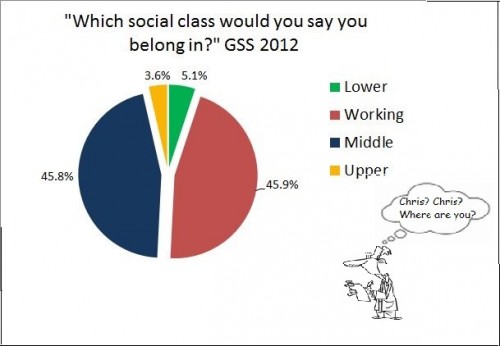

Chris Christie’s net worth (at least $4 million) is 50 times that of the average American. His household income of $700,000 (his wife works in the financial sector) is 13 times the national median. But he doesn’t think he’s rich.

I don’t consider myself a wealthy man. . . . and I don’t think most people think of me that way.

That’s what he told the Manchester Union-Leader on Monday when he was in New Hampshire running for president.

Of course, being out of touch with reality doesn’t automatically disqualify a politician from the Republican nomination, even at the presidential level, though misreading the perceptions of “most people” may be a liability.

But I think I know what Christie meant. He uses the term “wealth,” but what he probably has in mind is class. He says, “Listen, wealth is defined in a whole bunch of different ways . . . ” No, Chris. Wealth is measured one way – dollars. It’s social class that is defined in a whole bunch of different ways.

One of those ways, is self-perception.

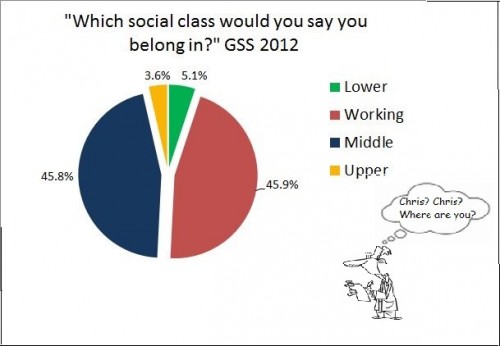

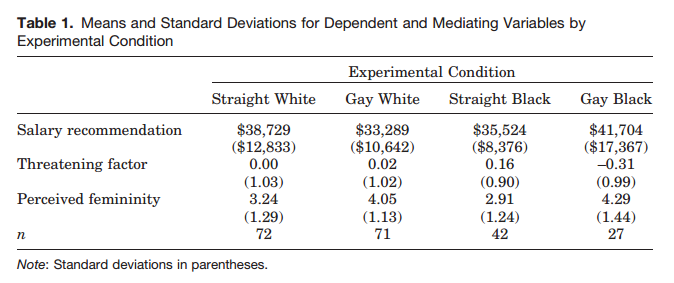

“If you were asked to use one of four names for your social class, which would you say you belong in: the lower class, the working class, the middle class, or the upper class?”

That question has been part of the General Social Survey since the start in 1972. It’s called “subjective social class.” It stands apart from any objective measures like income or education. If an impoverished person who never got beyond fifth grade says that he’s upper class, that’s what he is, at least on this variable. But he probably wouldn’t say that he’s upper class.

Neither would Chris Christie. But why not?

My guess is that he thinks of himself as “upper middle class,” and since that’s not one of the GSS choices, Christie would say “middle class.” (Or he’d tell the GSS interviewer where he could stick his lousy survey. The governor prides himself on his blunt and insulting responses to ordinary people who disagree with him.)

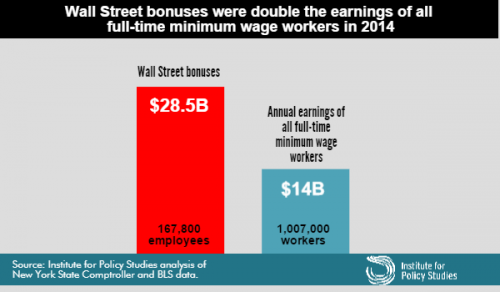

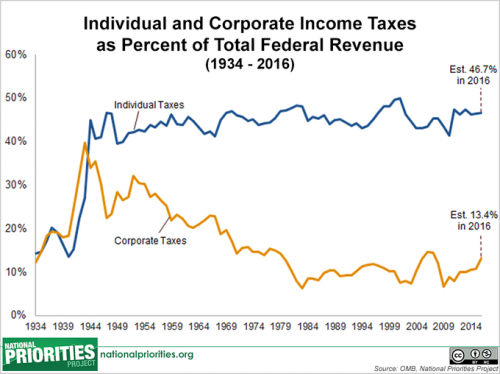

This self-perception as middle class rather than upper can result from “relative deprivation,” a term suggesting that how you think about yourself depends on who are comparing yourself with.* So while most people would not see the governor as “deprived,” Christie himself travels in grander circles. As he says, “My wife and I . . . are not wealthy by current standards.” The questions is “Which standards?” If the standards are those of the people whose private jets he flies on, the people he talks with in his pursuit of big campaign donations – the Koch brothers, Ken Langone (founder of Home Depot), Sheldon Adelson, Jerry Jones, hedge fund billionaires, et al. – if those are the people he had in mind when he said, “We don’t have nearly that much money,” he’s right. He’s closer in wealth to you and me and middle America than he is to them.

I also suspect that Christie is thinking of social class not so much as a matter of money as of values and lifestyle – one of that bunch of ways to define class. To be middle class is to be one of those solid Americans – the people who, in Bill Clinton’s phrase, go to work and pay the bills and raise the kids. Christie can see himself as one of those people. Here’s a fuller version of the quote I excerpted above.

Listen, wealth is defined in a whole bunch of different ways and in the end Mary Pat and I have worked really hard, we have done well over the course of our lives, but, you know, we have four children to raise and a lot of things to do.

He and his wife go to work; if they didn’t, their income would drop considerably. They raise the kids, probably in conventional ways rather than sloughing that job off on nannies and boarding schools as upper-class parents might do. And they pay the bills. Maybe they even feel a slight pinch from those bills. The $100,000 they’re shelling out for two kids in private universities may be a quarter of their disposable income, maybe more. They are living their lives by the standards of “middle-class morality.” Their tastes too are probably in line with those of mainstream America. As with income, the difference between the Christies and the average American is one of degree rather than kind. They prefer the same things; they just have a pricier version. Seats at a football game, albiet in the skyboxes, but still drinking a Coors Light. It’s hard to picture the governor demanding a glass of Haut Brion after a day of skiing on the slopes at Gstaad, chatting with (God forbid) Euorpeans.

Most sociological definitions of social class do not include values and lifestyle, relying on more easily measured variables like income, education, and occupation. But for many people, including the governor, morality and consumer preference may weigh heavily in perceptions and self-perceptions of social class.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.