Google the words “Beyoncé and Feminism” and you get a mind-blowing number of hits. (Go ahead, Google it, I can wait…)

There’s been a flood of questions about the topic ever since the pop star opened up about her new brand of modern-day feminism in Vogue.UK. Is Beyoncé a feminist? Isn’t Beyoncé a feminist? Is Beyoncé’s brand of feminism “real?” Does it help or hurt the Feminist project? What happens if everyone becomes a Feminist?! Would this dismantle everything we know about feminism? Won’t someone please make the official declaration so we can all go back to watching cats on YouTube!

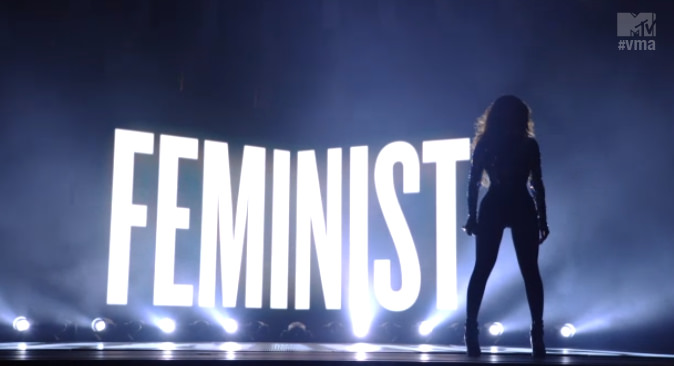

Maybe things aren’t so desperate. But the chatter about Beyoncé and her feminism— in the wake of the 2013 release of the Beyoncé Visual Album and the image of Bey standing in front of a giant, glowing “Feminist” sign during her 15-minute performance at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards — certainly created a rift among some groups of feminists and others.

The Beyoncé-Feminism debates have had an almost Kinsey-Scale feel to them: from extreme arguments about Beyoncé’s use of her body and sexuality as a form of terrorism for Black women (see discussion with bell hooks) to declarations that Beyoncé is a bad influence on all good girls and women, including married women and their husbands, and children (see comments from Bill O’Reilly). In the middle of the scale, we have folks who acknowledge that Beyoncé’s image and music may/may not run contradictory to what is/is not Feminist.

More interesting to me is the way this conversation is affecting pop culture. Suddenly, talking about feminism and discussing how patriarchy affects society is okay, even encouraged.

Women’s function in pop music has mostly been as eye candy. Look good. Do what you’re told. Sing the song created by a male production team. Numerous books have chronicled the evolution of women in pop music. A few examples are Gender in the Music Industry by Marion Leonard, She Bop II by Lucy O’Brien, and my book Sing Us a Song, Piano Woman: Female Fans and the Music of Tori Amos). These books share a theme: if a woman bares her body she will be judged from those chasing a standard of purity and from feminists who see this action as submission to the male gaze. Even though it is missing from the debates, this is where I see the contention: Beyoncé is challenging the passivity of the male gaze, setting a foundation for a new wave of feminists who simultaneously celebrate their bodies and provide cunning intellectual fodder.

Listening to Beyoncé’s self-titled album, we hear a woman speak about marriage, sex, motherhood, post-partum depression, religion, death, miscarriage, revolution, feminism, and her identity as a Black woman. We hear this woman authoritatively express her views and define them on her own terms. While some bristle at Beyoncé using her body as a means of seduction, for example in her “Partition” video, the song expresses the inner thoughts and feelings of many women who have concerns about men’s expectations of sex. In the song “Flawless,” Bey sings lines like, “I took some time to live my life/but don’t think I’m just his little wife” and then launches into a spoken word piece by renowned Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie who illustrates the dynamic of struggle for many women and girls: “We teach girls to shrink themselves, to make themselves smaller. We say to girls, “You can have ambition, but not too much. You should aim to be successful but not too successful. Otherwise you will threaten the man.” In the song “Mine,” with lines that address post-partum depression and concerns about her marriage, Beyoncé presents a multi-dimensional portrait of life. To me, this all sounds feminist.

Women’s identities are largely missing in pop music because the genre is so focused on one-note presentations of womanhood. But Beyoncé’s songs have become anthems for many women because they are written from an “I” perspective that speaks to the messiness of women’s lives. We all have contradictions, even feminists, that may make us seem less perfect in the ways we live out our vision of the world. To argue that Beyoncé is/is not feminist because of a song she sings, something she wears, or the way she carries herself on stage may be counter-productive. There is a reason why so many feminists were amazed and bewildered to see Beyoncé stand in front of that neon “Feminist” sign. The act was defiant, declarative, and gave a new generation of women a gateway to feminism.

The Beyoncé-Feminism debates beg the question: Will feminism get to a point where as long as the core is focused on equality, people (even entertainers) can “do feminism” in a way that makes sense to them without being judged? After all, many people with diverse political orientations agree on the principle of equality even if they have different ideas on how to get there. Feminism is more fluid than many of us would like to believe.

I’ve come to a decision. I think we want Beyoncé Knowles in the corner of feminism. She has the platform to shine a spotlight on issues related to women and girls (as she has done here and here). She has amassed such power through her music that when she speaks, people listen. She can rally people with a simple song release. To me, that is a feminist using her power constructively. And if there is a beat we can dance to, even better.

________________

Adrienne Trier-Bieniek PhD is a gender and pop culture sociologist. She is the author of Sing Us a Song, Piano Woman: Female Fans and the Music of Tori Amos (Scarecrow Press, 2013) and co-editor of Gender and Pop Culture: A Text-Reader (Sense, 2014). Her writing has appeared in various academic journals as well as xoJane, The Mary Sue, Gender & Society Blog, Feministing, and Girl w/Pen, and she runs the Facebook page Pop Culture Feminism. Adrienne Trier-Bieniek is a professor of sociology at Valencia College in Orlando, Florida.

Adrienne Trier-Bieniek PhD is a gender and pop culture sociologist. She is the author of Sing Us a Song, Piano Woman: Female Fans and the Music of Tori Amos (Scarecrow Press, 2013) and co-editor of Gender and Pop Culture: A Text-Reader (Sense, 2014). Her writing has appeared in various academic journals as well as xoJane, The Mary Sue, Gender & Society Blog, Feministing, and Girl w/Pen, and she runs the Facebook page Pop Culture Feminism. Adrienne Trier-Bieniek is a professor of sociology at Valencia College in Orlando, Florida.

Comments 1

Gayle Sulik — December 6, 2014

An insightful comment from Elizabeth on Facebook: "I think it is very interesting that some define feminism as a set of beliefs and others as a lifestyle. From a core belief perspective, feminism is pretty straight-forward. The tricky bit is translating it to a large set of complex behaviors, carried out by very different individuals."