“Steve, what did we decide to codename her?”

Steve clicked through his notes. “Turnkey, sir.”

“Turnkey? Who the hell came up with that?” Raymond knew The Agency was running out of codenames, but this was ridiculous. As a top official, he had enough on his mind; how was he supposed to keep track of this shit?

“Well, I think it’s because—”

“So does that mean we’re moving ahead?” Isobel interjected.

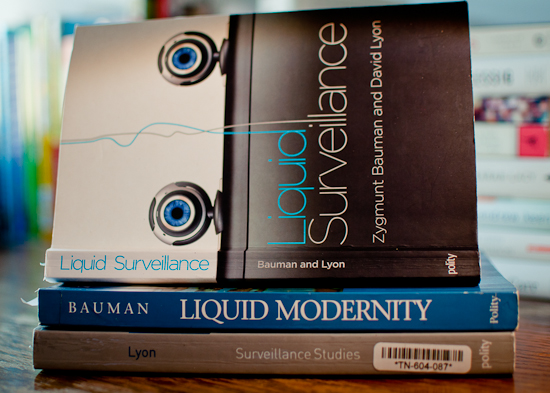

“The data is there,” said Michael. “We’re positive she has one of the stronger connections to Wedge that we’ve been able to identify. The frequency of their SMS communication alone—plus the fact that they so often text late at night—indicates that this is clearly more than a working relationship.”

“Not to mention,” Patricia added, “that Occupy essay they wrote came out almost a year ago. If it was purely a working relationship, they’d have no reason to still be in contact.”

“So you think they’re lovers?”

“Well, we’re not certain yet,” Michael replied. “I’ve got Steve filing for a warrant to go through the SMS content, and her email content as well. We’re hoping she’ll turn out to be less opaque than Wedge—” more...