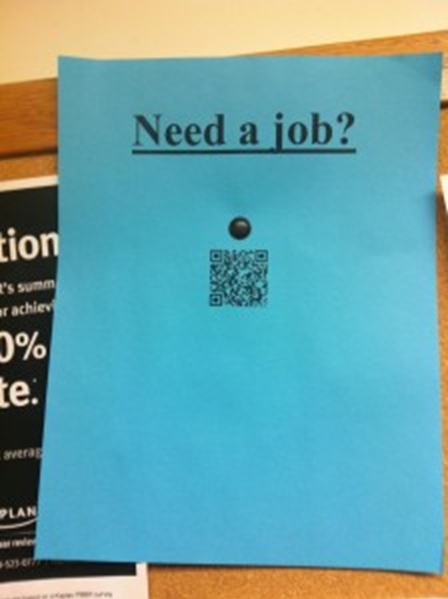

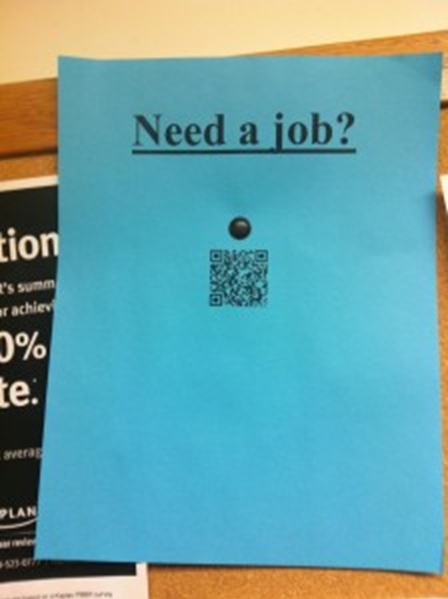

A QR, or Quick Response, code on a bulletin board of a college campus:

Steve Grimes shared this image and some interesting thoughts about how Quick Response codes, or QR codes, can contribute to inequality. That is, QR codes such as these serve to make certain content and information “exclusive” to those who have smartphones. He states,

There is a general thinking that technology can create a level playing field (an example of this is can be seen with the popular feelings about the internet). However, technology also has a great ability to create and widen gaps of inequality.

In a practical sense the company may be looking for students who are tech savvy. Using the matrix barcode may serve that purpose. However, the ad also shows how technology can exclude individuals; primarily in this case, students without smart phones. Ironically it is especially the students who need work (“need a job”) who may not have the money to afford a smart phone to read the ad.

Grimes’ thoughts are judicious, and reveal the inherent structural difficulties in alleviating inequality. QR codes are one form of “digital exclusivity,” the tendency of technology to re-entrench (mostly) class disparities in access to information. Though they may be able to access the information later when they have access to a computer, the person who has the smartphone is certainly living in a much more augmented world than the person without.

If we take as our assumption that access to information is a form of capital, than we can easily see how such technologies are implicated in the field of power. We can also see how digital exclusivity can contribute to the larger digital divide. In this sense, digital exclusivity, as a characteristic of particular technologies and forums (in this case as an access-point to particular forms of knowledge and information), contributes to larger inequalities of power and access to information in the digital age.

QR codes, though, may not be the best example of a digitally-exclusive technology. That is, QR codes have yet to serve as a common conduit of important information—access to such information has similarly meant little in terms of social or economic capital. It turns out that even most people with smartphones don’t know what they are or aren’t interested in using them. Grimes’ understandable frustration the digital divide, combined with the uneven usage of QR codes among mobile phone-using countries, leads us to believe that those black and white squares do more to instill a feeling of digital exclusivity than anything else.

—————————

David Paul Strohecker (@dpsFTW) is getting his PhD from the University of Maryland, College Park. He is currently doing work on the popularization of tattooing, a project on the revolutionary pedagogy of public sociology, and more theoretical work on zombie films as a vehicle for expressing social and cultural anxieties.

David A. Banks (@DA_Banks) is a M.S./Ph.D. student at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. His research interests include space, place, cyborgs, and networked bodies. He is currently working under the NSF’s GK-12 fellowship program, teaching science in urban school districts and developing new learning technologies. More at www.davidabanks.org.

Strokecker and Banks both blog at Cyborgology.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.