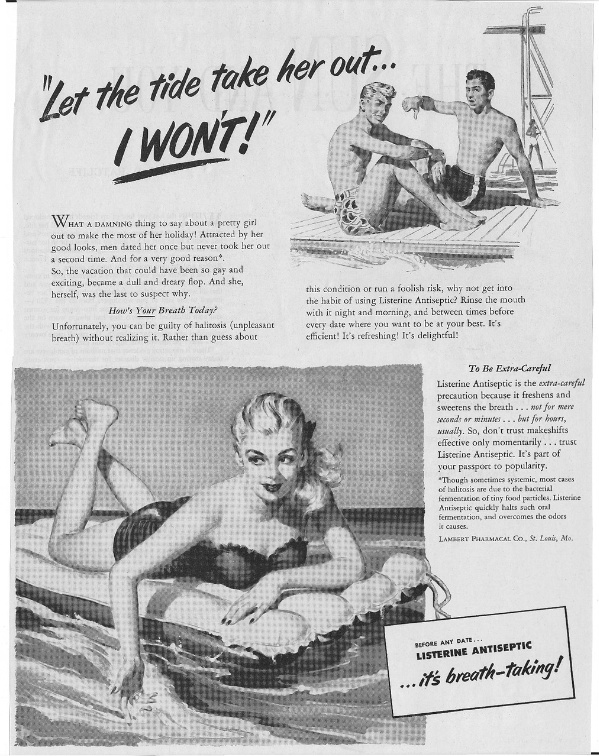

This ad, spotted by Stephanie DeH. in a physical therapist’s office, asks viewers to donate blood with the argument that it’s “easier” to save a life than to save the world:

Text:

Saving the world isn’t easy. Saving a life is.

Just one pint of blood can save up to three lives.

The ad commits two fallacies.

First, it compares saving the whole world (or maybe every tree in the world) with saving just “a” life. Saving a life may, indeed, be easier than saving the whole world, but it’s not a fair comparison. Saving the whole world is hard, but about as hard as saving every life on it.

Second, it suggests that we have to choose. “You could try to save the world,” the ad says, “but it’s pretty hopeless. It’s much easier to save a life. So put down that tree and donate blood.” Giving blood, then, is placed in competition with environmental activism as if (or because) volunteerism is a zero sum game.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.