Merriam-Webster announced on Twitter yesterday that it added “cisgender” and “genderqueer” to its dictionary. This is big news for gender and sexuality scholars and activists, who have long been fighting for the legal equality and social acceptance of LGBTQ. Oxford added the terms to their dictionary in 2015, so Merriam-Webster is a bit behind the curve. But at a time when state legislators are promoting and passing new laws to deny the identities of, restrict the movement of, and allow discrimination against gender and sexual minorities, this institutionalization of language reflects a larger move toward inclusion (see here, here, and here).

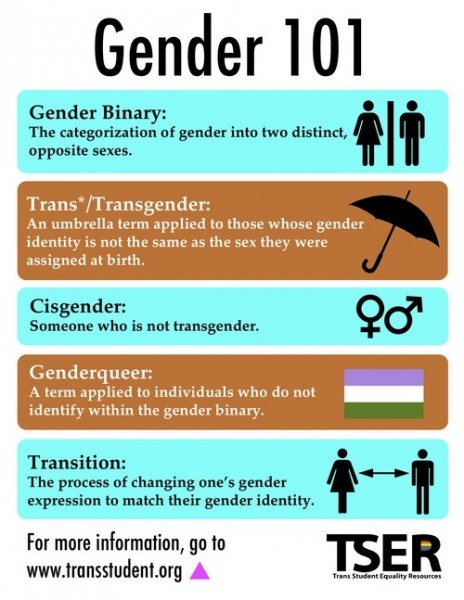

English, like all languages, is constantly evolving, and gender scholars emphasize its importance is not just in reflecting existing cultural trends but also in creating new possibilities. Language and gender are simultaneously formed, and in recent history it has established dichotomies that suggest there are two clear categories into which people fall: male/female; and thus two clear ways people should identify, appear, and behave: masculine/feminine. And we have an elaborate language to stigmatize people who fall outside of these binaries, including “sissy,” “fag,” and “dyke.” Some people might label cisgender men—men who identify with the sex they were assigned at birth—as “fags” if they don’t participate in the collective sexual objectification of women, for example. Prove you’re masculine, this word suggests, and make sure it’s straight.

But language that sets up binaries of any kind is inadequate because it will never fully reflect the diversity of people’s desires, identities, or practices. This inadequacy of course does serve a purpose by naturalizing the existence of some and making “others” deviant or invisible, and invisible people don’t get rights because they technically don’t exist. Advocates of identity politics make it clear that labels are important in pulling marginalized groups out of invisibility, and so “lesbian,” “gay,” “bisexual,” and “transgender” help us have a larger discussion of sexuality. Similarly, “cisgender” allows us to examine the privileged norm, and this is an important turn.

“Genderqueer,” which refers to an individual whose gender identity is neither, both, or a combination of male/female, or otherwise cannot be labeled, is a uniquely important term because it pushes back against the notion that gendered categories are stable in the first place. While gender scholars and theorists alike are popularly teased for coining too many terms, coming up with language to reflect diversity and to challenge our current way of thinking is a crucial part of gender revolution. To understand that change is possible first requires us to have a language for imagining what the world might look like if change occurred. In other words, new language can allow some to imagine a world they never thought possible.