For many, summer is a time to exhale, take it easy, and enjoy lazy days at the beach, when one’s toughest decision is whether to read a guilty-pleasure novel or to catch up on back issues of the New Yorker. At least that’s how it looks in the movies. In reality, the gentle breezes of summer often are accompanied by overly ambitious “to do” lists that will never be achieved, and unrealistic (and ultimately disappointing) expectations for family time. Summer is unwittingly a pressure cooker for stress, when our lofty dreams are far removed from reality.

For academics, summer is viewed as the time to finish one’s magnum opus that got left untouched during the school year. Ask an academic what they’re doing this summer, and a nontrivial number will say “finishing my new book.” Although that may be the dream, many (especially working parents) know that uninterrupted work spells can be a rarity, when other duties of summer – like home repairs, child care, and caring for aging parents – emerge. For others, the much anticipated high point of the summer is a family vacation. Despite visions of songs around the campfire and late-night heart to hearts, most of us will experience family vacations in precisely the way we’ve experienced every other family visit – the good, the bad, and the ugly. And as our family members grow older, they simply become amplified versions of their earlier selves. Although the “good news” is that kind and supportive family members grow more so, the bad news is that the cranky control freaks become even more intense.

Mental health researchers have long recognized that it’s not just the presence of negative – illness, job loss, marital spats, traffic accidents – that can impair our psychological health. It’s also the absence of positive, or experiencing less positive than we had earlier hoped for. As far back as 1890, philosopher William James wrote that self-esteem is a result of the balance between one’s actual successes and what one hopes to achieve. More recently, psychologist Alex Michalos’ “multiple discrepancy” theory says that gaps between what we have and what we want are distressing. Psychologist E. Tory Higgins’ “self-discrepancy” theory argues that when there’s a gap between our “actual self” (who we are) and our “ideal self” (who we want to be), depression can result. Yet when there’s a gap between our “actual self” and “ought self” (who we think we should be), guilt and anxiety may emerge. That partly explains the fleeting (though inevitable) feeling of failure when summer ends, and we have not completed our book manuscript, or the long-awaited herb garden remains a dirt mound, or we never made it past the “couch” phase of our “Couch to 5K” fitness dream.

Yet research also shows that most of us overestimate how fun, rewarding, or scintillating an experience will be. The reality simply can’t live up to the dream. Harvard professor Dan Gilbert has documented that most adults are bad at “affective forecasting,” or predicting how happy (or sad) a future event will make them. Even if the long-awaited family trip to the Grand Canyon is joyous, it won’t likely live up to the boundless euphoria we had anticipated. This tendency to overestimate some future encounter is so common that The New York Times Magazine gave it its own name: “tadventure,” or an exciting adventure that doesn’t quite pan out.

Is it inevitable that come Labor Day, we’ll be disillusioned, disappointed, and too despondent to rev up for the upcoming school year? Not necessarily, but it takes some cognitive energy to maintain a positive sense of self. First, avoid social comparisons, or comparing your own accomplishments with others. Many people, especially ambitious types, compare themselves with those at the top of the achievement hierarchy; when we compare ourselves with those at the top, a feeling of self-doubt is inevitable. Second, shed the tendency to “ruminate.” Rumination is continually replaying the disappointing experience in our minds and stewing in our own sadness. Ruminators often intensify their anxiety by fixating on all the things they feel they did wrong.

Third, “just say no” when asked to take on another task that might put you over the edge. Turning down invitations gives us more time to work on the tasks at hand. Saying “no” to an opportunity may lead to that opportunity being passed along to another person who may want or benefit from it more. By “paying forward” a potentially rewarding opportunity, we might also bring ourselves a short-term mood boost.

Fourth, take solace in knowing that as we get older, we’re better able to roll with the punches and each perceived slight or failure takes less of an emotional toll than it did in our younger years. “Emotional reactivity,” or how strongly we feel the slights in our lives, diminishes with age. With age also comes the wisdom that the key to happiness doesn’t lie in adding another publication to one’s CV, or another half-marathon medal to one’s collection. Happiness comes in the process of the pursuit, rather than the end goal.

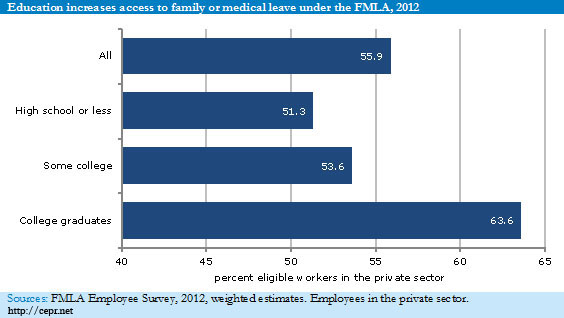

But changing our thought processes isn’t the panacea. Summer stressors are rooted in major societal problems. Employers forced to run “mean and lean” are demanding more and more work from their employees, under shorter and shorter deadlines. Those lucky enough to have stable jobs often find that their responsibilities spill over into nights, weekends, and vacations. Lack of affordable elder and childcare in the U.S. deprives millions of the safety net that Europeans have long enjoyed. And all the while, the media continue to uphold images of those who “have it all,” and do it all effortlessly. Recognizing that we’re doing the best we can, and focusing on what we’ve accomplished (rather than what we’re still hoping to do) may bring some joy back to our summer breaks.

This week the Council on Contemporary Families released a

This week the Council on Contemporary Families released a  Heather Boushey, Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, discusses French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on global economic inequality and spells out its relevance for feminists.

Heather Boushey, Executive Director and Chief Economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, discusses French economist Thomas Piketty’s new book on global economic inequality and spells out its relevance for feminists.

Guest poster

Guest poster

There is a lot to learn from hooking up—including when you talk to people who don’t do it in any kind of stereotypical way. Some of the clichés that seem to get replayed are that “everyone” at college is doing it (70 percent of college seniors have some experience of hookups). And by “doing it” the perception is doing “it” – even though 40 percent of students who hook up reported doing so in their most recent hook up. Another stereotype is that the hookup scene is typically centered around (straight) men’s desires, even if

There is a lot to learn from hooking up—including when you talk to people who don’t do it in any kind of stereotypical way. Some of the clichés that seem to get replayed are that “everyone” at college is doing it (70 percent of college seniors have some experience of hookups). And by “doing it” the perception is doing “it” – even though 40 percent of students who hook up reported doing so in their most recent hook up. Another stereotype is that the hookup scene is typically centered around (straight) men’s desires, even if  This month marks the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s declaration of an “unconditional war on poverty.” Over the next decade, Johnson and his successor, President Richard Nixon, initiated a series of government programs and policies for raising Americans’ living standards. Yet this month also marks over a quarter century since President Ronald Reagan’s 1988 announcement that the war on poverty was over, and that poverty had won. The next decade produced a retrenchment in federal anti-poverty programs culminating in the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, which shifted government priorities toward promoting married couple families as a solution to poverty. To mark the anniversaries of these very different approaches to the government’s role in poverty reduction, the Council on Contemporary Families circulated two briefing reports that put poverty reduction, poverty rates, and policy responses to poverty in perspective.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s declaration of an “unconditional war on poverty.” Over the next decade, Johnson and his successor, President Richard Nixon, initiated a series of government programs and policies for raising Americans’ living standards. Yet this month also marks over a quarter century since President Ronald Reagan’s 1988 announcement that the war on poverty was over, and that poverty had won. The next decade produced a retrenchment in federal anti-poverty programs culminating in the 1996 Welfare Reform Act, which shifted government priorities toward promoting married couple families as a solution to poverty. To mark the anniversaries of these very different approaches to the government’s role in poverty reduction, the Council on Contemporary Families circulated two briefing reports that put poverty reduction, poverty rates, and policy responses to poverty in perspective.