There is a trend—one that was present prior to the election but has increased dramatically since—in our inability to communicate with people who hold radically different political convictions. It is a complete systems failure. On the smaller end of the scale, it takes form in the specialized vocabularies that we do not share, the differences in language use that muddy conversations and leave us confused. Higher up the scale are the different sources we rely on for news, the different windows to the world that deliver information to us and form our basic conceptions of reality. And at the top of this systems failure is something more difficult to discuss, let alone solve. It is a crisis of epistemology—the ways we come to know the world—that is bound up in the collapse of trust in fundamental institutions, and an apocalyptic paranoia that everyone you disagree with is knowingly working toward the destruction of your way of life.

There is a trend—one that was present prior to the election but has increased dramatically since—in our inability to communicate with people who hold radically different political convictions. It is a complete systems failure. On the smaller end of the scale, it takes form in the specialized vocabularies that we do not share, the differences in language use that muddy conversations and leave us confused. Higher up the scale are the different sources we rely on for news, the different windows to the world that deliver information to us and form our basic conceptions of reality. And at the top of this systems failure is something more difficult to discuss, let alone solve. It is a crisis of epistemology—the ways we come to know the world—that is bound up in the collapse of trust in fundamental institutions, and an apocalyptic paranoia that everyone you disagree with is knowingly working toward the destruction of your way of life.

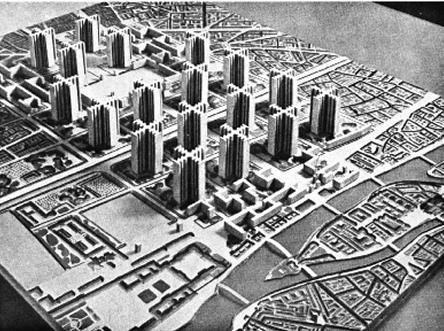

“The motor has killed the great city. The motor must save the great city.”

-Le Corbusier, 1924.

In the fast and shallow anxiety around driverless cars, there isn’t a lot of attention being paid to what driving in cities itself will become, and not just for drivers (of any kind of car) but also for pedestrians, governments, regulators and the law. This post is about the ‘relative geographies’ being produced by driverless cars, drones and big data technologies. Another way to think about this may be: what is the city when it is made for autonomous vehicles with artificial intelligence? more...

Fake news among the alt-right has been central in post-election public discourse, most recently instantiated through Donald Trump’s dubiously sourced tweet about the “millions of illegal voters” supposedly driving Clinton’s substantial lead in the popular vote. Less attention, however, has been paid to the way “real” news is, to use Jurgenson’s term, “fact-i”. Based in data and empirical accounts, mainstream news gets cast as respectable and objective vis-à-vis the fabrications and embellishments that go viral in right wing echo-chambers. This is especially true when journalists, stack of papers and obligatory pen studiously in hand, point to statistics that back up their reports.

Fake news among the alt-right has been central in post-election public discourse, most recently instantiated through Donald Trump’s dubiously sourced tweet about the “millions of illegal voters” supposedly driving Clinton’s substantial lead in the popular vote. Less attention, however, has been paid to the way “real” news is, to use Jurgenson’s term, “fact-i”. Based in data and empirical accounts, mainstream news gets cast as respectable and objective vis-à-vis the fabrications and embellishments that go viral in right wing echo-chambers. This is especially true when journalists, stack of papers and obligatory pen studiously in hand, point to statistics that back up their reports.

Such reliance on, and valorization of, “data” masks the human underpinnings of journalistic practice and the ways that things become numbers and those numbers become stories. So here I present a cautionary tale of a small missing data point, with big narrative consequences.

A couple of years ago I wrote about Friendsgiving, that very special holiday where cash-strapped millennials gather around a dietary-restriction-labeled potluck table and make social space for their politics and life experiences under late capitalism. All still very relevant, though I suspect this is the year where we should come up with a name for whatever happens after late capitalism. Some of you, of course, will be sharing a table with people not of your own choosing and so you might be forced into reckoning with people who make excuses for Nazis and disagree that trans people exist.

What follows are a couple of useful tactics that will help you hold your own and get through arguments that we shouldn’t have to keep having but here we are. These probably will not help you in a completely hostile room. These are better if you’re in a mixed crowd and you want to make sure that at the end of the political argument people don’t leave saying nothing more than “politics is so divisive!” People only criticize divisiveness when they aren’t sufficiently convinced by one side. more...

On Friday night, VP-elect Mike Pence went to see Hamilton. He was loudly booed. The cast delivered a respectful message asking him to “work on behalf of all of us”. President-elect and noted internet troll Donald Trump accused the cast of harassment, because the truth is whatever he says it is. By Saturday morning, it was – going by my feed – most of what Twitter was talking about.

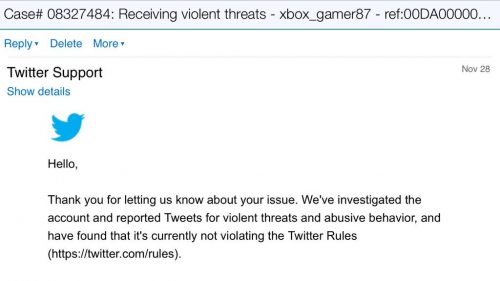

It’s probably appropriate that amidst a torrent of harassment and abuse directed at marginalized people following the election of noted internet troll Donald Trump, Twitter would roll out a new feature that purports to allow users to protect themselves against harassment and abuse and general unwanted interaction and content. Essentially it functions as an extension of the “mute” feature, with broader and more powerful applications. It allows users to block specific keywords from appearing in their notifications, as well as muting conversation threads they’re @ed in, effectively removing themselves.

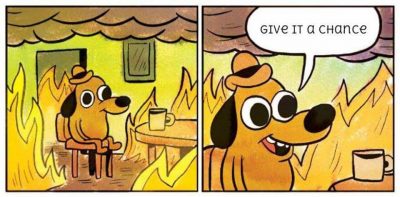

“It’s time for unity.” “We need to listen to each other more.” “Now that it’s over, things can get back to normal.” “Who knows, maybe he won’t do all that stuff.” “Let’s give him a chance.”

This is what it often looks like when liberals and moderates who didn’t support Trump try to come to terms with his election. To quell their own fears. To quell the fears of others. To tamp down the vitriol and partisanship of a long, ugly campaign. To make amends with the relatives on Facebook whom they all-caps yelled at, to signal to their Twitter followers that they are folding themselves into the new normal, and to atone for being blindsided by an election result that many had already predicted—primarily those most effected by a Trump presidency: immigrants and people of color.

Calls for unity and prayers that his campaign was mere showmanship are not only a coping mechanism, but a performance as well. It’s trite to say that any post on social media is a performance, though that does not make it less true. And politics itself is a performance. But I believe the performance of reasonability in this particular climate has important, perhaps dire, repercussions for all of us, and more so for the most vulnerable and disenfranchised among us.

My writing this was inspired prior to last week’s result by an article from May of this year, which proclaimed 2016 as the first “internet election.” The author, Andrew Keen, was less concerned with rigorously defining what an “internet election” might entail, and more interested in throwing a variety of questions at 2016 in order to rip it away from the course of standard electoral discourse. The barely-implicit question, of course, was to explain away what seemed––at the time and until last week––the outlier that was Donald J. Trump.

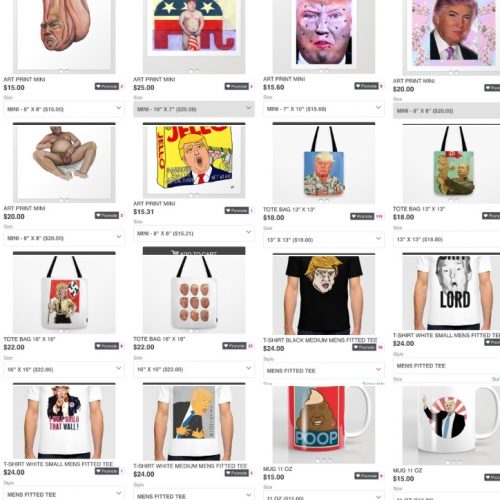

The internet has been saturated with Trump memes. Some times they are hilarious, some times they are hurtful. Some times they bring relief, some times they are agonizing. This post is a product of my observations and archive of Trump memes and their evolving power from “subversive frivolity” to “normativity”. I demonstrate how Trump memes have transited along a continuum as: attention fodder, subversive frivolity, the new normal, and popular culture.

Screengrabs with the black header were archived from the mobile app version of 9gag on 8 November 2016, around 0001hrs, GMT+8 time. They include all the posts tagged “Trump”, with the earliest backdating to 14 weeks. There were 141 original memes in total but a handful have been omitted from this post. Screengrabs without the black header were archived from various news sites and social media throughout the Election season.

Editor’s Note: This essay originally ran on November 9, 2016 and included a call to politics of affinity. On November 10th, I added to the essay by applying the framework to ongoing protests.

As the reality of the 2016 election results sunk in, my echo-chamber of a leftist newsfeed was full of two key things: heartbreak and I told you so’s. The heartbroken expressed disbelief that the U.S. would elect a person with an impressive record of bigotry coupled with an appalling record of incompetence. The I told you so’s said they already knew. Not knowing was a sign of privilege, naivety, foolish trust in big data. We should have nominated Bernie, they said. You should have voted, but not for Jill Stein.

Donna Haraway, so keen on blurring boundaries, promotes what she calls affinity politics, vis-à-vis identity politics. more...