It is my senior year of college and I am adjusting to the fact that in less than a month, I have to go out into the world and decide who I want to be outside of education. Although graduate school is in the future, navigating the world as a Black woman, carrying an abundance of interests, and ultimately just wanting to make the world a better place is at the forefront of my mind. Currently, I am enrolled in a course called “From Margin to Center: Women of Color Doing Public Policy” where I get to learn about women of color in Washington D.C, read their work, and gain personal knowledge and skills through interviewing some amazing women. I had the opportunity of learning from Angela Hanks, Director of Workforce Development Policy at the Center of American Progress (CAP), a policy institute focused on bettering the lives of all Americans through research and action. Her work focuses on promoting workforce development policies that raise wages and employment opportunities of workers. In this interview, I was able to get advice for women of color, like me, who want to shine in the world of policy:

TC: Based on your passions—what do you see yourself doing through your position as the director of Workforce Development Policy at the Center for American Progress?

AH: People who do policy work should always begin and end with the people they’re trying to help in mind. I work in policy because fundamentally, I care about marginalized people – whether it’s workers, women, communities of color, or anyone at those intersections – who face structural barriers to equality or economic security and have little or diminished political power. I also keep in mind that those structural barriers didn’t just appear; they are often the direct result of conscious policy choices. Policy choices that my work can and should help unwind.

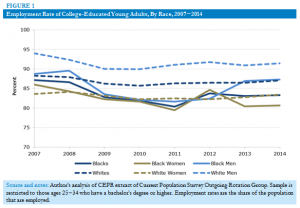

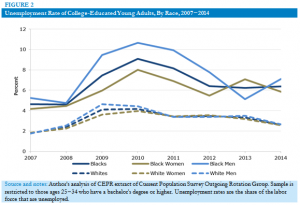

For example, I work on policies to expand apprenticeships, paid training programs that have recently become popular among politicians because they often pay high wages and typically lead to a good job. However, these programs frequently do a poor job of including women at all, and people of color tend to get paid less than their white counterparts. So when I’m working on policy solutions, I tend to focus my attention on how we got here, and what policies are need to ensure POC and women have equal representation in the best jobs.

TC: What is one thing you wish you knew before entering the world of policy?

AH: Probably what policy work actually is? I went to college in D.C. because I thought I liked politics, and immediately declared a political science major at George Washington University. I had no idea what political science was, but it sounded right at the time, so I ran with it. I didn’t even really begin to wrap my brain around what policy is until I interned with my home state senator on Capitol Hill my junior year. The internship was unpaid, so I was only able to work part-time during the school year, while waitressing (pay your interns). Still, something clicked – this was what I was supposed to do. That internship helped me decide to go to law school, and after I graduated I found myself back on the Hill in the job I’d wanted back when I was an intern.

TC: Do you have any advice for young Black women who are interested in attending graduate school, a career, or participate in future work involving social policy?

AH: Know that your voice and perspective are valuable and deserve to be heard. There will literally always be a white guy who tells you he knows better than you – don’t take his word for it. Don’t let his confidence override your qualifications, or make you second-guess your own experiences.

Seek out other Black women in your field. I’m so fortunate to have a supportive network of Black women colleagues and friends at CAP and at other organizations (including the other women you’ve interviewed!) who make navigating spaces with very few people who look like us much easier. It makes a huge difference, I promise. Finding good allies who show you that they value you and your work helps too.

…

TC: What does it come down to? Believing in myself. In a field surrounded by people who might not look like me, as Angela Hanks said, I have to know that my voice and perspective are valuable. In a society demanding to cut the words of women of color out, I have to understand that I deserve to be heard—just like all other women of color deserve.

Tasia Clemons is a senior sociology major at Framingham State University, an Administrative Resident Assistant, and a Council on Contemporary Families Public Affairs Intern; she tweets at @TasiaClemons. Angela Hanks is Director of Workforce Development Policy at the Center of American Progress (CAP). Find her on twitter at @AngelaHanks.

I’m reposting this originally from 6/2/2009, because today is Peggy’s husband John Schmitt’s funeral.

I’m reposting this originally from 6/2/2009, because today is Peggy’s husband John Schmitt’s funeral.

The thought of publishing a book is very seductive. A book offers the opportunity to explain ideas in detail. For some, it signifies an academic arrival. Once you publish a book, you are officially part of the knowledge production machine, you have a compelling way to engage the conversation. My book, on abortion politics [

The thought of publishing a book is very seductive. A book offers the opportunity to explain ideas in detail. For some, it signifies an academic arrival. Once you publish a book, you are officially part of the knowledge production machine, you have a compelling way to engage the conversation. My book, on abortion politics [