I once heard a transgender woman give a talk about the process of socially transitioning to being recognized as a woman. She discussed various decisions she made in taking some final critical steps toward the social identity of woman. She talked at length about her hair. She asked, “What kind of woman am I and how is my haircut going to indicate that?” She talked about being preoccupied with her hair for a long time as she attempted to figure out a cut and style that “felt right.” But what struck me the most was her discussion of carrying a purse.

She said that getting used to carrying a purse everywhere was one of the more challenging elements of the transition. If asked what I thought would be a significant everyday challenge if I were a woman, I don’t think purse would have been high on my list. But, it was high on hers. She discussed remembering to bring it, how to carry it, norms surrounding purse protection in public, but also more intimate details like: what belongs in a purse?

Purses and wallets are gendered spaces. There’s nothing inherent in men’s and women’s constitutions that naturally recommends carrying money and belongings in different containers. Like the use of urinals in men’s restrooms, wallets and purses are a way of producing understandings of gender difference rather than as a natural consequence of differences.

I got the idea for this post after reading Christena Nippert-Eng’s book, Islands of Privacy — a sociological study of privacy in everyday life. One chapter deals specifically with wallets and purses. In it, Nippert-Eng discusses one way she interviewed her participants about privacy. She used participants’ wallets and purses as a means of getting them to think more critically about privacy. Participants were asked to empty the contents of their wallets and purses and to form two piles with the contents: “more private” and “more public.” As they sifted through the contents of their wallets and purses, they talked about why they carried what they carried as well as how and why they thought about it as public or private.

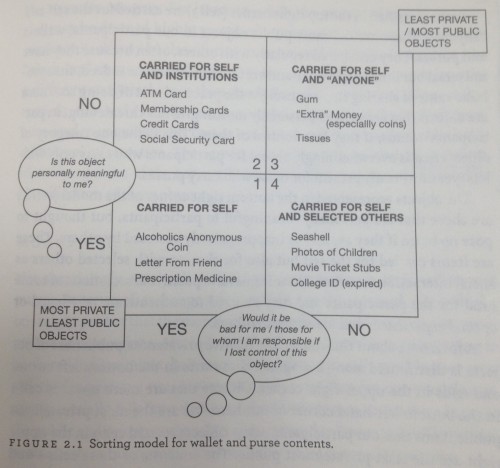

After collecting responses, she documented all of the contents and created categories and distinctions between objects based on how people thought about them as public or private. One question that was clearly related to privacy was whether the objects were personally meaningful to the participant. Invariably, objects defined as more personally meaningful were also considered more private.

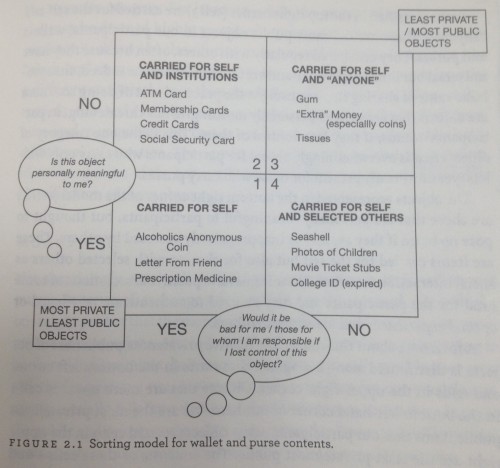

Another question that routinely arose as participants made sense of the objects they carry around everyday was how damaging it might be for participants if a specific object was taken. Based on this findings, she creates a useful table delineating participants concerns surrounding and understandings of the objects they carry with them (see left).

Just for clarification, there’s sort of a sliding scale of privacy going from most to least private as one proceeds from the bottom left cell to the top right cell. Thus, items classified by participants in the lower left cell (1) are the most private objects. Here, participants identified things like prescription medications, letters from friends, and a variety of personally meaningful objects that were thought of as completely private and carried only for the self.

Other items were still considered private, but “less private” than objects in cell 1 because they were shared selectively. Consider cell 2. While credit cards, bank cards, memberships, credit cards and money were all classified as “private,” individual’s also thought of them as “more public” than object in cell 1 because they were required to share these objects with institutions throughout their lives.

Similarly, some objects were thought of as “private,” but were also carried to share with certain others, such as photographs of children (cell 4). Finally, items classified in the top right cell (3) are the most public objects in wallets and purses—carried for the self and, potentially, “anyone” else. Items here include things like tissues, lip balm, money classified as “extra,” gum, breath mints, etc.

Objects from most of the cells exist in both wallets and purses, but not all of them. The contents of cell 3 (containing the “most public” objects in wallets and purses) are inequitably distributed between wallets and purses. As Nippert-Eng writes, “This is the one category of objects that is overwhelmingly absent for participants who carry only wallets, yet universally present for those who carry purses” (here: 130). She also found that some of her participants only carried objects all fitting the same cell in the above table. These participants — universally “wallet carriers” in her sample — carry only objects necessary for institutional transactions (cell 2).

This is, I believe, a wonderful analysis of one of the more subtle ways in which gender is accomplished in daily life. Certain objects are simply more likely to be carried in purses. Interestingly, this class of “feminine” objects are also objects that play a critical role in social interactions. Indeed, many of us are able to travel without these objects because we can “count on” purse-carriers as having them. Things like packs of gum, tissues, breath mints and more might seem like inconsequential objects. But, they play a crucial role in social interactions, and many of us count on purse-carriers to provide us with these objects when we are “in need.” It’s an aspect of care work by which some (those carrying purses) care for others (those without purses). And if they’re any good at it, the caring goes virtually unacknowledged, though potentially highly acknowledged when these objects are absent in purses. Children routinely ask their mothers for objects they presume they’ll be carrying in their purses. Indeed, these objects may be carried in anticipation of such requests. It’s a small aspect of doing gender, but a significant element of social interactions and life.

When I was learning about interviewing and ethnography, I was told to always carry a pack of gum, a pack of cigarettes (something “lite”), and a lighter. My professor told me, “It opens people up. It’s a small gesture that comforts people–puts them at ease.” These are the ways you might want people to feel if you’re asking them to “open up” for you. I still remember my first foray into “the field.” I bought my gum and cigarettes (objects I don’t typically carry) and the first thought I had was, “Where the heck am I going to keep these things?” What I didn’t realize at the time was that I was asking an intensely gendered question.

Tristan Bridges is a sociologist of gender and sexuality at the College at Brockport (SUNY). Dr. Bridges blogs about some of this research and more at Inequality by (Interior) Design. You can follow him on twitter @tristanbphd.