During the week of July 12, 2004, a group of scholars gathered at Stanford University, as one participant reported, “to discuss current affairs in a leisurely way with [Stanford emeritus professor] René Girard.” The proceedings were later published as the book Politics and Apocalypse. At first glance, the symposium resembled many others held at American universities in the early 2000s: the talks proceeded from the premise that “the events of Sept. 11, 2001 demand a reexamination of the foundations of modern politics.” The speakers enlisted various theoretical perspectives to facilitate that reexamination, with a focus on how the religious concept of apocalypse might illuminate the secular crisis of the post-9/11 world.

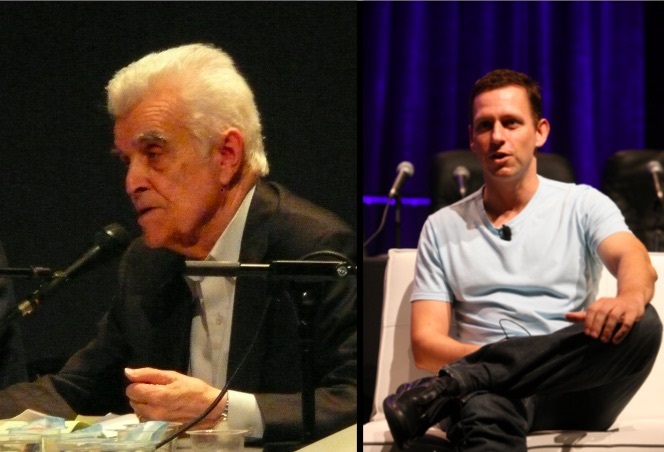

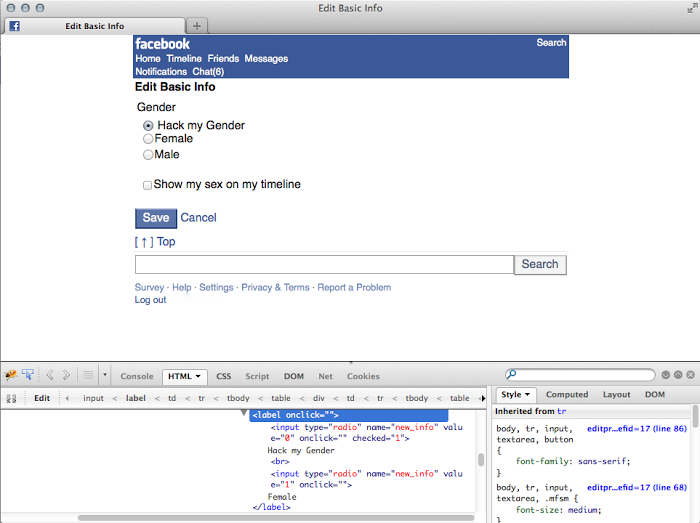

As one examines the list of participants, one name stands out: Peter Thiel, not, like the rest, a university professor, but (at the time) the President of Clarium Capital. In 2011, the New Yorker called Thiel “the world’s most successful technology investor”; he has also been described, admiringly, as a “philosopher-CEO.” More recently, Thiel has been at the center of a media firestorm for his role in bankrolling Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit against Gawker, which outed Thiel as gay in 2007 and whose journalists he has described as “terrorists.” He has also garnered some headlines for standing as a delegate for Donald Trump, whose strongman populism seems an odd fit for Thiel’s highbrow libertarianism; he recently reinforced his support for Trump with a speech at the Republican National Convention. Both episodes reflect Thiel’s longstanding conviction that Silicon Valley entrepreneurs should use their wealth to exercise power and reshape society. But to what ends? Thiel’s participation in the 2004 Stanford symposium offers some clues. more...