The Making of a Backstage Sociologist

Originally given as an acceptance speech in 2004 when the Sociologists of Minnesota gave me the Distinguished Sociologist award.

PART I: THE EXISTENTIAL TRUTH OF LIVED EXPERIENCE

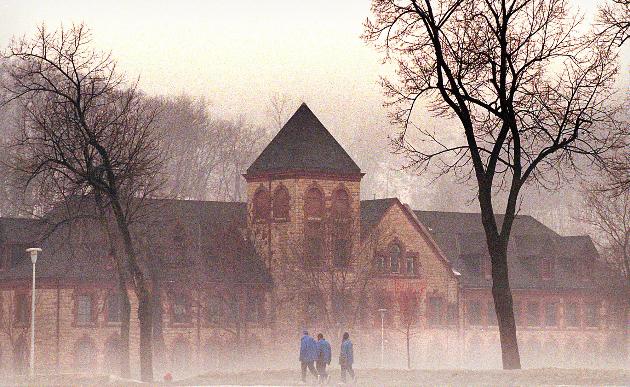

When young deviants set off on a series of picaresque adventures, they will be no stranger to synchronicity and serendipity. In 2004, two criminalists were co-presidents of Sociologists of Minnesota (SOM). Rather than pick the usual suspects for a conference like hotels or college campuses, they chose the Minnesota Correctional Facility—Red Wing, a juvenile prison. Simultaneously, an awards committee was busy selecting that year’s recipient of the Distinguished Sociologist award.

I was an idiosyncratic choice for the award. For all that, an eerie coincidence overshadowed savoring the award. In my acceptance speech, I came clean—I had once been an inmate there, behind what Bob Dylan once called the “Walls of Red Wing.” I had graduated high school and last walked out of that front gate 41 years before. The only word that seems to capture this strange turn of events is surreal.

Distinguished Sociologist . . . that title is both a tribute and fraught with ambiguity. The conferring of this award always leads some folks to question the appropriateness of the adjective: Was this person’s career truly distinguished? However, this may be the first time that the noun will generate as much controversy as the adjective. Who the hell died and made him a sociologist?

Despite persistent rumors to the contrary, everything in my curriculum vitae is true. Nevertheless, As Peter Berger puts it in Invitation to Sociology, “The first wisdom of sociology is this—things are not what they seem” (1963:23). To set the stage for my remarks, and to help make sense of this enigma, I will use one of Erving Goffman’s most enduring insights.

In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman distinguishes front stage from backstage. Most of us want to present an idealized self in our front stage performances. The backstage is where our show is “painstakingly constructed; it is here that illusions and impressions are openly constructed.” This backstage region is necessary because, according to Goffman, we must conceal from the audience certain “dirty work” that goes into creating the performance. These “vital secrets of the show” are what the audience would most likely find disconcerting or repugnant. An old adage neatly captured Goffman’s point: You do not want to know how sausage is made. (1959:112-113).

I am a sociologist. A PhD program did not bestow that identity upon me; no, I inhaled my sociological moxie the old-fashioned way—as a deviant, a dissident, and a grassroots organizer. I will probably never receive the American Sociological Association’s (ASA) seal of approval. In truth, I am a backstage sociologist. I would like to share with you, in the words of the Grateful Dead, “what a long, strange trip it’s been.” Come. Let me take you backstage. I want you to see the “dirty work” that went into the making of this sociologist

A Mennonite Homeboy

In less than 100 years and three generations, my family evolved from pious tillers of the soil into fallen-away urban nomads. I was born into a Mennonite colony, nice people but tight assed. An imposing patriarch, my grandfather used simple means to protect our traditional culture. In short, he was not one to spare the rod and spoil the child. However, even the most austere of Protestant ethics was not enough to save his youngest son. Alcohol, the auto, and World War II were too much for my father—he eventually left the Mennonites behind.

My parents were tenants on an 80-acre farm and semi-skilled laborers in Jackson, a small southwestern Minnesota town. My beloved colleague, Nancy Black, is fond of suggesting that wolves raised me. While this metaphor does vividly capture my take-no-prisoners personality, it is hardly fair to my parents. My mother and father made every effort to be good and dutiful parents. For these young, insecure newlyweds, the responsibilities of adulthood were challenge enough. Betty and Warren’s first offspring only added an irrepressible wild card to the mix. My natural insurgencies elicited a repertoire of unpredictable responses, ranging from indulgence to an iron fist. Trust has never been my strong suit.

This Mennonite homeboy was born under a bad sign; by age 4, the elders had expelled me from summer Bible school for fighting. I was a precocious child; by age 12, my story had become the town’s cautionary tale about juvenile delinquency. I was a case study of socialization gone array. At the time, those psychic wounds were disfiguring, forever etched in my mind. Only later did I discover the tenderness of wolves. Today, I can treat those memories with the detachment of a stand-up comic. In those days, however, my survival kit was limited to rage, violence and crime.

I first left my hometown at age 16 as a pariah, Lucifer’s apprentice. A nurturing aunt and uncle had persuaded my parents to let them take me in and try to detour my path to perdition. It only accelerated the pace. On Fridays, I would hitchhike home. Rides were unpredictable and once a driver dropped me off at a country crossroads, inhabited only by a ramshackle gas station. After waiting an hour for a ride, I wandered inside. Eventually the owner got a call. He said he had to run an errand and asked if I would watch the place. I begin pondering my wretched life. I climbed into the cab of the station’s gas truck. It was just one of a lifetime of rash decisions. I had been barreling along at 75 mph for about 30-35 miles when the flashing red lights of squad cars first appeared in the rear view mirror.

They transported me to the Jackson County jail. The next morning they marched me across the street to the courthouse. The town fathers had decided enough was enough. The judge sentenced me until the age 21 to what was commonly known as the “Red Wing Boys’ Reformatory.”

I had ambivalent feelings as I rolled across southern Minnesota, locked in the back seat of an unmarked squad car. On the one hand, I felt an existential despair that I only began to understand years later when I played the lead role in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. In Red Wing, I was always waiting, waiting for a deliverance that never arrived. On the other hand, I felt a sense of anticipation and exhilaration. From one end of the state to the other, bad-boy wannabes (like little Bobby Zimmerman from Hibbing) fantasized about making it to the big show. To understand that ambition, just listen to Dylan’s “Walls of Red Wing.”

I was in for a rude awakening. In those days, Red Wing was what Erving Goffman called a “total institution.” Privacy was an idea you checked at the front gate. You ate together, you worked together, you slept together, you showered together and, without benefit of stalls, you shit together. Back then, few adolescents faced trial as adults. Consequently, you rubbed shoulders on a daily basis with juvenile felons who may have been burglars, sex offenders, armed robbers or even murderers. In any sort of gulag, there are predators and there is prey. I spent my stint at Red Wing avoiding becoming anyone’s prey. When paroled, I had few remaining illusions. I just knew that I was not coming back.

But back I came. There were many “cottages” (the mother of all euphemisms) at Red Wing. Resembling medieval fortresses, those jagged stone buildings were gothic dungeons. The two that housed the most hardened boys and were the toughest places to do time were McKinley and Lincoln. This time, I drew Lincoln. I decided to live by Faulkner’s Nobel Prize motto — I would not merely endure: I would prevail. The highest status an inmate could achieve was to become a “belt” (in the old days, they literally wore belts across their chests and over their shoulders). Belts represented a combination of trustee and cottage enforcer. Two belts in each unit ran the show. Within a month, I had dispatched a cottage bully to the hospital infirmary. That made all the difference. I soon became the Lincoln belt.

Paroled once again after 10 months, I knew better than to return home. The good citizens of Jackson were just waiting to award me a scholarship to the “big house” at the Stillwater state prison. That being a foregone conclusion, I packed up my 1949 Plymouth and headed for the Twin Cities.

From College Boy to LSD and Protest

I eventually found work in the basement of the Pillsbury Company. I spent my days mindlessly churning out office note pads and my nights drinking cheap liquor. The job’s only real perk was that the glue they used to make the note pads got you higher than hell! I eventually met an attorney in the lunchroom who, for some reason, took an interest in me. One day, he said, “kid, you really aren’t as stupid as you sometimes appear to be. Have you ever thought of going to college?” That conversation made all the difference.

While in prison, my family had moved to a small city 90 miles away . . . but I found them! I called up my dad and told him of my latest delusion of grandeur. He was unimpressed; college was not on my family’s radar screen. I asked if I could temporarily live at home to earn some tuition money. Dad eventually relented. When I arrived in Albert Lea, there was only one job opening, and I soon discovered why it was available. The job was at the Land O’ Lakes turkey factory. My job was to pull the live turkeys out of the delivery truck, lift them upside down, and hang them eye-high by their feet as they went in on the conveyor belt for the kill.

I persevered, and within a couple of months, I landed at Austin Junior College. Even for a longshot like me, it was a bet worth taking. They had open admissions, and tuition was the semester equivalent of $7.50 per credit hour. I had enough of a bankroll to pay tuition, rent a $7-a-week room and find a part-time job. It was, at best, a mediocre school with maybe 250-300 students and 15 faculty members. Perhaps appropriately, the college occupied the third floor of the local high school. Nonetheless, it was a college—something that had seemed unattainable just six months before.

To be honest, Red Wing’s remedial courses had accomplished little. It only took a few class sessions to realize that I was in way over my head. During that first year, I had an intimate relationship with the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary. Most evenings, I sat with that dictionary draped across my lap, looking up every seventh or eighth word in my textbooks. At the end of my first term, I received a B- and two Cs. Truth be told, it was close to Christmas and those two C grades were gifts. However, I did make a remarkable discovery midway through my first year of college — cultural capital. From that day forth, I was like a burglar seeking the combination to a bank vault.

Despite that early lack of promise, I soon became the reclamation project of Rod Keller, an erudite sage with contrarian impulses. He saw in me a potential that had escaped the notice of my parents, my K-12 teachers and, most importantly, myself. He prodded, he cajoled, and he flattered: After a couple of years, the liberal arts awoke me from my slumber. I came to realize that for my first 18 years, I had been little more than a sleepwalker—the lights had been on, but nobody was home. I eventually developed an interior compass.

Looking back, that junior college experience reminds me of the cataract surgery I had at age 60. Suddenly the gray, speckled fog that hung over the world metamorphosed into a brilliant, and almost blinding, array of vivid color.

Resembling a body double, I sought to pass as an academic. I took to wearing button-down collar shirts, khaki pants, corduroy jackets, and cordovan loafers. Seeking to repudiate my hardscrabble background, I first parroted the preferences of junior college instructors and, later, research university professors. I even gave up Camel cigarettes in favor of a pipe. Eventually, I pursued honors in both European humanities and American studies at the University of Minnesota. While I had vague ambitions for a doctorate, degrees seemed of little consequence in the late 1960s. I became a perpetual senior, acquiring over 120 semester credits while serving as a teaching assistant.

I took a hiatus from the university in 1967 and returned to Austin, Minnesota, as a reporter for the daily newspaper. Austin was the home of both Spam (Hawaii’s favorite luncheon meat) and a sizable bloc of Nixon’s “silent majority.” I rented a large, old house and it soon became a commune for aspiring hippies and assorted members of the lumpenproletariat. Eventually, I discovered the hallucinogenic drug, LSD, and brought the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test to town.

Oher than having vague anxieties about the draft, the Vietnam War was not yet on my radar screen. One day, I discovered a book lying around the house. In a single evening, I read Arthur Schlesinger’s liberal critique of the war. That polemic was so persuasive that I embarked on a self-directed crash course about the war and the history of American interventionism. I was soon conducting a perpetual teach-in at the commune for anyone who happened to drop by. In the fall of 1967, I organized a motley crew of local clergy, liberal housewives, high school and college teachers, ex-cons and assorted alienated youth, and we set about planning what was one of the first peace marches in Greater Minnesota (we went to great lengths to stress that we weren’t anti-war). As you might imagine, the community did not take well to this disruption of Main Street on a tranquil Saturday afternoon. They lined the streets, pelting us with boos and eggs.

First a commune, then LSD, and finally the peace march—the town’s limited tolerance was finally exhausted. I soon received word of an impending bust. I left town just hours before a posse of local and state police converged on the house. Within days, I was in a Volkswagen bus, driven by a crazed methamphetamine freak, heading for Berkeley and the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco.

A Flower Child’s Trip to the Loony Bin

There is a picture in the Berkeley Barb newspaper that truly is worth ten-thousand words about my stay in the Bay Area. When the French Revolt of 1968 nearly toppled Charles de Gaulle, there was a huge solidarity celebration in Berkeley. The next week’s Barb featured a circle of individual photographs, including revolutionaries like the Black Panther leader, Eldridge Cleaver. There was also a single anonymous hippie, lying on Telegraph Avenue, using the curb as a pillow. Yes, you guessed it. I had just gotten a supply of authentic Owsley acid the day before. “Don’t take more than half a blotter,” warned the dealer; I took two and the trip lasted for 48 hours.

The 1967 Summer of Love was now long gone. The children of darkness, including the likes of Charles Manson, had rolled into town and were preying on the children of light. Like the 19th-century Transcendentalists, the hippie counterculture suffered from something akin to collective amnesia—we were persistently oblivious to the ubiquity of evil. Flower children, lacking the wisdom of the serpent, were no match for the legions of the damned. Murder, rape, armed robbery, and drug rip-offs had become commonplace. The predators got to me as well.

The director of the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic later told my friends that what I had taken to be a capsule of mescaline was actually horse tranquilizer, laced with strychnine. The clinical term for my condition was toxic psychosis; the street vernacular was acid flashback. This was not one of those quaint, momentary lapses from reality but rather a months-long descent into the subterranean regions of the mind, an untranslatable conversation with the demons of one’s unconscious.

The next three years were a season in hell. I found myself intermittently incarcerated on the locked wards of San Francisco General Hospital, the University of Minnesota Psychiatric Unit, and the Rochester and Anoka State Psychiatric Hospitals. This may come as a shock to some, but I was not always a model patient. One fine spring day, I escaped onto the university’s campus-length mall. Feeling an urge to return to a state of nature, I stripped naked and began jumping water sprinklers up and down the mall as if they were high hurdles. Pedestrians must have cracked up watching hospital aides and university police dodging sprinklers as they tried, in slapstick fashion, to capture the lunatic.

Many of you have seen or read One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Every asylum has a Nurse Ratchet or two. Well, her boys were regularly running me down, injecting me with anti-psychotic drugs and throwing me into locked padded cells. After setting fire to a padded cell at the university, they bundled me into a squad car headed for a more secure institution.

Anoka State Hospital was my last hurrah. My psychiatrist was a very proper British expatriate. One day, I approached him near the nurse’s station with questions about what I thought was my impending release. My long hair and hippie garb must have finally gotten to him. His, reply was abrupt and hostile: “You will leave here when you have become socially normal. Go look at yourself in a mirror. You look like some sort of Zulu. I would as soon look like you as run around with my penis hanging out.” While my wits were still somewhat scrambled, I was not witless. “Doctor,” I retorted, “that might be good therapy for you.”

I did not need Erving Goffman or Bob Dylan to figure out which way the wind blows. The next day, my brother Tony helped me escape and we spent the summer roaming the interior of Canada in a Volkswagen bus (for my generation, that vehicle was the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria). It must have been what the Doctor ordered; I have somehow managed to stay out of those loony bins for the last 44 years.

An Accidental Anti-War Leader

During the Vietnam War era, The University of Minnesota’s president, Malcolm Moos, often boasted that his leadership had kept the campus relatively peaceful. That was about to abruptly change in early May of 1972. President Richard Nixon had just escalated the war by mining North Vietnam’s Haiphong Harbor. Within days, Minnesota unexpectedly became the epicenter of the nation’s antiwar movement.

For me, those events were a simple twist of fate. I was just a nameless foot soldier when events began to unfold on the campus’s West Bank early on May 9. There are instances in history when conventional scripts give way to improvisational theatre: Riots are such a moment. In hindsight, my entire life had been a rehearsal for the role I was about to play in this 48-hour drama.

By mid-afternoon, my sense of guerrilla tactics and a bullhorn-enhanced stage presence had catapulted me to the status of an impromptu field commander. By day’s end, we had forced the armed evacuation of an unwelcome visitor (George Romney), Nixon’s cabinet secretary for Housing and Urban Development, and had so disrupted the dedication of Cedar Square West, a much-hated federal urban renewal project, that we became the lead story on the national evening news shows.

The next morning a crowd of 2,000 protesters had gathered on the campus mall. As I stepped before the microphone to propose a strategy for the day’s action, I caught a glimmer of my destiny. Saul Alinsky’s first rule for radicals was to define both that day and my impending activist career — “the action is in the reaction.”

I knew that hidden nearby was the police tactic squad. We wanted to provoke an assault. After trashing the armed forces recruiting office on the edge of campus, I led half the crowd off to storm the ROTC Armory. We tore out the steel fencing embedded in cement that surrounded the military fortress. Dozens of riot police finally poured into the streets, wildly clubbing any available demonstrator. We had achieved our initial objective.

The day then became a sophisticated game of cat-and-mouse. As events unfolded, our ranks grew to over 5,000 protesters. We eventually gained the upper hand. By late afternoon, the authorities had called in all available law enforcement from the seven-county metropolitan area, and they began tear gassing protesters. Even with 250 officers, the mayor and chief of police could not regain control.

In a final act of desperation, they dropped tear gas canisters from a helicopter over a 10-block radius. The fumes engulfed daycare centers, classrooms, local businesses, and major commuter thoroughfares during evening rush hour. We redeployed and managed a counterattack. Our hit-and-run tactics finally forced the governor to occupy the campus with the Minnesota National Guard, 800 troops armed with weapons. For days, we maintained barricades across Washington Avenue, a major route through the university. Fires burned throughout the nights as crowds kept vigil.

City Councilman John Cairns and others wanted to defuse peacefully the standoff. Part of their “soft-power” strategy was seeking assistance from Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy, the anti-war presidential candidate in 1968. He flew in from Washington, D.C. to plead with the occupiers to give up the street. He began to weaken the resolve of some protestors.

The Minneapolis police, the National Guard, and university administrators were about to finally clear the street with a “hard-power” strategy. Just as a massive armed contingent stood posed to attack, the commander ordered them to stand down, He later said, “Clearing the street is not worth getting someone killed.” It was a wise move. Once the bulk of the police contingent departed the campus, it took the steam out of the occupation. Within 24 hours, protesters began withdrawing and the barricades came down

With order restored for a few days, detectives and federal agents hunted me down. I faced several charges. With wire-rimmed glasses, a huge curly ‘fro and a gift for repartee, I became an instant media celebrity—the audacious radical. I had a new identity. My subversive propensities were no longer the negative characteristics associated with a deviant career; my rebellious nature had abruptly become a virtue, qualifying me for a redemptive calling.

President Moos later attributed the failure to pacify the campus to the fact that the protest lacked leadership. Wrong. He never understood the obvious: This was one of those turn of events when power, instead of flowing to those formal leaders recognized by the university, had cascaded into the streets, falling into the hands of a savvy troupe of improvisational leaders. Under pressure from the university’s Board of Regents, Moos submitted his resignation in 1973.

Zen and the Art of Organizing

By 1973, the Sixties had abruptly ended. The revolution had failed to materialize. Many activists, and more than a few hippies, decided to keep their options open by returning to school to either finish undergraduate degrees or enter graduate and professional programs. Not me, I kept the faith by apprenticing myself to the craft of grassroots organizing. To paraphrase Herman Melville, social movements and community organizations became my Harvard and Yale.

During my apprenticeship years, I made every mistake imaginable. The tipping point came when a judge found against me, issuing a $50,000 judgement for libel and slander. After this public embarrassment, I needed a hole in which to vanish. I sought refuge in a skid-row treatment center. I had already failed two 30-day stays at posh facilities. Montana Joe, the center director, stood tall in cowboy boots, a Western hat, and a huge handle-barred mustache. He took one look at me and said, “Monte, from one professional bullshitter to another, your only hope is to stay here for at least 90 days.” I did the time and finally found a congenial A.A. group. After 38 years, I still have Sunday breakfast seven or eight times a year with three people from my original group.

With radical politics in abeyance, I spent the next 17 years spreading seeds of fire, seeking to re-kindle the flames of activism. My guru in those days was Br’er Rabbit. I was an organizer and independent scholar for a variety of organizations that worked with the unemployed, low-income tenants, welfare recipients, union members, and students. I eventually served on the Governor’s Poverty Commission and was the lead author of a study that shaped social policy in the state for the next decade, A Poverty of Opportunity: Restoring the Minnesota Dream.

In the midst of those activist years, Tom O’Connell (an old comrade in arms) invited me to teach a class at Metropolitan State University. Founded in 1971, Metropolitan State was an experimental college for adult learners. Finding myself at a school known for thumbing its nose at the academic establishment, I devised a course that was befitting— “Interpersonal and Social Power: A View from Below.” I taught there for seven years without benefit of a college degree. While this was a pleasurable avocation, I kept my day job.

The Jobs Now Coalition was little more than a rag-tag paper organization when I became its director in 1982. The coalition grew to 32 organizations and soon became the state’s most effective grassroots lobbying operation. I was eventually house at the state’s American Federation of Labor (AFL-CIO) and Teamsters headquarters. With a budget that never exceeded $75,000, Jobs Now wielded significant power at the legislature and in public policy circles. During a five-year period that witnessed the worst recession in the past quarter century, we got the Minnesota Legislature to appropriate $165 million for the nation’s most innovative jobs program, and raise the state’s minimum wage 18 percent above the national rate. I co-authored two evaluative studies of the jobs program that convinced legislators to invest an additional $95 million beyond the initial $70 million.

A Republican majority took control the Minnesota House of Representatives in 1986. Drunk with new power, they called in the Twin Cities’ Catholic Bishops, threating them if they did not back off their social justice agenda. I got wind of the meeting and called one the bishops, asking permission to contact the media. The next day, both statewide newspapers had front pages stories revealing that legislative leaders had bullied the bishops.

Among other accomplishments, we managed to derail a Republican-controlled House of Representatives’ attempt to cut payments for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) by 30 percent. This had been a secret plan until I found a liberal Republican who was willing to expose it to the media. Their “secret” appeared the next morning in front-page headlines. Jobs Now’s successful campaign to defend AFDC played a significant role in the outcome of another event; in the next election, Republicans lost control of the House. By 1987, I had fulfilled my long quest for Zen and the art of organizing.

Dave Roe, the then long-time president of the AFL-CIO, provided a capstone for those five years. On the last day of 1987 the legislative session, we stood looking down two stories at the Capitol rotunda: “All you do is win, Monte,” Roe said, “all you do is win.”

An Obituary and a Pipe Dream

Shortly thereafter, the Minneapolis Star Tribune published a profile of me that was a bouquet. As time passed, I realized that everything in that article was what at age 22 I had hoped would one day be in my obituary. Symbolically, it was an obituary. Soon thereafter, I walked away from a highly visible and successful career. I naïvely decided (lacking a B.A. at the time) to become a college professor.

Lacking an undergraduate degree, I had been teaching three courses per year for five years. Starting in 1989, I spent the next two years honing my craft, teaching 8-10 classes per year as an adjunct. I taught whenever and wherever possible, including repeat performances at every prison in the metropolitan area. In 1991, based on experience and previous publications, the university granted me a B.A. Soon thereafter, I landed a non-tenured sociology position at Metropolitan State. During that first year, I received the Excellence in Teaching Award; and in 1992, the university honored me with the Outstanding Teacher Award. Unfortunately, even after winning both of the university’s teaching awards, I still had not arrived at a safe port. Storms clouds loomed on the Western horizon.

In the early 1990s, Metropolitan State was in the midst of a “hostile takeover.” Legislators, corporate leaders, and state bureaucrats were demanding that the institution jettison its utopian mission. They fired the president and brought in an interim to clean house. In early 1993, he terminated the contracts of 12 of us with non-tenure track appointments. Seeking to upgrade faculty credentials, he initiated national searches for 16 tenure track slots. Backstage sociologists need not apply.

On a cold and snowy March evening, a group of my past and present students held a mass meeting with the acting president. They had moxie enough to bring along reporters. The students were direct and disarming. An article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune quoted Melanie Hardie: “I do believe in credentials and the necessity of being a credible university . . . but not at the expense of my education.”

The president conceded; he would require only a master’s degree for the sociology position and agreed to delay the appointment for nine months. I foolishly took him at his word. His promise did not stop him from recruiting another candidate for the position, giving that person the impression that the fix was in. In spite of that, the search committee made me its first choice. The college dean and academic vice president concurred, checkmating the interim president.

The adage about sausage making might as well apply to the creating of my M.A. thesis. Using a strategy called “opportunistic research,” I have only serendipity for finding the presidential files of the university’s early years stored in a closet that no one knew about. I then spent the next six months in the archives at the Minnesota Historical Society. With less than 48 hours to spare, I finished my historical ethnography and defended my thesis at a very public and well-attended session. Exacting the only remaining revenge available to him, the interim president appointed me to a tenure-track position at the lowly rank of instructor.

In the fall of 1993, the university hired a new president. She took one look at the recent hires and put everyone without doctorates on notice that they were in trouble. Ever the enfant terrible, I was not about to spend my middle ages genuflecting before some dissertation committee. Instead, I decided to conjure up the “illusions and impressions” necessary for an award-winning front stage performance.

The Stranger in Your Midst

If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck . . . I figured I had better quickly find myself a flock of sociologists. That search led me to the annual meeting of the Sociologists of Minnesota. I arrived late that evening and, let me tell you, the last 30 minutes of an SOM cocktail hour is not a pretty sight. I knew not a soul. One of the organizations major domos marched over, tilted her head up at an angle, gave me a perplexed stare and, as only she could do, said in a tone that was as much an accusation as it was a statement of fact: “You’re the guy in the newspaper article.” Since that night, I have been Simmel’s “The Stranger” in your midst:

The stranger will thus not be considered here in the usual sense of the term, as the wanderer who comes today and goes tomorrow but rather as the man who comes today and stays tomorrow . . . He is fixed . . . within a group . . . but his position within it is fundamentally affected by the fact that he does not belong to it initially and he brings qualities into it that are not, and cannot be, indigenous to it. (Levine:143)

I was a stranger to sociology, but the organization made me one of its own. They never asked for papers to affirm my pedigree; nor did they worry about my academic lineage. SOM accepted me at face value and judged me only by my ongoing contributions to the discipline and profession.

If I had made a contribution that the organization considered distinguished, it was because this backstage sociologist had become a reflection of their practices. I have been consistently articulating their message around the nation: SOM is restoring the discipline to its century-old roots—sociologists in Minnesota are leading an insurgency for a more authentic and a more populist sociology.

Coda

In 2007, Warden Otis Zander asked me to return to the juvenile prison at Red Wing to deliver the graduation address. In 2011, I gave the graduation address at the adult prison in Stillwater. For those graduates, I distilled a simple message, drawn from my own life and times.

“Your life story is a series of episodic choices. Your path is never clear when in the midst of living, but you still must make each choice as wisely as you can. As someone once said, “You make the road by walking.” It is only at the end of the journey that you will know what your destiny has been.”

Comments 1

A Backstage Sociologist » The Full Monte — August 29, 2008

[...] invitation comes from an essay of mine, “The Making of a Backstage Sociologist” (which you can read here). That article stems from a speech I gave in 2004 upon receiving the Distinguished [...]