Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

I am a Londoner. A proud East Londoner, hailing from the working class. And this past week has been one of the most difficult I’ve encountered since I moved to the US nearly ten years ago. This weekend my hometown was attacked by rioters, just minutes away from my family’s homes and businesses, my high school and a million childhood and teenage memories. I don’t think I can do justice describing the feeling of watching this unfold from so far away. Needless to say, I wouldn’t wish the experience on anyone. Thankfully, it would appear that most of the violence has subsided. In its place: a myriad of social commentaries on why this happened. Not only from journalists, but from the everyman benefitting from the very same social media that helped rioters coordinate. Indeed, many sociologists have aired their ideas on Facebook, blogs and even op-eds.

But perhaps in our rush to explain and apportion blame perhaps we all missed asking some important questions. Why did we assume that the rioters are poor? How do we really know the class background of the rioters? Why did the media depict the rioters as underprivileged? And why did we accept this depiction unquestioningly?

The sociologist in me fantasizes of a post-riot 10 question survey to be distributed to all rioters immediately after completion of law breaking activities with questions including: what is your average household income, what is your and your parent’s highest level of education, what is your occupation, on a scale of one to ten just how angry with the government are you at this moment, ten being really jolly pissed off?

Short of such a research tool, how did we come up with generalizations of a group of people we really know little about, except for the fact that they all rioted?

As someone who has lived in both nations, I feel class is certainly a nuanced thing in Britain, much more so than in the US. But even with the subtleties of the British system you cannot simply see class. And for the most part, all the information we initially had about rioters is what we saw on TV and in still photographs.

We just cannot tell. If you thought you could tell, you’d be guessing, and you’d be basing your decision on ideas you have about the poor. Some might point to history; past rioters have tended to be from the working classes. But this only offers us the ability to make a prediction. But, most commentaries did not acknowledge that they were predicting who was involved. Some might argue that those wearing hoodies are poor, as the wearing of hoodies has become synonymous in the British press with certain low-income groups. But people of all class groups own hoodies. We also cannot surmise simply from a picture that the rioters were from the area they attacked and attempt to extrapolate social class from that location. Indeed, early police reports indicate that in some cases there was organized travelling to targeted areas and in my home borough of Waltham Forest, initial records show that more than half of those arrested did not live there. So how do we ascertain the social class of the rioters? Their behavior?

Did we see violence, looting and vandalism and assume that this could only be the work of poor people, and passively accepted the media’s categorization of the perpetrators as such? Or are we so blinded by our ideological beliefs, romanticizing the riots to be exactly what Marx warned us of that we bought this generalization? Or do we want so desperately to blame governmental cuts against the poor that we ignore the lack of solid evidence as to who these rioters really are? Or did we simply map on our understanding of other riots, and assume that all rioters are the same? I don’t have the answer to these questions, but think it is worth considering why we made the assumptions we did about the rioters when we had little to no data.

As I write this, on Friday 12th August, long after many of the commentaries have been published and opinions have been shared, news outlets are beginning to report the demographic information of the rioters who have appeared in court. (Go here and click on “Get the data”; sorry for the broken link earlier!)

Among those rioters who fit the stereotype — alienated, poor youth — are those who do not fit this type at all. They have already been the subject of several headlines: teachers, an Olympic ambassador, a graphic designer, college graduates and a “millionaire’s daughter.” The very fact that these “unusual suspects” have been singled out by the press demonstrates the power of this prejudice; we are shocked when it isn’t poor people rioting. But why? Is it because deep down we believe that the poor are capable of violence, but the rich aren’t? Or is it because this riot is more complex than simply the rage of downtrodden people?

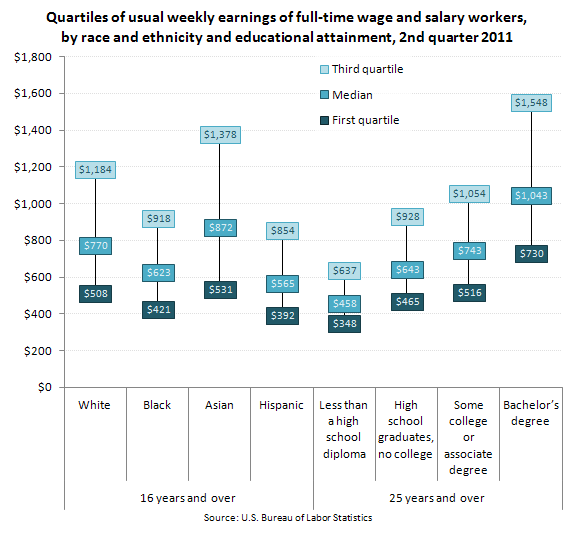

At this point, we are far from really knowing the class backgrounds of the rioters, especially since many people have not, and probably will not, be caught for their actions. We are still without reliable data to draw conclusions, just as we were earlier in the week when so many of us rushed to attribute this rioting to disenfranchised youth. I am not arguing that class won’t be an important factor in our understandings of these riots, and it may well be that these riots were mostly poor people. But my point is we cannot say with certainty at this moment in time that this is the case. And as an East End girl, I ask: what does it say about us, especially sociologists, that we were so willing to believe this about the poor without any solid data?

UPDATE: Kat provided a link to some data that wasn’t available when the post was being written. The Guardian mapped the home addresses of those arrested in the riots; the results indicate that they appear to have been disproportionately, though not solely, from areas that are poor — and getting poorer. Of those arrested, for instance, 41% came from the top 10% of areas when ranked by levels of deprivation.

Faye Allard is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Montclair State University. When not busy winning teaching awards, she is working on a book about the African American gender gap in high school educational achievement, called “Mind the Gap.”