Adjunct: “a thing added to something else as a supplementary rather than an essential part”.

I’ve been teaching Sociology as an “adjunct” for nearly 20 years. I never liked this descriptor, but I learned early on that most students don’t know or seem to care about my title or my status, and for me, that’s the bottom line. I have found that students are oblivious to stratification within academia – the cascade of titles and honors that starts with part-timers at the bottom, and then officially begins with Assistant Professor, the tenuous first step which initiates the gradual and arduous climb up and up, until – if lucky – one reaches Associate, Full and eventually, at the far end of the career spectrum, Emeritus, the end of the line, after decades of classes taught, research conducted, peer-reviewed articles and books published, talks given and dissertations advised.

When prospective parents and students tromp around campus, asking all the right questions, they are rarely prompted to ask one of the most relevant questions: “Will my professors be part-time (low-paid) labor?” No, if they ask anything related to the status of teachers, they want to know if the professors have doctorates, and often the answer is “yes”, avoiding the issue of labor stratification altogether.

That said, most students just assume that their teacher is the professor, unless that teacher is still a graduate student. In fact, in every undergraduate class I have taught, students insist on calling me “Professor”, even when I tell them to call me by my first name. I generally stop short of telling them about my status in the academic chain; I also don’t tell them that they may never see me again because I’m not sure if I’ll be re-hired. I have had some teaching jobs where students are shocked when, at the end of the semester, they hear I might not be back the following year. Sometimes, that opens up the conversation about stratification within the academic labor market. After all, this is Sociology, where issues of class, gender and race are paramount. Why not insert one’s own “social location” into the mix?

The increase in employment of part-time, adjunct faculty in academia has become an “issue” for some university systems, especially when union contracts or state laws limit the number of part-time faculty. Despite bloated administrative budgets and the building of new athletic centers and sports arenas designed (in some places) to make an institution more “competitive”, the teaching staff is where pennies are pinched.

Adjunct teaching an add-on rather than central

Teaching as an adjunct is not my “full-time work”; it truly is an adjunct to my career, in which I co-run a small social science consulting group called Arbor Consulting Partners (www.arborcp.com). In other words, thankfully, I don’t depend on this income as my “bread and butter”. Teaching is my passion but it’s really hard to make a living teaching as an adjunct.

I have been lucky to not be at the bottom end of the adjunct pay scale – which can be as low as $2,000 per course, but the wages generally hover around $5,000-6,000 at many research universities, unless you’re teaching at one of the “prestige” institutions. Many adjuncts piece together a string of teaching gigs, sometimes as many as 6 classes per semester and sometimes in different institutions, just to pay the bills. They/we receive no benefits, and while they are teaching a full load, they often don’t have an office – or if they do, they share it with all the other part-timers, so it’s hard to use for meetings with students or to get any work done. Adjuncts can work their butts off and still be poor and disenfranchised.

Generally, an adjunct functions outside of the system. We’re not paid to go to meetings or advise students. This is fair, given that we’re only paid to teach. But for those who would like to be more involved – and even be considered for a tenure track position – this status can be a liability. New hires in academia are judged for their ability to teach and advise students, and in research universities, they are judged by their academic scholarship. Adjuncts rarely have time to pursue their own research, and if they do, it’s on their own dime, unless they have sought and received a grant, which is harder to do without an institutional base. Some universities even disallow part-timers from receiving university grants.

Having the capacity to teach many different courses is central to any adjunct’s survival. I have taught a variety of Sociology courses in a range of academic institutions, including courses on aging, sex and gender, feminist theory, work and family policy, gender and leadership, and most recently, a course on Evaluation Research, which is the work I do as a consultant. For some of those jobs, I had a one-year contract, but mostly, I have been teaching by the course and by the semester, with the possibilities of returning, which I have now happily done in three of the institutions where I have taught. Generally, I have either replaced a professor who is on-leave, taught a course that full-time faculty didn’t have time to teach, or more recently, I have taught courses that no one else has the expertise to teach.

One thing that I love about teaching at the university level is the freedom to design a syllabus, regardless of whether a course has been taught by another professor. Not all adjuncts get to do this. Over the years, I have experimented with incorporating the arts into my teaching, and invariably, other professors (those on the ladder) tell me they think it’s really cool. I have been lucky that, for me, teaching as an adjunct is a choice. I have also had some incredible colleagues, supportive and inclusive. But many adjuncts do not feel they are treated as equals relative to full-time faculty.

Unionizing the adjunct labor force

There is a growing movement to unionize this low-paid contingent labor force, and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the American Federation (AFT) of Teachers are two of the major unions now leading the charge nationally. A dozen new union locals have been established, including one at Tufts University, where I got a one-year contract right after I completed my doctorate, and another at Lesley University, where one of my friends, a fully tenured faculty member, played a key role. Both were organized by SEIU.

So where do I stand? I strongly believe that it is in the interests of all parties within academia for Part-time Faculty to be paid well and have good working conditions, including consistency in the courses they teach and multi-year contracts, as this contributes to the overall quality of education at the institution. At the same time, Universities should not rely so heavily on part-time labor. The slow creep of an unstable labor force comprised of part-time contracted workers is a disservice to students, their parents and the institution overall.

At Tufts, part-time faculty members successfully negotiated a contract that included 22% pay raises over a 3-year period, longer-term contracts, and the right to be interviewed for full-time positions in one’s department. In addition, their contract stipulates that adjuncts who teach three or more courses over the academic year will have access to health, retirement, tuition reimbursement, and other employee benefits. This is a major victory for part-timers and the University, overall.

Historically, it has always been challenging to organize “professional” workers, given the notion that labor unions are associated with blue-collar workers, not teachers or nurses or social workers, who are falsely considered “above that”. But frankly, this notion is just a way to hold back the collective strength of workers from having more power. The move to organize adjunct labor – just like the move to organize all workers who are underpaid and undervalued – is critical not just to the individuals who directly gain from union representation; it is also critical for the broader society and economy.

A recent article in the Harvard Crimson describes the working conditions for its “non-ladder” faculty, or put in more plebeian terms, adjunct faculty. Harvard can call these workers what they want, but they are still contingent labor. Adjuncts at Harvard and other Ivy’s get paid sometimes twice or three times what adjuncts at less prestigious institutions get paid. But unlike tenure track faculty, they are subject to short contracts, far lower wages than their colleagues, and lower status than their colleagues. An exception to this is when the Ivy’s hire former politicians or entrepreneurs who command high wages to teach a course because of the prestige they bring to the institution. For the “average” non-ladder employee at Harvard, the institution affords a status akin to a post-doc, a coveted year following the completion of one’s doctorate which may be devoted to research. This is because teaching at Harvard, even as a “non-ladder” employee, carries the imprimatur of a fancy-labeled institution. Surely, one would think, if that institution is hiring this person to teach their students, they must be smart by association.

Bigger questions must be raised about whether universities are going to depend more fully on lower-waged contracted workers. The system of tenure, where faculty members are essentially hired for life, has been subject to debate for many years, posting the question: Is the tenure system critical to protecting intellectual inquiry, and/or is it a system that rewards decreasing productivity? But this thinking avoids the real issues. The tenure system is not to blame for the rise in part-time contracted labor in academia. We must, instead, look at bloated administrative budgets and the trend to create amenities to attract students, particularly those paying full-freight.

David Kociemba, President of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) at Emerson College, where he teaches in the Department of Visual and Media Arts, is quoted as saying the adjunct movement is “four decades in the making”, but he was able to finish the union drive at Emerson College in only two months. This just demonstrates how ready some part-time faculty members are to get organized, given the opportunity.

So far, I have not been at an institution during a union drive for adjunct labor. That is perhaps another casualty of life as a “sometimes adjunct”, or any adjunct for that matter, given that these part-time workers aren’t tethered to the institutions where they teach. But I imagine that if I do continue to teach courses here and there, I will eventually sit in the eye of the storm, and instead of supporting the movement from the sidelines, writing blog posts and signing petitions, I will add my voice to the collective. While I don’t count on my adjunct jobs to pay the bills, I wouldn’t mind…

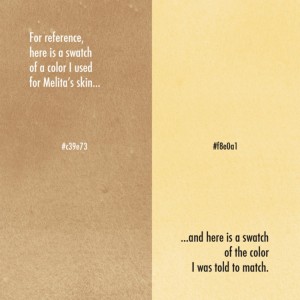

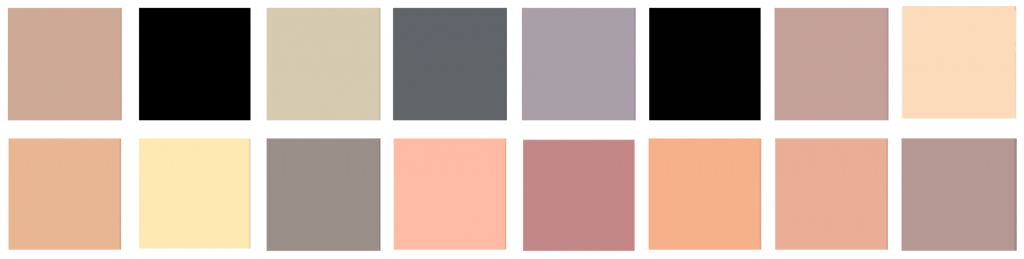

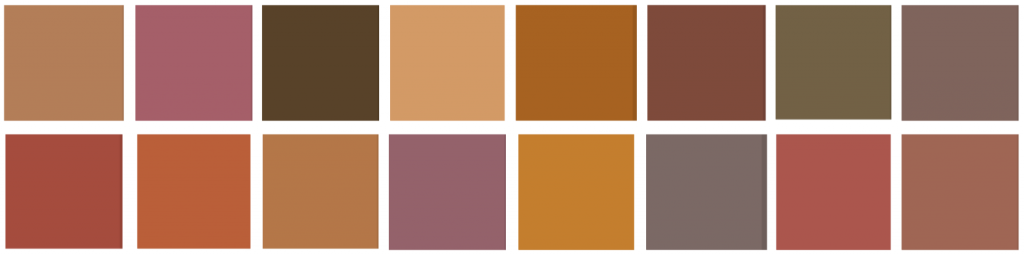

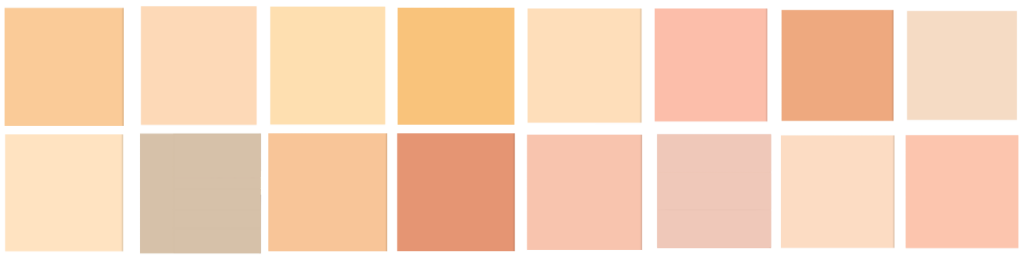

In the panel of the cartoon reproduced here, you can see Wimberly’s original color swatch for the character alongside the swatch he was instructed to use for the character.

In the panel of the cartoon reproduced here, you can see Wimberly’s original color swatch for the character alongside the swatch he was instructed to use for the character.

Now, perhaps it was unfair to use Batman as a comparison as his character is more often depicted at night than is Wonder Woman—a fact which might mean he is more often depicted in dynamic lighting than she is. But it’s an interesting thought experiment. Based on this sample, two things that seem immediately apparent. Amazing-man is depicted much darker when his character is drawn angry. And Wonder Woman exhibits the least color variation of the three. Whether this is representative is beyond the scope of the post. But, it’s an interesting question. While

Now, perhaps it was unfair to use Batman as a comparison as his character is more often depicted at night than is Wonder Woman—a fact which might mean he is more often depicted in dynamic lighting than she is. But it’s an interesting thought experiment. Based on this sample, two things that seem immediately apparent. Amazing-man is depicted much darker when his character is drawn angry. And Wonder Woman exhibits the least color variation of the three. Whether this is representative is beyond the scope of the post. But, it’s an interesting question. While

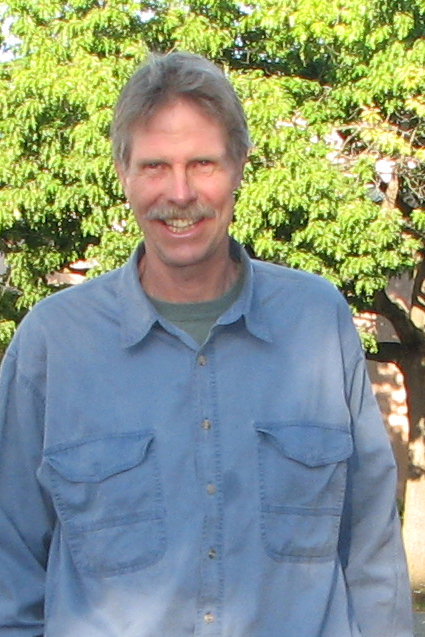

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before.

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before. Michael A. Messner

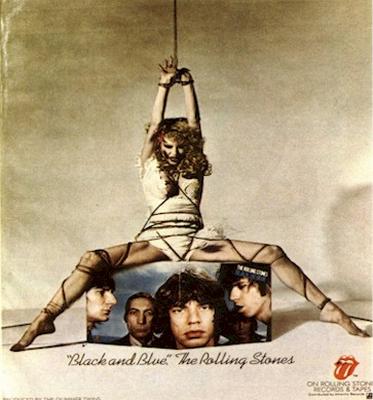

Michael A. Messner Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.

Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.