Not surprisingly, the new interactive chart Gendered Language in Teacher Reviews has been the subject of a lot of conversation among sociologists, especially those of us who study gender. For example, it reminded C.J. of an ongoing conversation she and a former Colorado College colleague repeatedly had about teaching evaluations. Comparing his evaluations to C.J.’s, he noted that students would criticize C.J. for the same teaching practices and behaviors that seemed to earn him praise: being tough, while caring about learning.

We’ve long known that student evaluations of teaching are biased. A recent experiment made headlines when Adam Driscoll and Andrea Hunt found that professors teaching online received dramatically different evaluation scores depending upon whether students thought the professor was a man or a woman; students rated male-identified instructors significantly higher than female identified instructors, regardless of the instructor’s actual gender.

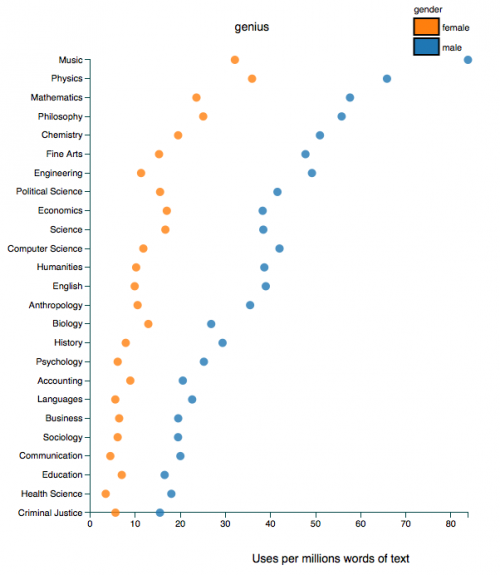

Schmidt’s interactive chart provides a bit more information about exactly what students are saying when evaluating their professors in gendered ways. Thus far, most commentaries have focused on the fact that men are more likely to be seen as “geniuses,” “brilliant,” and “funny,” while women, as C.J. discovered, are more likely to be seen as “bossy,” “mean,” “pushy.”

These discrepancies are important, but in this post, we’ve used the tool to shed light on some forms of gendered workplace inequality that have received less attention: (1) comments concerning physical appearance, (2) comments related to messiness and organization, and (3) comments related to emotional (as opposed to intellectual) work performed by professors.

Physical Appearance

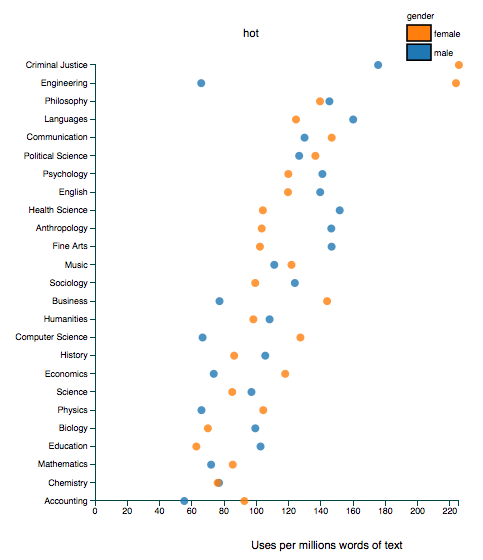

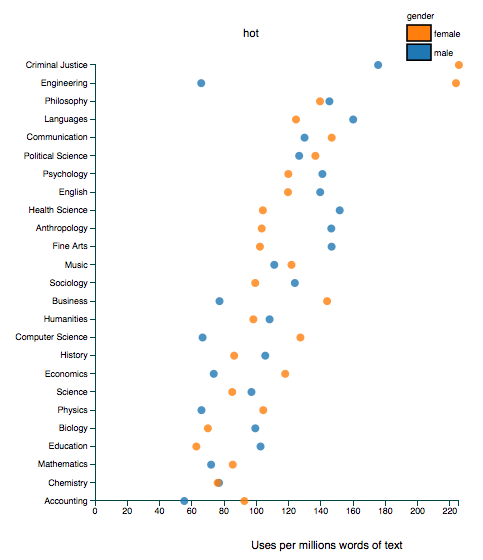

The results from Schmidt’s chart are not universally “bad” or “worse” for women. For instance, the results for students referring to professors as “hot” and “attractive” are actually mixed. Further, in some fields of study, women are more likely to receive “positive” appearance-based evaluations while, in other fields, men are more likely to receive these evaluations.

A closer examination, however, reveals an interesting pattern. Here is a list of the fields in which women are more likely to be referred to as “hot” or “attractive”: Criminal Justice, Engineering, Political Science, Business, Computer Science, Physics, Economics, and Accounting. And here is a list of fields in which men are more likely to receive these evaluations: Philosophy, English, Anthropology, Fine Arts, Languages, and Sociology.

Notice anything suspicious? Men are sexualized when they teach in fields culturally associated with “femininity” and women are sexualized when they teach in fields culturally associated with “masculinity.”

Part of this is certainly due to gender segregation in fields of study. There are simply more men in engineering and physics courses. Assuming most students are heterosexual, women teaching in these fields might be more likely to be objectified. Similarly, men teaching in female-dominated fields have a higher likelihood of being evaluated as “hot” because there are more women there to evaluate them. (For more on this, see Philip Cohen’s breakdown of gender segregation in college majors.)

Nonetheless, it is important to note that sexual objectification works differently when it’s aimed at men versus women. Women, but not men, are systematically sexualized in ways that work to symbolically undermine their authority. (This is why “mothers,” “mature,” “boss,” and “teacher” are among men’s top category searches on many online pornography sites.) And, women are more harshly criticized for failing to meet normative appearance expectations. Schmidt’s chart lends support to this interpretation as women professors are also almost universally more likely to be referred to as “ugly,” “hideous,” and “nasty.”

Level of (Dis)Organization

Christin and Kjerstin are beginning a new research project designed to evaluate whether students assess disorganized or “absent-minded” professors (e.g., messy offices, chalk on their clothing, disheveled appearances) differently depending on gender. Schmidt’s interactive chart foreshadows what they might find. Consider the following: women are more likely to be described as “unprepared,” “late,” and “scattered.” These are characteristics we teach little girls to avoid, while urging them to be prepared, organized, and neat. (Case in point: Karin Martin’s research on gender and bodies in preschool shows that boys’ bodies are less disciplined than girls’.)

In short, we hold men and women to different organizational and self-presentation standards. Consequently, women, but not men, are held accountable when they are perceived to be unprepared or messy. Emphasizing this greater scrutiny of women’s organization and professionalism is the finding that women are more likely than men to be described as either “professional” or “unprofessional,” and either “organized” or “disorganized.”

Emotional Labor

Finally, emotional (rather than intellectual) terms are used more often in women’s evaluations than men’s. Whether mean, kind, caring or rude, students are more likely to comment on these qualities when women are the ones doing the teaching. When women professors receive praise for being “caring,” “compassionate,” “nice,” and “understanding,” this is also a not-so-subtle way of telling them that they should exhibit these qualities. Thus, men may receive fewer comments related to this type of emotion work because students do not expect them to be doing it in the first place. But this emotional work isn’t just “more” work, it’s impossible work because of the competence/likeability tradeoff women face.

There are all sorts of things that are left out of this quick and dirty analysis (race, class, course topic, type of institution, etc.), but it does suggest we begin to question the ways teaching evaluations may systematically advantage some over others. Moreover, if certain groups—for instance, women and scholars of color (and female scholars of color)—are more likely to be in jobs at which teaching evaluations matter more for tenure and promotion, then unfair and biased evaluations may exacerbate inequality within the academy.

Cross-posted at Girl w/ Pen.