Part 1 in a series

The online platform turned national organization project — Black Lives Matter — started as a call to action against anti-Black racism following the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the neighborhood watch volunteer who fatally shot unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin.

According to The New York Times, the jury rejected the prosecution’s argument that Zimmerman deliberately pursued and started what became a lethal fight with Martin because he assumed he was a criminal. The verdict wasn’t a surprise, certainly not to black people who have experienced and/or witnessed similar outcomes over and over again. Alicia Garza, a co-creator of Black Lives Matter, explained in a Colorlines interview:

A lot of what we were seeing on Facebook and in our conversations was, “I knew they would never convict [Zimmerman]. He would never go to jail.” For us, it wasn’t actually about using the criminal justice system to solve our issues. For us, it’s really about asking, “Do black lives matter in our society?” and what do we need to do to make that happen. We know that someone going to jail is not going to make black lives matter. What’s going to make those lives matter is working hard for an end to state violence in black communities, knowing that that’s going to benefit all communities.

The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter soon became a rallying call. Within days of tweeting it out, Garza teamed up with Patrisse Cullors, executive director of the Coalition to End Police Violence in L.A. Jails, and Opal Tometi, who runs the Black Alliance for Just Immigration. Together, these women started a dialogue about what it means to be black in this country, to be the target of a system of anti-Black racism.

The persistent, strained relationship between law enforcement and African Americans that has led to a string of police-related incidents and fatalities is part of that system. The fatal shooting of yet another unarmed, black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri, followed by yet another grand jury decision not to indict the white police officer who shot him, begs the question again: Don’t black lives matter?

Recurring incidents like these across the country shine a dim light on the everyday biases and racial, political, and socio-economic structures that uphold racial inequalities and privilege whiteness. But Black Lives Matter is not just about racism; it’s about anti-Black racism.

At this critical time, we, as social scientists, have an opportunity not only to support those seeking transparency, accountability, and safety in their communities, we can examine ourselves, and be proactive in our own work.

What biases do we hold? How do we help to perpetuate racism in our institutions, and specifically anti-Black racism? How might we engage in critical dialogue in ways that will transform our institutions to make black lives matter? What actions can we take to support this growing movement, not only through our classroom teaching, but also informally in our work with students, in our research and how we use that research, in our public sociology, and for some, in direct action?

We’ll be reflecting on these questions here. Please share yours. And we will continue the discussion in the next few blog posts.

Read the entire Black Lives Matter Series on Feminist Reflections

- Part 1: Don’t Black Lives Matter? by Gayle Sulik

- Part 2: How Sociologists Can Support Black Lives Matter by Mindy Fried

- Part 3: An Open Letter to Student Activists by Meika Loe

- Part 4: Racism is not Dead: Language And Everyday Interactions by Trina Smith

More Information:

On the movement:

- A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement by Alicia Garza, The Feminist Wire, Oct. 7, 2014.

- Facing Race Spotlight: Organizer Alicia Garza on Why Black Lives Matter, by Jamilah King, Colorlines, Oct. 9, 2014.

- Meet the BART-stopping woman behind “Black Lives Matter” by Heather Smith, grist, Dec. 4, 2014.

- The Unprecedented Scale of the #BlackLivesMatter Protests by Kriston Capps, The Atlantic, Dec. 5, 2014.

- #FergusonNext: Here’s how to end the school-to-prison pipeline, starting now by Katherine Krueger, The Guardian, Dec. 10, 2014.

- The Disruption This Time by L.A. Kauffman, The Baffler, Dec. 7, 2014.

- An Open Letter of Love to Black Students: #BlackLivesMatter, Black Space, Dec. 8, 2014.

- Hands Up Don’t Shoot, a mini-documentary which includes interviews from students and faculty from the UMass Amherst campus discussing the issue of the young, black, and unarmed gunned down by the police.

- Women of Color on #BlackLivesMatter, Gender, and Racism, Third Wave Fund, Dec. 11, 2014.

Related:

- Class, Race, Gender and U.S. Policing by Michelle Renee Matisons, Black Agenda Report, Dec. 10, 2014.

- ‘The Alarm Bells are Ringing’: From Athletes to Environmentalists, a Universal Call for Racial Justice Emerges, Common Dreams, Dec. 9, 2014.

- The new threat: ‘Racism without racists’ by John Blake, CNN, Nov. 27, 2014.

- Black Congressional Staffers Plan Ferguson, Garner Walkout by Tim Mak, The Daily Beast, Dec. 10, 2014.

- We Must Stop Police Abuse of Black Men by Eric Adams, The New York Times, Dec. 4, 2014.

- Unarmed People of Color Killed by Police, 1999-2014 by Rich Juzwiak and Aleksander Chan, Gawker, Dec. 9, 2014.

- Where Do We Go After Ferguson? by Michael Eric Dyson, The New York Times, Nov. 29, 2014.

- Here’s the Data That Shows Cops Kill Black People at a Higher Rate Than White People, Jaeah Lee, Mother Jones, Sep. 10, 2014.

Reflections from The Society Pages:

- A Sign of Progress: Michael Brown Could Not Be “Willie Hortoned” by Elizabeth Rapaport, Dec. 9, 2014.

- Racism, Punishment and the Lives of Young Men of Color by C.J. Pascoe, Dec. 3, 2014.

- Ferguson and Football by Doug Hartman, Dec. 2, 2014.

- Anti-Consuming Ferguson by David A. Banks, Dec. 1, 2014.

- When Force is Hardest to Justify, Victims of Police Violence Are Most Likely to be Black by Lisa Wade, Nov. 28, 2014.

- Covering the Three Missouri Michaels by Steven Thrasher, Nov. 26, 2014.

- Ferguson, The Morning After by Doug Hartman, Nov. 25, 2014.

- Reflecting on Ferguson by Evan Steward, Aug. 26, 2014.

- Teaching Ferguson by Todd Beer, Aug. 25, 2014.

How white people can fight racism:

- The White Conversation on Race by Carla Murphy, Colorlines, Dec. 9, 2014.

- Some tips for white people who have opinions about Ferguson by Juliana Britto Schwartz, Feministing, Dec. 10, 2014.

- 10 Simple Ways White People Can Step Up to Fight Everyday Racism by Derrick Clifton, Everyday Feminism, Sep. 27, 2014.

- Ferguson: White Bodies Bearing Witness by Jenny Davis, The Society Pages, Nov. 28, 2014.

- Ferguson Syllabus from Sociologists for Justice, Aug. 23, 2014.

On Protesting:

- Plan on Protesting? What You Should Know About Your Rights and the Powers the Police Have, by Steven Rosenfeld, Alternet, Dec. 6, 2014.

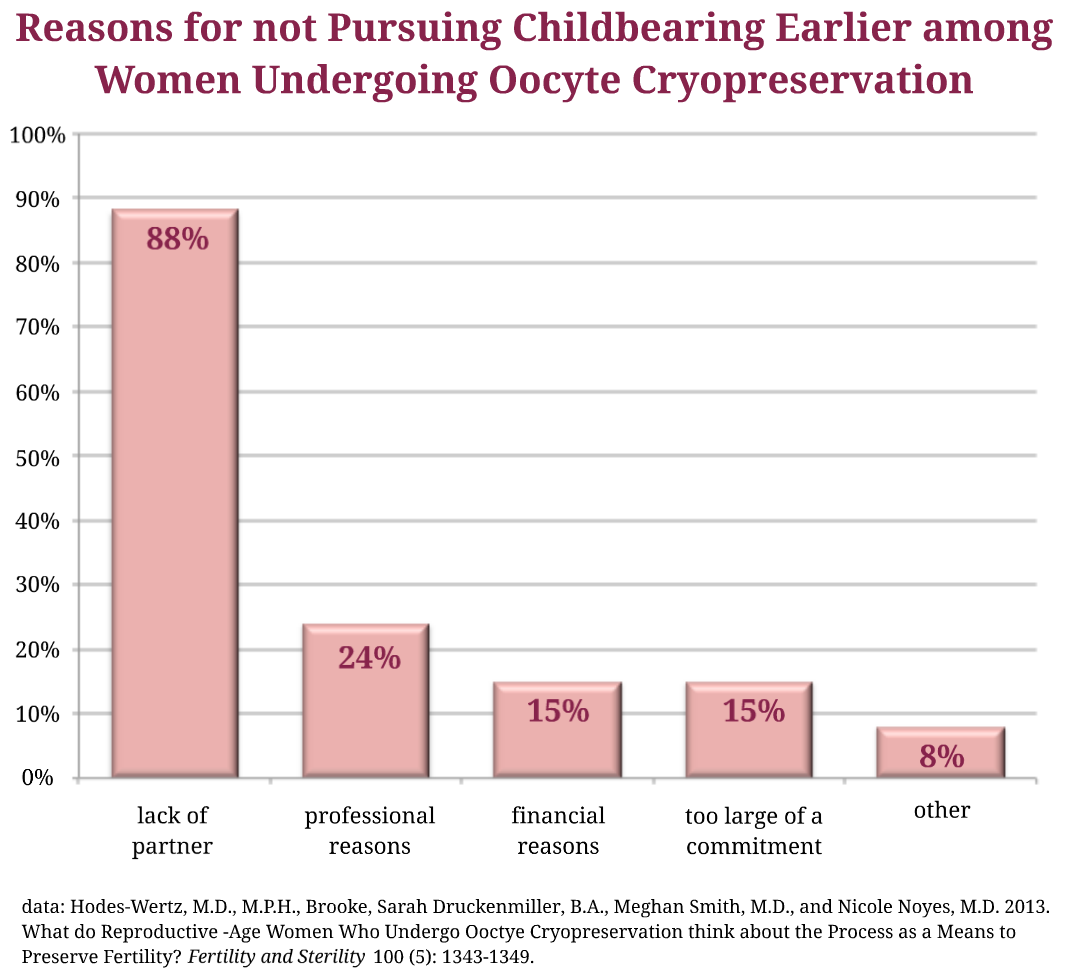

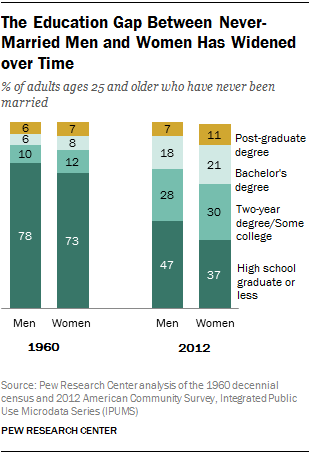

While they were allowed to select all of the possible reasons that might apply, only about a quarter of the sample cited “professional reasons” for not having children earlier. The overwhelming majority of women (88%) claimed that “lack of partner” was the primary reason (see our adapted graph).2

While they were allowed to select all of the possible reasons that might apply, only about a quarter of the sample cited “professional reasons” for not having children earlier. The overwhelming majority of women (88%) claimed that “lack of partner” was the primary reason (see our adapted graph).2 Indeed, as

Indeed, as

uring and after the Anita Hill/ Clarence Thomas trial, a wrinkle that the film does not address.

uring and after the Anita Hill/ Clarence Thomas trial, a wrinkle that the film does not address.

There is something that is bothering me about the phrases, “A real man doesn’t hit a woman,” or “No one should ever hit a woman.” This seems to be the go-to phrase in response to the video of Ray Rice punching and knocking out his wife. A friend with tickets to an NFL game wanted to wear a t-shirt that represented her commitment to girls’ and women’s rights. One person suggested, “Don’t Hit Girls.” On the surface, who could argue with that?

There is something that is bothering me about the phrases, “A real man doesn’t hit a woman,” or “No one should ever hit a woman.” This seems to be the go-to phrase in response to the video of Ray Rice punching and knocking out his wife. A friend with tickets to an NFL game wanted to wear a t-shirt that represented her commitment to girls’ and women’s rights. One person suggested, “Don’t Hit Girls.” On the surface, who could argue with that? Mimi Schippers

Mimi Schippers