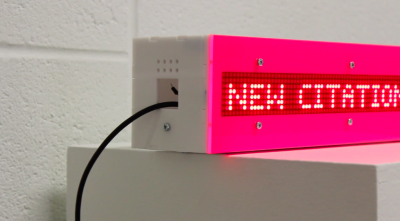

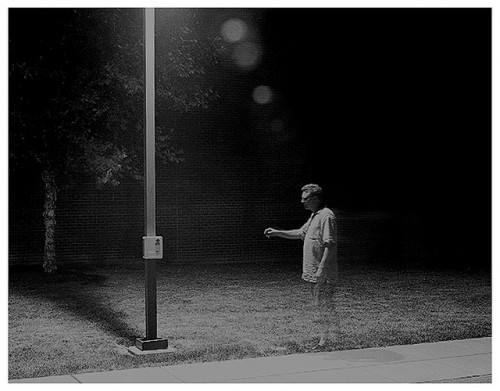

When the team here at Cyborgology first started working on The Quantified Mind, a collaboratively authored post about the increasing metrification of academic life, production, and “success”, I immediately reached out to Zach Kaiser, a close friend and collaborator. Last year, Zach produced Our Program, a short film narrated by a professor from a large research institution at which a newly implemented set of performance indicators has the full attention of the faculty.

For my post this week, then, I’d like to consider Zach an Artist in Residence at Cyborgology—someone using the production and dissemination of works that embody the types of cultural phenomena or theories covered on the blog (as it turns out, this is not Zach’s first film featured on Cyborgology). I suppose it’s up to him if he’d like to include the position on his CV. In the following, I would like to present some of my reactions to the film and let Zach respond, hopefully raising questions that can be asked in dialogue with the ones presented at the end of The Quantified Mind. In full disclosure, I am very familiar with Zach’s scholarship and art (I’m listed as a co-author or co-artist on much of it, though not Our Program in particular), so I hope I don’t lead the witness too much here.

But first, the film: