Dear Incoming Members of Congress from the Tea Party,

Do you like clean tap water? How about our scenic and toll-free interstate highways? Do you think 911 service and the fire department are neato?

Then you like taxes! Because taxes pay for all those things, and without taxes, we can’t have them. That’s not socialism–that’s civilization, built up over centuries of debate and experimentation in solving the problems that human societies face.

Have you considered what it would be like to return to a world in which your home would be allowed to burn down if you didn’t display a placard over your door indicating that you’d purchased the right kind of private fire insurance? Do you know why we don’t do that anymore? Because we tried it, and it didn’t work. Some problems cannot be reduced to individual property and individual risk—they can’t be privatized away.

Taxes aren’t a conspiracy to deprive you of your wealth. They pay for a lot of stuff you use. And don’t go all squidgy over the redistribution of those taxes to the poor. If you find them all undeserving, then remember that programs originally intended for them, like Social Security and Medicaid, are increasingly providing economic lifelines for middle- and upper-middle-class people too.

In fact, the richer you are in the United States, the more you make out like a bandit in terms of the benefits you enjoy versus your share of tax burden. Take it from a guy who is much, much richer than you will ever be:

There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.

Now that we’ve got that cleared up, please send in the social conservatives. Salt N Pepa want to have a little chat with them about Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.

Sincerely,

Brooke

Comments 3

Shawn — December 17, 2010

Brooke, I thought you might have an opinion about an American bank risk analysts' comments about the Danish mortgage system: "The reason that the Danes have such an orderly mortgage market is because like much of Europe, their people have only the freedoms allowed by the state."

Here's a more complete extract:

We start this comment with an excerpt from Ian Jack's review of Fintan O'Toole's new book, Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger. Both are must reading for students of the crisis around the world. And conveniently enough, you have but to change the words of either of these works to include American politicians and states to show that the stories on both sides of the pond were remarkably similar.

Speculative booms are the result of free people doing greedy, short-sighted and stupid things to benefit themselves at the expense of everyone else. We invite you to examine the new book by our friend Alex Pollock at American Enterprise Institute, Boom and Bust: Financial Cycles and Human Prosperity, wherein he writes:

"Despite their historical frequency, the busts at the end of the bubbles take people by surprise. Then they ask the same questions. How did it happen? How did prices get out of control? How did so many risky loans get made? Who is guilty. What can we do so it never happens again?"

Well, sad to say that the whole point of being a free society is that booms and busts will happen again. The Irish and their American cousins share this terrible but also wonderful attribute. When the desire for individual freedom and opportunity runs into the reality of a zero sum world, there is fraud and larceny. Sad to say, when Americans arrive at the point of perfectly managed regulatory perfection we shall all being living in a Euro-style corporate dictatorship. The reason that the Danes have such an orderly mortgage market is because like much of Europe, their people have only the freedoms allowed by the state. And fraud and corruption in Europe are largely the province of politicians and their clients among the largest banks and corporations. Indeed, America is well along in the journey down that road to serfdom, in part because we still are unwilling to punish the outliers and thereby restore balance between individual aspirations for a better life, call it the American dream, and the public good.

Link to full article (watch out, it gets put behind a $ub$cription wall after a few days):

http://us1.institutionalriskanalytics.com/pub/IRAMain.asp

Shawn — December 17, 2010

Brooke, I think you are arguing a "reductio ad absurdum" (if my Latin is correct). The challenge of economics and public policy is a struggle BETWEEN the desire to privatize and the desire for public operations.

Some economics classes start with a discussion of why there isn't "just one big firm" that allocates all goods and services, from oil to food to iPads. The answers are obvious: specialization and varying risk levels for different businesses that require different capital structures and investments. I think you run the risk of concluding that the government should be the "one big firm" (but now I'm nearing a reductio ad absurdum).

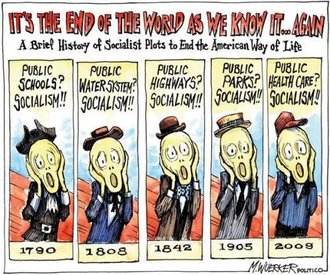

Consider each of the examples listed in the political cartoon:

1. Public schools: private schools continue to thrive, and have made public schools more accountable since school choice laws were made during the Reagan years.

2. Public water system: many people still have well water, and there is also a thriving private market for bottled water. Seems harmonious enough to me.

3. Public highways: here I think the economic jury has concluded that private roads rarely work, due to economies of scale. BUT: witness Chicago's sale of the Skyway toll road to a private firm.

4. Public parks: again, I have to agree. From a stakeholder (vs pure economic) perspective, open space must be set aside by the sovereign or it will be put to ostensibly "productive" use. Not all parks can (or should) be on top of landfills, although that's a great example of public/private partnership.

5. Public health care: here, I refer to William Easterly, author of many books on development aid. Writing in the Financial Times a few years ago (sorry, no cite), he noted that if health care is a human right, the challenge is that YOU CAN NEVER HAVE ENOUGH HEALTH CARE. Therefore cost-benefit analysis by government is impossible.

Before we raise up public operations supported by taxes too much, please also consider Michael Heller's book on the "tragedy of the anticommons", in which public property is poorly utilized. Link to great podcast interview with the author:

http://www.econtalk.org/archives/2009/11/heller_on_gridl.html

Michael E. Marotta — January 23, 2011

It is too easy to accept that the way we do things now is the way they always were done, or must always be done. Just as base-10 is not the only way to count, "taxes" are not the only way to pay for common services. And "taxes" is in quotes because there are many ways to levy them.

Bridge tolls were mentioned above. The Ohio Turnpike (and other state turnpikes and toll roads) are called "use taxes." The sales taxes on gasoline also pay for roads. Thus, we do not tax homeowners for the construction and maintenance of roads they may not actually use. And those who do use them (a lot) pay (a lot) in gasoline taxes for the convenience of paved roads.

Some people never use a city park - often they can be warrens for crime. Danger aside, it is simply a matter of lifestyle that you might pay the entrance fees and camping fees for a state park, but never use a free city park. Just lumping them all together does not help the analysis.

City parks can be free - but the retailers are contract concessions, not from the city Hotdog Department. So, much else in a park can also be contracted, including maintenace. Conversely, even (free) city parks may have sign-ups to reserve picnic areas, especially for pavillions, maybe with nominal fees or deposits.

Money for parks can come from city property taxes or from local sales taxes. It may seem like a moot point, but during the Great Depression of the 30s, Detroit in particular, but other cities as well, floated their own scrip, backed by future tax collections. With landed property, that was computable. With sales taxes, it is less certain.

All of that simply opens the door to discussing private providers. Cleveland's Euclid Beach Park was privately-owned and enjoyed by the public for decades as an institution.

(See here: http://ech.cwru.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=EBP). Similarly, the Cleveland Museum of Art is a private endeavor, established for the benefit of the community. It is free. Many people contribute cash on entrance nonetheless. Rich people endow the museum, of course. But it is not paid for with taxes.

As for the fire department, they are nice. But the biggest gains in public safety came not from tax-based fire fighting but from the obsolescence of open fires in the home: no more fireplaces, no more wood burning stoves, no more coal burning furnaces.

Another factor was safe electrical design. We lived in a beautiful old farm house that we miss ... except for its have exactly one outlet in each room. The first house we bought was built in 1932. We upgraded the service to 200 amp. Fire departments are a blessing, to be sure, but even if they save 75% of a home, you are still pretty much homeless. Only the insurance company gets the benefit of the service.

The biggest problem with taxes in a society that seeks to minimize coercion is that you are punished as a criminal for not paying them. It would be an interesting exercise in economic sociology to think of ways to turn voluntarism and opportunity toward public benefits now paid for with coercion.