At Girls Rock Camp, a week-long summer camp for girls and non-binary kids, volunteers plug instruments into amplifiers. Once “plugged in,” campers excitedly ask, “Is my amp on? Can I turn it up? How can I make it louder?” These campers, ages 9 through 17, know how to crank up the volume. They experiment with different sounds— leaning into the microphones, turning-up amp knobs, and yelling call-back chants into an imagined crowd: “Who rocks? GIRLS ROCK! Who rocks? GIRLS ROCK!”

As young people start to discover (and use) their voices, things can get LOUD. Carving out space for femme expression and empowerment, volunteers encourage campers to be unapologetic about their voices and their volume. Crashing cymbals and turned-up amps are the norm—punctuated with shrieks, sharp microphone feedback, and unexpected elbow-slides on the keyboard. There is no template for what we are doing here. Resistance is messy and wild and loud as hell.

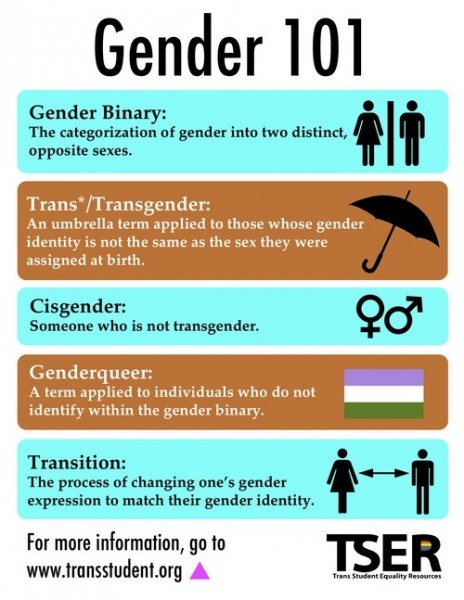

And make no mistake, resistance is important at Girls Rock Camp. The program offers girls and non-binary kids opportunities to engage in self-expression. The camp prides itself on helping girls build self-esteem through music education, collaboration, and performance, as well as through empowerment and social justice workshops. In many ways, Girls Rock Camp is an enclave for social resistance. Campers are encouraged to push back against oppressive gender norms. They are asked to rethink binary assumptions about bodies and gender identities. And volunteers design workshops to teach and promote consent, acknowledge gender and racial privilege, and to challenge oppressive heterosexist systems that maintain inequality.

At Girls Rock Camp, one way campers challenge these systems is by coming together to write original song lyrics and performing these songs live in front of family and friends at a public venue. This can be a challenging exercise. Many of the campers have never written a collaborative piece before camp. This process, however, serves as an opportunity for young artists to address specific concerns in their everyday lives. One band, The Ultra-Violet Vixens, wrote lyrics that exclaim: “Femme isn’t fragile! All your expectations are vile. We won’t listen to what others say; we rock in our very own way!”

Vixens’ message challenges the assumption that femininity is inferior, or less valuable, than masculinity, and they declare that social expectations for girls are indeed “vile.” These lyrics contradict the popular notion that girls are expected to be quiet, weak, or docile. Speaking out against these stereotypes allow campers to constructively push back against oppressive gender norms. Refusing to believe that all girls need to be submissively similar, the band declares that they “rock in their very own way!”

During a House committee hearing in 2017, Representative Maxine Waters famously quipped that she was “reclaiming” her time. As I engage with young folks at Girls Rock Camp, I am reminded that, in many ways, they are reclaiming their voices. Girls are routinely told to sit still, to take up less space than boys, and to be quiet. Here— both on stage and during band practice—girls and non-binary kids are anything but quiet. They are plugged into amps and speakers and microphones—they are going to be heard.

The voices of girls and non-binary kids are amplified through the organizational efforts of Girls Rock Camp, which helps campers learn how they might resist the structural and interpersonal barriers they encounter in their own lives. For both adult volunteers and campers, turning up the volume is a political act. Campers have space to express, loud and clear, that their words matter. Girls Rock Camp serves as a timely reminder that we need to amplify messages of change and resistance, and that young people need to be a part of this conversation. They too want to push back against structures that are designed to usher them off stage.

**All photos taken by Mitch Mitchell. Used with permission.

Trisha Crawshaw is a Ph.D. student in Sociology at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. Her dissertation research focuses on gender, youth culture, and resistance narratives in the Girls Rock Camp community. This is her third year volunteering with Girls Rock Carbondale, a music education program that promotes self-esteem and expression for young girls and gender queer children throughout Southern Illinois.

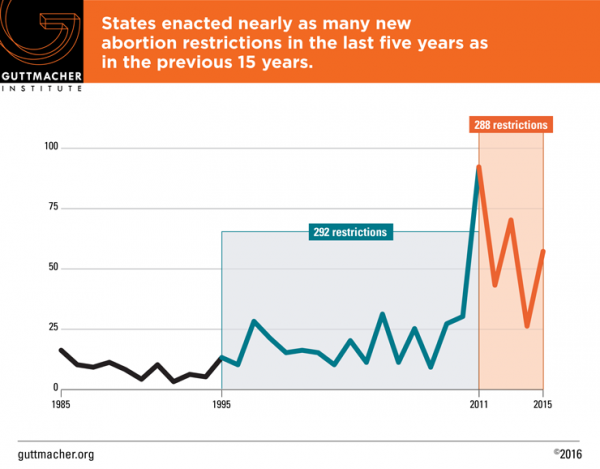

With a 5-3 vote, SCOTUS ruled that H.B.2 created an undue burden for the women of Texas. And the female justices played a

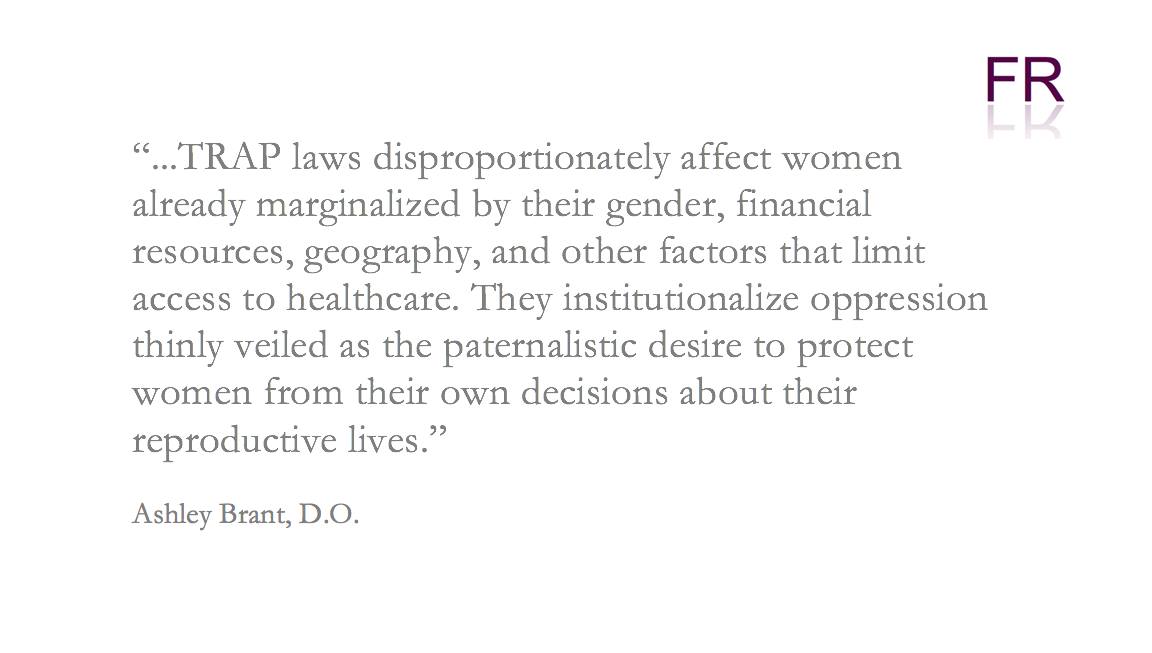

With a 5-3 vote, SCOTUS ruled that H.B.2 created an undue burden for the women of Texas. And the female justices played a  Ashley Brant, DO, MPH is an obstetrician-gynecologist and abortion provider. She completed her residency at Baystate Medical Center in western Massachusetts. Her research focuses on contraceptive access and medical education. She currently practices in Washington, DC.

Ashley Brant, DO, MPH is an obstetrician-gynecologist and abortion provider. She completed her residency at Baystate Medical Center in western Massachusetts. Her research focuses on contraceptive access and medical education. She currently practices in Washington, DC.

don’t feel constrained by their mission to help, but rather are moved to choose jobs based on their individual intellectual curiosities. I am confident that if giving back is in their heart, then they will find a way to help people by becoming social workers, teachers, attorneys, doctors, engineers, chemists, or graphic designers. So, my dear students, be selfish. And while you are at it, do your best in whatever field you choose. I’m sure you will positively impact a life or two or more along the way.

don’t feel constrained by their mission to help, but rather are moved to choose jobs based on their individual intellectual curiosities. I am confident that if giving back is in their heart, then they will find a way to help people by becoming social workers, teachers, attorneys, doctors, engineers, chemists, or graphic designers. So, my dear students, be selfish. And while you are at it, do your best in whatever field you choose. I’m sure you will positively impact a life or two or more along the way.