The United States imprisons more people than any other country. This is true whether you measure by percentage of the population or by sheer, raw numbers. If the phrase mass incarceration applies anywhere, it applies in the good ol’ U. S. of A.

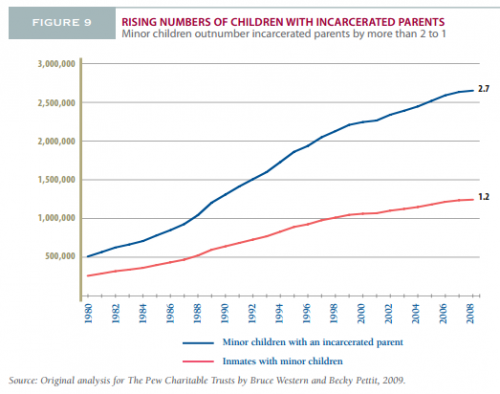

It wasn’t always this way. Rates of incarceration began rising as a result of President Reagan’s “war on drugs” in the ’80s (marijuana, for example), whereby the number of people imprisoned for non-violent crimes began climbing at an alarming rate. Today, about one-in-31 adults are in prison. his is a human rights crisis for the people that are incarcerated, but its impact also echoes through the job sector, communities, families, and the hearts of children. One-in-28 school-age children — 2.7 million — have a parent in prison.

In a new book, Children of the Prison Boom, sociologists Christopher Wildeman and Sara Wakefield describe the impact of parental imprisonment on children: an increase in poverty, homelessness, depression, anxiety, learning disorders, behavioral problems, and interpersonal aggression. Some argue that taking parents who have committed a crime out of the family might be good for children, but the data is in. It’s not.

Parental incarceration is now included in research on Adverse Childhood Experiences and it’s particular contours include shame and stigma alongside the trauma. It has become such a large problem that Sesame Street is incorporating in their Little Children, Big Challenges series and has a webpage devoted to the issue. Try not to cry as a cast member sings “you’re not alone” and children talk about what it feels like to have a parent in prison:

Wildeman and Wakefield, alongside another sociologist who researches the issue, Kristin Turney, are interviewed for a story about the problem at The Nation. They argue that even if we start to remedy mass incarceration — something we’re not doing — we will still have to deal with the consequences. They are, Wildeman and Wakefield say, “a lost generation now coming of age.”

The subtitle of their book, Mass Incarceration and the Future of Inequality, points to how that lost generation might exacerbate the already deep race and class differences in America. At The Nation, Katy Reckdahl writes:

One in four black children born in 1990 saw their father head off to prison before they turned 14… For white children of the same age, the risk is one in thirty. For black children whose fathers didn’t finish high school, the odds are even greater: more than 50 percent have dads who were locked up by the time they turned 14…

Even well-educated black families are disproportionately affected by the incarceration boom. Wakefield and Wildeman found that black children with college-educated fathers are twice as likely to see them incarcerated as the children of white high-school dropouts.

After the Emancipation Proclamation, Jim Crow hung like a weight around the shoulders of the parents of black and brown children. After Jim Crow, the GI Bill and residential redlining strangled their chances to build wealth that they could pass down. The mass incarceration boom is just another in a long history of state policies that target black and brown people — and their children — severely inhibiting their life chances.

Hat tip Citings and Sightings. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.