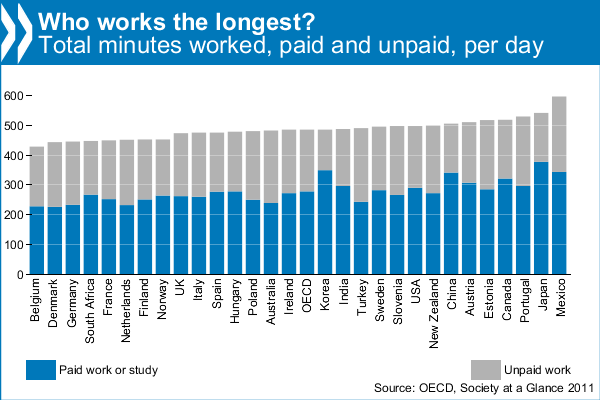

Dolores and Diego sent in a new study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The study measured time use in 30 countries, demonstrating significant differences in the amount of work and leisure enjoyed, on average.

The country reporting the fewest work hours was Belgium at just about 7 hours a day. The country reporting the most was Mexico; Mexicans reported working almost 10 hours per day. That’s enough hours to translate into 45.5 extra days a year that Mexicans work in excess of Belgians, and a month of extra work hours compared to the average country in this study (at 8 hours a day).

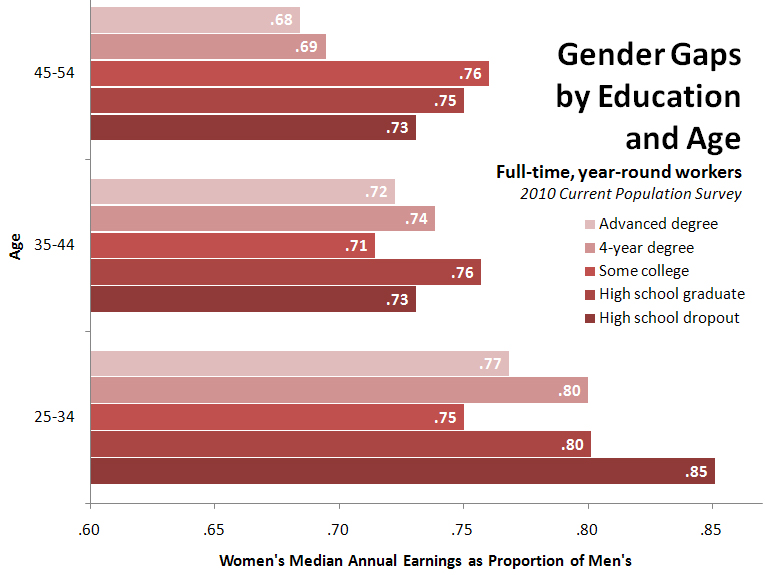

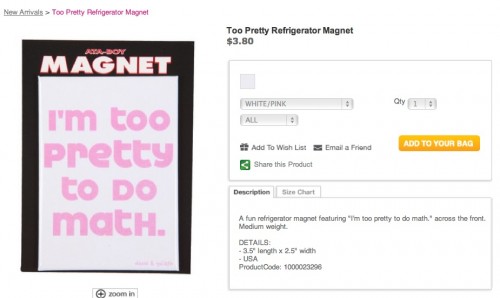

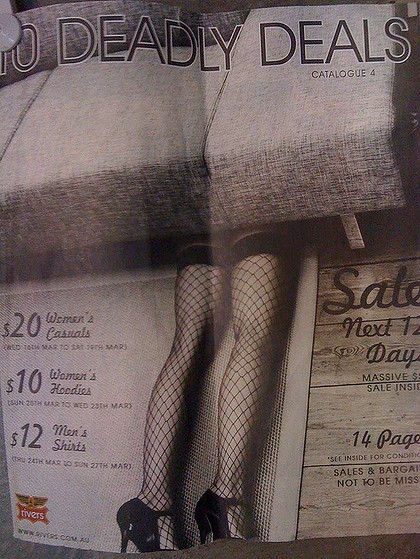

The OECD has also reported gender gaps in leisure across countries (Norway had the smallest gap in that study; Italy the largest) and we’ve seen the gender leisure gap reflected in American advertising.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.