Like raising kids, there is no handbook that tells you how to make the thousands of decisions and judgment calls that shape what a conference grows into. Seven year into organizing the Theorizing the Web conference, we’re still learning and adapting. In years past, we’ve responded to feedback from our community, making significant changes to our review process (e.g., diversifying our committee and creating a better system to keep the process blind) as well as adopting and enforcing an anti-harassment policy.

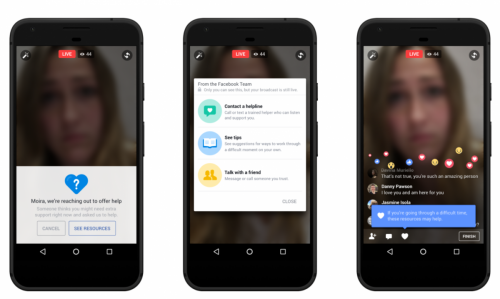

This year, we’ve been thinking a lot about what we can do to ensure that presentations respect the privacy of the populations they are analyzing and respect the context integrity of text, images, video, and other media that presenters include in their presentations. I want to offer my take—and, hopefully, spark a conversation—on this important notion of “context integrity” in presenting research.

In “Privacy as Contextual Integrity,” Helen Nissenbaum observes that each of the various roles and situations that comprise our lives has “a distinct set of norms, which governs its various aspects such as roles, expectations, actions, and practices” and that “appropriating information from one situation and inserting it in another can constitute a violation.” It’s often social scientists’ job to take some things out of context and bring understanding to a broader audience. But, how we do that matters. more...