Is that? Oh my god. The Statue of Liberty, I said in my head, the words hanging in the whirring jet cabin on its descent to LaGuardia. The figure was so small, its features imperceptible and shrouded in shadow – a dark monolith amidst the gently churning Atlantic. The sudden apprehension of our altitude came with a pang of vertigo.

The plane yawed and a second shape swam into my oval window. Is that… the Statue of Liberty? The original figure and its twin were, in fact, a pair of buoys in the bay. I leaned back in my seat and snickered to myself.

It goes without saying that in this instance my sense of scale, perspective and distance, let alone rudimentary geography, were fundamentally (if comically) off.

Finding one’s way in an unfamiliar city for the first time always involves an initial phase of bewilderment: the more familiar one is with their home terrain, the more alien the new place appears. Indeed, across my handful of excursions in and around Queens while attending #TtW16, this distortion pervaded my perception of space.

Queens being laid out in a grid of storefronts and residential apartments that rarely exceed four stories surely makes it one of the more approachable entry points for first-time visitors to New York. And even if it weren’t, with Google Maps, the problem of orienting oneself would seem to have been effectively solved. Spoiler: this is not so!

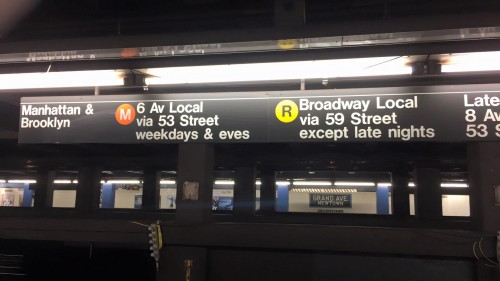

This visit marked my first time traveling outside the Midwest (and the first time leaving my hometown in years) and despite my access to interactive maps and world-class urban planning I still could not get my bearings. Nowhere was my confusion more pronounced than venturing into the subway system. Though my experience of being lost wasn’t limited exclusively to the underground passageways – on the first day, for instance, I couldn’t locate a coffee shop a mere 5 minutes walk from the airbnb – my time in the subways offers as an exceptional case of it.

While getting turned around on the subway, as I did a lot, was mildly disconcerting and at times annoying, I was never scared; losing track of where you are on the subway is essentially a local rite of passage. Still after going in circles around Queens for the second time, I put more faith in Google Maps, as well as a remote interlocutor living in New York: namely my father, who I hadn’t seen since childhood nor spoken with in over a decade.

Riding the subway, swaying as the car shuttered and sparked around me, my only real ‘fear’ was a fear of missing out – on sights and rendezvous. Nonetheless I jumped back and forth between erratically panning around Google Maps for reference points and checking Messenger for the latest directions from my dad. Each stop on the route brought a moment of relief as the internet returned with refreshed location data and new messages, followed by a scramble to process the new information before we started moving again and the connection evaporated back up into the cloud.

Reflecting on the experience of reading my father’s delayed messages alongside Google’s accurate but inscrutable maps, the absent-but-eager dad seems a useful metaphor for characterizing certain interactions with digital devices and services. This ‘dadness’ or paternalism as I see it isn’t the effect of any specific aesthetic choice(s) by the designers as it is a quality that permeates the more utilitarian aspects of smartphones and tools like maps (digital and otherwise). In other words, these tools by dent of their empirical aura, elicit and reinforce a trust in a remote, arbitrary, comforting and pacifying, if no less sought after authority. One that I and many others are quite willing to accept in uncertain situations.

Just as reading my dad’s directions began to take on an absurd metaphorical quality when I failed to apprehend them – I want to understand you but we just can’t seem to connect! – my inability to interpret Google’s subway maps and the various indicators on the subway itself I took, initially, as a personal (if minor) failing. Of course the issue wasn’t (solely) one of personal map reading or of navigation design. Taking the promise of an empirical source as given was inherently naive, though that fact was soon made obvious by my experience; indeed at points I even stuck with Google Maps intentionally just to prove to myself that it was.

Having no good reason to rely on this tool didn’t dissuade me from deferring to it like a novice hiker might refer to a knowingly defective compass: as a pure placebo. By treating the maps, signs, and even my father’s correspondence, as placebos, my mind was freed up to, among other things, disregard them as necessary or as I pleased, to disassociate myself from my trouble following them. Doing so also came in especially handy on the Sunday after TtW, the last day of my stay in New York.

The night before I’d left my bag at the bar and among its contents was my phone charger. I got my bag back from the bar when it opened after noon but my phone had already died. It was 1:30pm when it reached 40% full, but by this time I’d already accepted a meeting with my father might not happen. I was determined to see Manhattan before I left that evening, in no small part because having done so would mean I’d successfully traversed (one small sliver of) the subway. An imminently attainable goal, for sure.

Long story short, having tried out the other “placebos,” I recalled a SciFri interview with a pair of researchers, one of whom had gained notoriety for rendering New York’s subways as circles, breaking from the more literal representations of traditional designs. I opened the circle map for New York on my phone and in minutes I’d located myself and correctly predicted the next stop. It just clicked for me and the feeling was very satisfying. Anyway after a few stops I got off at 40th & Broadway. Coming up the stairs I noticed the buildings were taller right away and one had a video screen running its length. I turned left and there was the Statue of Liberty no lol, but it was Times Square! Half an hour of walking and short rides downtown, I even met up with my dad.

As affirming as having a better grasp of the subway was, to attribute that to the circle maps being that much more intuitive or to myself would be silly and too neat. Yes it was surely a combination of map UX, general acclimation to the subway’s interface, tips from a couple people I met on the subway, guidance from my father, not to mention the reassuring and warm welcome from everyone I’d hung out with at TtW! – but also some amount of dumb luck from trial-and-error and the “image of the city” that I was consciously and unconsciously forming in my mind.

None of which lessened my appreciation for the practical utility of orienting technologies like maps, if less as tools in my case then as placebos, without which it’s hard to imagine even getting “on-line” at all.

Nathan is on Twitter.

Headline Pic via: Source