The floor plan of the White House recently made headlines because of a subtle change that’s caused a bit of a stir: it now features a gender-neutral restroom. Just one. But one was enough to make headlines. Many people don’t think twice about which restroom to use in public. Some people’s choice, however, is more of a dilemma than you might assume. Many transgender individuals struggle with the restroom issue in public settings. And this is an issue that forces cis-gender folks to confront deeply held beliefs about a gender-segregated setting—beliefs some may not fully realize they hold and many may be ill-equipped to discuss.

Making use of a public restroom is not often understood as a political act. Yet, a group of transgender folks in the U.S. and Canada are participating in a bit of digital activism by doing just that. It’s a quiet social movement, but it’s already gained some media attention. Pictures posted alongside the hashtags #Occupotty, #WeJustNeedToPee, and less often #LetMyPeoplePee on all manner of social media are starting a much-needed conversation about gender in and around public restrooms.

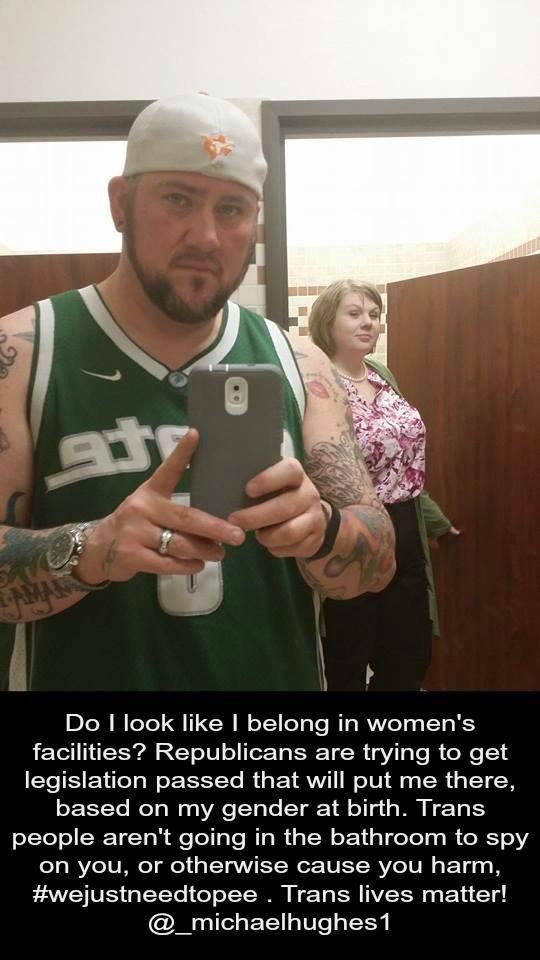

Brae Carnes is a transgender woman living in Victoria, Canada whose photo-activism went viral when she posted an image of herself applying lipstick in a public restroom with a line of urinals against the wall behind her (see left). Brae told reporters at the Times Colonist, “I’m giving them what they want… I’m actively showing them what it would look like if that became law and how completely ridiculous it is” (here). And Brae is not alone. Michael Hughes, a transgender man living in Minnesota, also caused some digital waves when he posted a series of pictures of himself in women’s restrooms with captions like: “Do I look like I belong in women’s facilities?” (see below). Brae and Michael are part of a vocal group of trans* rights activists opposing legislation that would force transgender people to use the public restroom facilities associated with their birth gender (the sex they were assigned at birth). So-called “bathroom bills” are being introduced in the U.S. and abroad, and #Occupotty is an important challenge to the proposed legislation.

Those introducing bathroom bills most often justify them as being about “protection,” “public safety,” and as attempts to reduce violence and assault. The bills rely on the transphobic myth that transgender individuals are sexually perverse and that they are likely to be sexual predators. Thus, defenders of these bills often claim that they are about protecting cis-gender people. This avoids the troubling truth that transgender individuals are far more likely to have violence committed against them than they are to commit this kind of violence against others. Indeed, Media Matters found no evidence to substantiate the claim that restroom sexual assaults were higher in trans-inclusive jurisdictions. One survey of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in Washington D.C. found that 70% of respondents reported having been either harassed in, assaulted in, or denied access to public restrooms (see here). It’s an important issue and Brae Carnes and Michael Hughes are helping to draw more attention to the lives that hang in the balance.

Those introducing bathroom bills most often justify them as being about “protection,” “public safety,” and as attempts to reduce violence and assault. The bills rely on the transphobic myth that transgender individuals are sexually perverse and that they are likely to be sexual predators. Thus, defenders of these bills often claim that they are about protecting cis-gender people. This avoids the troubling truth that transgender individuals are far more likely to have violence committed against them than they are to commit this kind of violence against others. Indeed, Media Matters found no evidence to substantiate the claim that restroom sexual assaults were higher in trans-inclusive jurisdictions. One survey of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in Washington D.C. found that 70% of respondents reported having been either harassed in, assaulted in, or denied access to public restrooms (see here). It’s an important issue and Brae Carnes and Michael Hughes are helping to draw more attention to the lives that hang in the balance.

Bathroom bills portray trans* persons as sneaky and deviant and as attempting to trick the rest of us into using a restroom with them. But, as Mic.com reported, there have been zero reported attacks on cis-gender people by transgender people in public bathrooms. All of the documented attacks victimized trans* persons. So, why is the conversation about transgender people committing violence rather than about protecting transgender folks from cis-gender violence?

This is an instance of what Laurel Westbrook and Kristen Schilt call a “gender panic”—situations in which people collectively react to challenges to biology-based ideologies about what gender is and where it comes from by attempting to reassert those ideologies. Bathroom bills produce just this type of ideological collision where biology-based ideologies and identity-based ideologies are pitted against each other in public discourse. Inside this ideological discord, we gain new information about the gender binary, gender inequality, and how our beliefs about gender difference take a lot more work to uphold than we may assume.

Bathrooms are intensely gendered spaces. The belief that men and women, boys and girls, ought to relieve themselves in separate rooms is a powerful illustration of our collective investment in gender differences. But, sex-segregated bathrooms are a matter of social preference and organization rather than being recommended by our biology. And when we attempt to resolve this gender panic by resorting to biology (such as introducing legislation mandating the criteria of “birth gender” for public restroom use), we continue an awful tradition of putting transgender people at risk of violence under the guise of protecting “us” from “them.” But, social scientific research shows that we are in far greater need of policies that protect “them” from “us.”

Bathroom segregation is a political issue and one that deserves academic and public feminist support. The proposed legislation relies on myths associated with cis-gender and transgender people alike. Whether motivated by hate or misunderstanding, these laws fail to acknowledge well-documented facts about violence against transgender people, and in doing so, play a role in perpetuating continued violence and discrimination against transgender people. #Occupotty is a political statement and a request for recognition and rights. But these brave digital activists are doing more than that, too. They are exposing a set of myths that also work to justify gender and sexual inequality. Whether openly acknowledged or not, it is for this reason that #Occupotty meets resistance and it is for this reason that it deserves more support.

#TransLivesMatter

An article published in the

An article published in the  Change in Higher Education

Change in Higher Education

Kristen Barber is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She teaches courses on gender, inequality, work, and qualitative methods and is on the Gender & Society Editorial Board. Her book on women working in the men’s grooming industry is forthcoming with Rutgers University Press.

Kristen Barber is an Assistant Professor of Sociology and a Faculty Affiliate in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. She teaches courses on gender, inequality, work, and qualitative methods and is on the Gender & Society Editorial Board. Her book on women working in the men’s grooming industry is forthcoming with Rutgers University Press.