Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

It’s the kind of finding to warm the hearts of us liberal, Larry-Summers-hating, gender-egalitarians. Summers — you saw him in “The Social Network” as the Harvard president who had no patience for the Winklevoss twins (he didn’t have much patience for Cornell West either and probably many other things) — suggested that the dearth of women in top science and engineering positions was caused not so much by social forces as by innate sex differences in math ability (more here and many other places).

As others were quick to point out, those differences are greater in societies with greater gender inequality. That’s why the math gender gap in the U.S. has become much narrower over time. In societies with greater equality, like Sweden, Norway, and Israeli kibbutzim, the male-female gap in math disappears. But even in those societies, males still score higher on one type of mathematical skill: spatial reasoning.

I’m sure that evol-psych has some explanation for why male brains evolved to be more adept at spatial reasoning. I’m equally sure that those who favor social explanations can find residual sexism even in Sweden to explain spatial differences. That’s why a field experiment reported last summer is so interesting.

The research team (Moshe Hoffman and colleagues, pdf) tested people from two tribes in northern India — the Karbi and the Khasi. These had once been a single tribe but had split recently — a few hundred years ago. (Recent is a relative term, and we’re talking evolution here.) So they were similar economically (subsistence farming of rice) and genetically.

- The Karbi are patrilineal. Only the men own property, and they pass that property to their sons. Males get more education.

- Khasi society is matrilineal. Men turn their earnings over to their wives. Only women own property, which is passed along only to daughters. Males and females have similar levels of education.

Researchers went to four villages of each tribe, recruited subjects to solve this puzzle:

They offered an additional 20 rupees if the subject could solve the puzzle in 30 seconds or less.

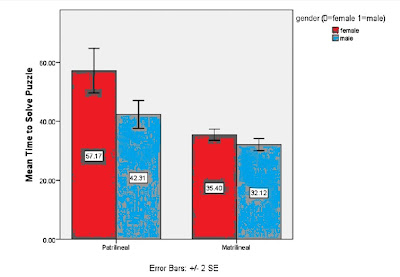

In the patrilineal society, women were much slower to solve the puzzle than were men. But among the matrilineal Khasi, the difference was negligible.

I’m not sure how much weight to give this one study, mostly because of sample size. Is the sample the 1300 villagers who worked the puzzle? Or is it 1 – one inter-tribal comparison? But the results are encouraging, at least for those who argue for greater gender equality.