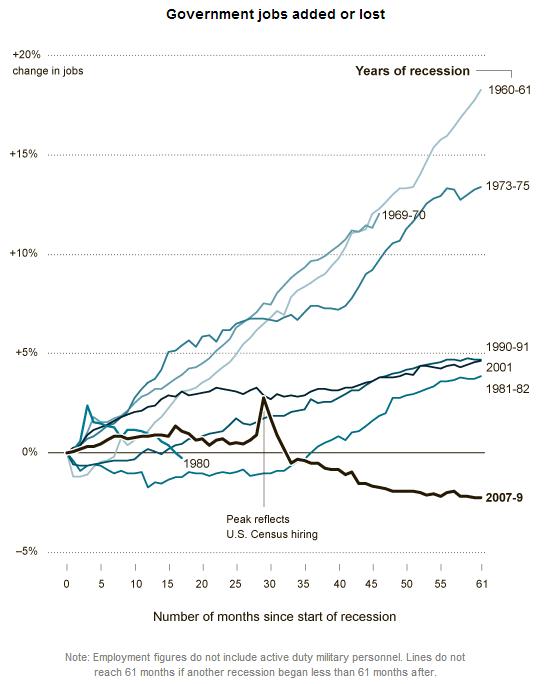

Of course, debt is only one side of the problem. Lack of good employment is the other. As an Economic Policy Institute (EPI) report explains:

The Great Recession that began in December 2007 was so long and severe, and the government response so inadequate, that the crater it left in the labor market continues to be devastating for workers of all ages. . . . The weak labor market has been, and continues to be, very tough on young workers: At 16.2%, the March 2013 unemployment rate of workers under age 25 was slightly over twice as high as the national average. Though the labor market is now headed in the right direction, it is improving very slowly, and the prospects for young high school and college graduates remain dim.

The figure below, taken from the EPI report, highlights just how bad the labor market is for recent college graduates. It shows that the underemployment rate for college graduates that are 21-24 years old and not pursuing additional education is still over 18%.

The underemployment measure used includes those officially listed as unemployed as well as those “that either have a job but cannot attain the hours they need, or want a job but have given up looking for work.” This measure does not “include ‘skills/education–based’ underemployment (e.g., the young college graduate working as a barista).” The report cites one study that estimates that in 2000, 40% of employed college graduates under the age of 25 worked at jobs that did not require a college degree. That rose to 47% in 2007 and 53% in 2012.

The table above, also from the EPI report, gives some sense of the wage pressure that young college graduates face. It shows that their real hourly wages have significantly declined since 2000.

The Economic Consequences

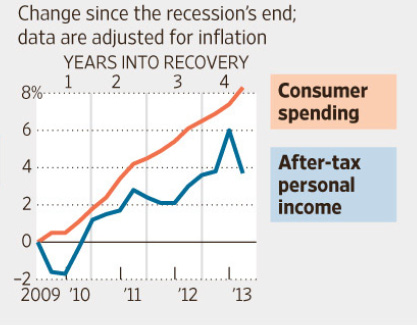

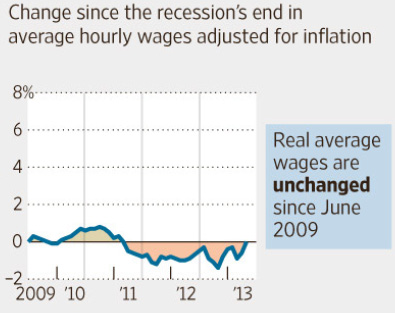

If you think rising debt and poor employment opportunities cannot end well for graduates and the economy, you are right. A post from the Naked Capitalism blog makes that clear:

Now that student loans are undeniably in bubble territory, the officialdom is starting to wake up and take notice. Evidence that students were taking on so much debt as a group that it was undermining their ability to be Good American Consumers wasn’t enough. . . .Student debt is senior to all other consumer debt; unlike, say, credit card balances, Social Security payments can be garnished to pay delinquencies. As a result, it has contributed to the fall in the home ownership rate, since many young people who want to buy a house can’t because their level of student debt prevents them from getting a mortgage.

Student loan delinquencies are getting into nosebleed territory. The Wall Street Journal, citing New York Fed data, tells us that student debt outstanding increased 4.6% in the last quarter [third quarter 2012]. Repeat: in the last quarter. Annualized, that’s a 19.7% rate of increase during a period when other consumer borrowings were on the decline. And this growth is taking place while borrower distress is becoming acute. 11% of the loans were 90+ days delinquent, up from 8.9% at the close of last quarter. The underlying credit picture is certain to be worse, since many borrowers aren’t even required to service loans (as in they are still in school or have gotten a postponement, which is available to the unemployed for a short period). And it was the only type of consumer debt to show rising delinquency rates.

This is the new subprime: escalating borrowing taking place as loan quality is lousy and getting worse.

The following chart, from the Wall Street Journal, illustrates the trends noted above.

If the situation wasn’t serious enough, because of a lack of Congressional action, the interest rate on new, subsidized Stafford loans—the loans that the federal government gives to college and university students with financial need—doubled on July 1, from 3.4% to 6.8%. These loans account for more than a quarter of all new federal student loans.

It sure seems like we need to stop stressing individualistic solutions to our economic problems and start talking about making broader structural changes to our economic system.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.