I’m in Salon today responding to the “men’s rights activists” who spammed Occidental College’s anonymous sexual assault reporting form this week. I, um, compare them to myself as a child:

I thought I failed fourth grade. It’s funny now that I’m a tenured professor at an elite college, but it wasn’t funny then. I lived a 45 minute walk from school and I ran home that day, tears in my eyes, clutching my unopened report card in my fist. I don’t remember much from my childhood, but I remember sitting on my front stoop and opening that horrible envelope. All Es for “excellent.” Huh.

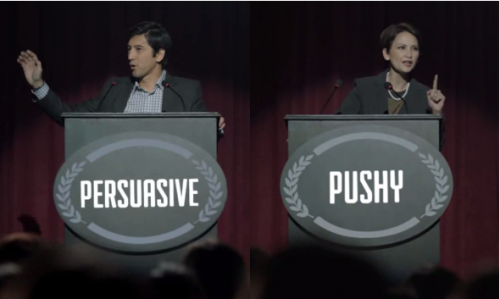

Looking back I realize that my sense that I’d failed was based on how my teacher treated me. She was the first adult who didn’t talk to me in a baby voice like I was the most specialest little girl in the whole world. She treated me like a small adult instead of kissing my ass. But it was terrifying because my ass had been kissed by everyone around me my whole life and, when I was demoted to “regular person” without any special privileges, it felt terrible and unfair. I was being persecuted.

See how special I was? I’m the one with the inflated sense of self.

The men attacking Occidental’s survivors are feeling something similar to me in fourth grade. They’re angry that “women are being listened to… They’re mad because they’re not the only ones that matter anymore.” They’re no longer being treated like they’re the most specialest little girl in the whole world.

It hurts when privileges are taken away, no matter how unearned. But that doesn’t make it okay to be an asshole. Just sayin’.

PS – Thanks Ms. Singh!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.