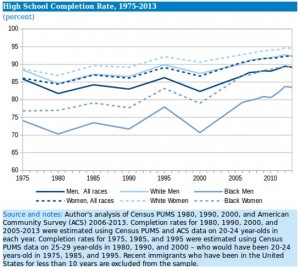

Women – and black women in particular – have seen significant improvements in high school completion rates since the turn of the century, almost cutting in half the black-white gap for women during that time, as I shared last month. But has that meant an increase in college entry and completion – especially since a college degree should demand higher wages in the labor market?

The second report in my Young Black America series of reports examined just that. I found that  young black women and men are entering and completing college at higher levels than in the past. Yet, these gains haven’t been enough to noticeably close the gap between them and their white counterparts.

young black women and men are entering and completing college at higher levels than in the past. Yet, these gains haven’t been enough to noticeably close the gap between them and their white counterparts.

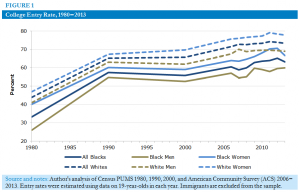

From 1980 to 2013, women had higher college entry rates than men, with white women having the highest entry rates of all (see Figure 1). In 1980, 46.9 percent of 19-year-old white women had entered college (including community college). The college entry rate for white men was 41.0 percent and the rate for black women was 40.0 percent. Black men had the lowest entry rate of 25.9 percent, 14.1 percentage points lower than that of black women.

Since then, college entry rates have significantly increased, with most of the increases occurring between 1980 and 1990. During that time, entry rates for both black and white women increased about 20 percentage points, and rates for white men increased 22 percentage points. College entry rates for black men increased the most, rising 29 percentage points from 1980 to 1990.

Despite making the most progress in entry rates, young black men still lag behind black women and whites. In 2013, the entry rate of black men was 60.0 percent, 34.1 percentage points higher than their entry rate in 1980. However, this rate was still 6.6 percentage points less than black women, 9.0 percentage points less than white men, and 17.9 percentage points less than white women.

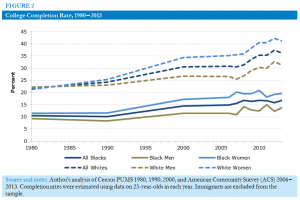

But entry is different from completion. The data on racial gaps in college completion rates were even more striking. Although my analysis of high school completion rates showed a significant convergence between black and white women, the exact opposite is the case with college completion rates (see Figure 2). In 1980, 11.5 percent of 25-year-old black women had completed college with a bachelor’s degree or higher. During the same year, the college completion rate of white women was 21.3 percent, for a black-white gap of 9.8 percentage points.

But entry is different from completion. The data on racial gaps in college completion rates were even more striking. Although my analysis of high school completion rates showed a significant convergence between black and white women, the exact opposite is the case with college completion rates (see Figure 2). In 1980, 11.5 percent of 25-year-old black women had completed college with a bachelor’s degree or higher. During the same year, the college completion rate of white women was 21.3 percent, for a black-white gap of 9.8 percentage points.

Things got worse not better: In 2013, the gap in college completion rates between black and white women was 21.4 percentage points, with completion rates of 19.7 percent and 41.1 percent, respectively. The same is true among men. In 1980, the black-white gap in completion rates for men was 12.9 percentage points, and it increased to 17.6 percent in 2013.

These growing rather than shrinking gaps confirm that there’s more work to be done. Young blacks are 30 percentage points more likely to enter college than in 1980, with entry rates increasing 26.6 percentage points for black women and 34.1 percentage points for black men. These are significant improvements, but remain far behind their white counterparts. Young blacks also still lag almost 20 percentage points behind young whites in college completion rates.

But the growth—rather than continued decline—in black-white gaps highlights the need to examine why these racial gaps persist, and in the case of completion rates, continue to widen.

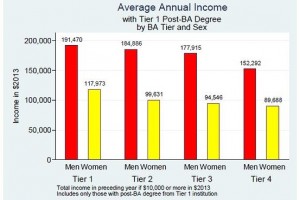

Increases in educational attainment are important, but not just for their own sake. College degrees should lead to higher employment rates, wages, and other labor market outcomes. However, large gaps in completion rates are likely to result in sizable racial disparities in these outcomes. Upcoming installments of my Young Black America series will examine whether that is in fact the case.

Cherrie Bucknor is a research assistant at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. She is working on a year-long series of reports on Young Black America. Follow her on Twitter @CherrieBucknor.