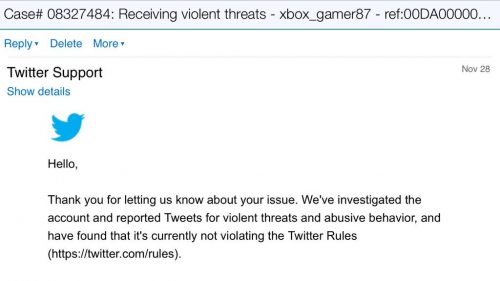

It’s probably appropriate that amidst a torrent of harassment and abuse directed at marginalized people following the election of noted internet troll Donald Trump, Twitter would roll out a new feature that purports to allow users to protect themselves against harassment and abuse and general unwanted interaction and content. Essentially it functions as an extension of the “mute” feature, with broader and more powerful applications. It allows users to block specific keywords from appearing in their notifications, as well as muting conversation threads they’re @ed in, effectively removing themselves.