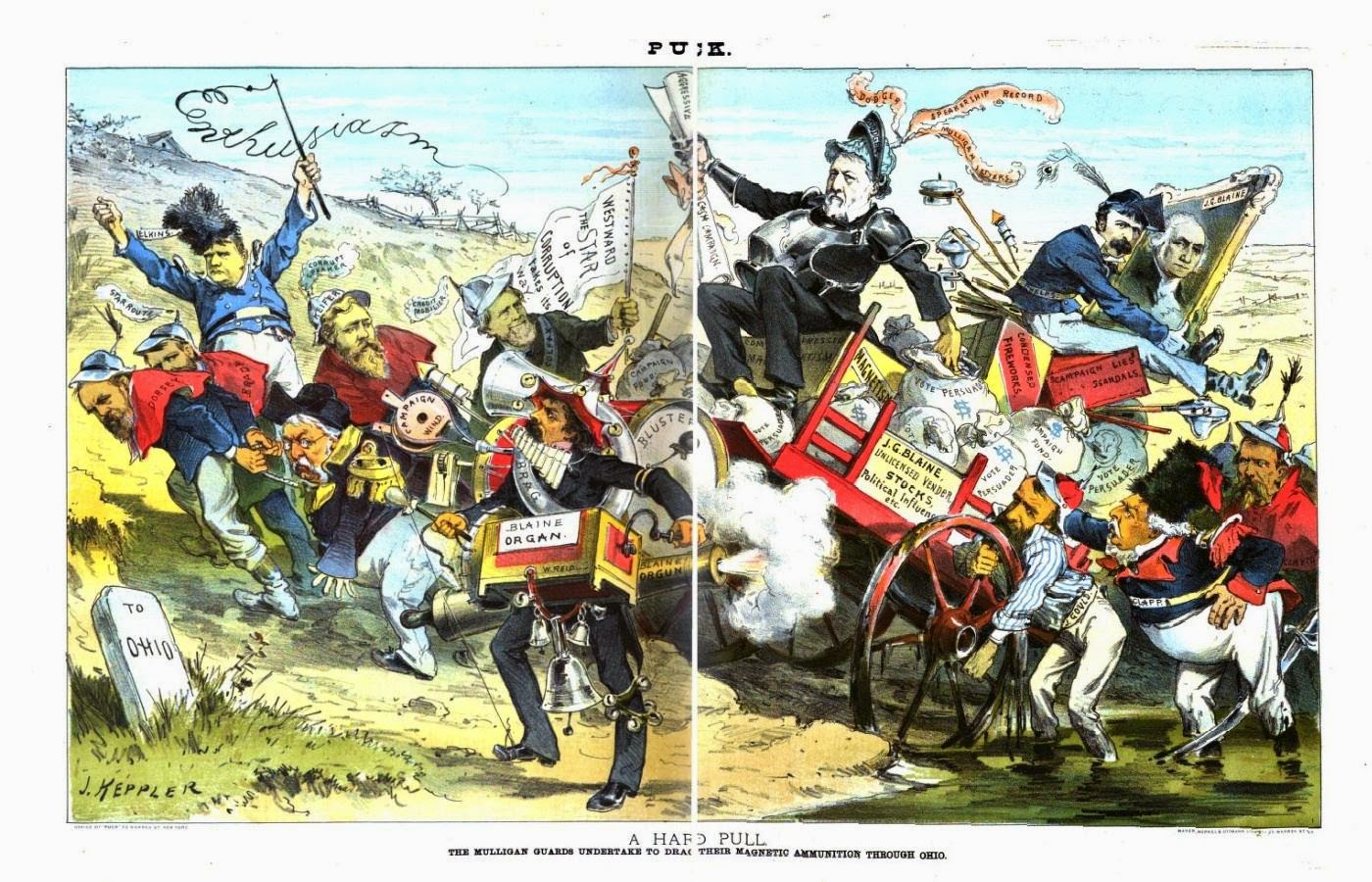

One of the most prominent theorists of the late 20th century, Michel Foucault, spent a career asking his history students to let go of the search for the beginning of an idea. “Origins” become hopelessly confused and muddled with time; they gain accretions that ultimately distort any pure search for the past on the terms of the past. Instead, his alternative was to focus on how these accretions distorted the continuity behind any idea. This method was called “genealogy,” by Nietzsche, and Foucault’s essay expanded on its use. Dawn Shepherd captured the significance of this lesson in a beautiful, single sentence: “Before we had ‘netflix and chill ;)’ we just had ‘netflix and chill.’”

One of the most prominent theorists of the late 20th century, Michel Foucault, spent a career asking his history students to let go of the search for the beginning of an idea. “Origins” become hopelessly confused and muddled with time; they gain accretions that ultimately distort any pure search for the past on the terms of the past. Instead, his alternative was to focus on how these accretions distorted the continuity behind any idea. This method was called “genealogy,” by Nietzsche, and Foucault’s essay expanded on its use. Dawn Shepherd captured the significance of this lesson in a beautiful, single sentence: “Before we had ‘netflix and chill ;)’ we just had ‘netflix and chill.’”

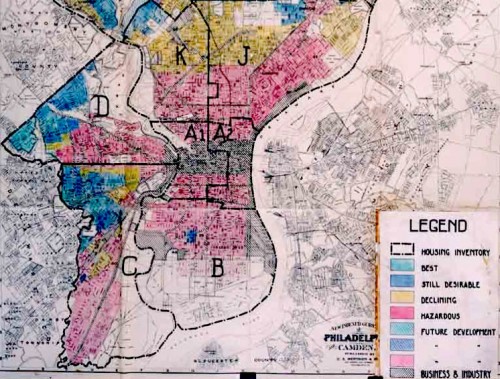

The temptation with something as recent as the web is to emphasize the web’s radical newness. Genealogy asks that we resist this demand and instead carefully think about the web’s continuity with structures far older than the web itself. While genealogy is not about the origins of “chill,” genealogy emphasizes the continuity of “chill.” Genealogy must build from an idea of what “chilling” entailed to say something about what “chill” means now.

Conversations about these continuities animated many of the conversations at Theorizing the Web 2016. Both the keynote panels and regular sessions asked audiences to imagine the web as part of society, rather than outside of it. In the words of its founders, the original premise of the conference was “to understand the Web as part of this one reality, rather than as a virtual addition to the natural.”

It was in 2012 when I first encountered this premise in a course called “Critical Videogame Studies.” This course took seriously the notion that digitality did not exist outside of “real life,” but constituted it. It was an experience that invited me into spaces like Theorizing the Web, where digitality does not need to defend itself in terms of broader historical significance. Just like print culture’s assimilation into European politics, so too has digital culture become more than simply a marginal realm for hackers and geeks.

Pushing against the web as radically new demands discussion about continuity. Inequality, exploitation, and abuse are clear examples of such continuity. Katherine Cross, in #k1, brought them in focus with her description of the robot apocalypse as a guilty memory of the future; the parallels between the Marxist factory worker and the robot––Czech for “forced labor”––shifted by the persistent demand that we gender our sources of labor. TayAI was the most recent in a long history of gendered bots designed according to the historical placement of race and gender into vulnerable labor roles, usually without the ability to say “no.”

Shepherd’s invocation of “netflix and chill,” which happened on #k1, also invokes what is new for a genealogical approach to the web: the idea of “netflix” brings into our heads a deeply intimate connection with our screens, often watched in private, late at night, and alone or with a person of interest. Faith Holland emphasized this new relationship to technology, calling it the “libidinal residue on our screens.”

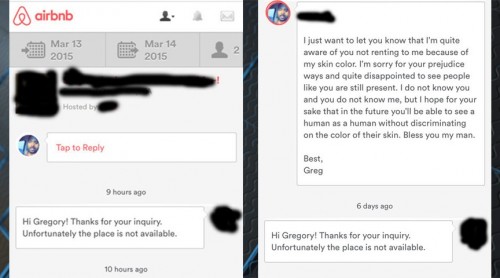

But even with this new element, the web reveals itself to be more reactionary than revolutionary. A central part of Alana Massey’s “Against Chill” essay is a critique of how the “chill” nature of hook-up and dating apps make building investment a deeply gendered game of chicken. To show attraction, to text frequently, to even feel infatuation itself must be regulated by appearing to be “chill.” This is the newest form of an old game: critiquing often feminine-associated affect for not performing to masculine demands.

Whether we want to fuck robots in some post-human sexual fantasy, or are drawn to the fantasy of dominating femininity in the relatively safe space of AI programming, the hybrid nature of the people-tech apparatus has changed both our relationships to technology and our relationships with each other. Thinking about hybridity animates much of our current obsession with cyborgs. But while hybridity is all about coming together in a synthesis, cyborgs can also bring about an anxiety over the prospect of machines’ ability to overtake humanity within the cyborg body. If Minka Stoyanova’s suggestion on #a2––that cyborgism is feminism––is a helpful framework, then it might be better to ask how a politics of empathy might help us develop better habits for how we treat both parts of the cyborg, rather than asking what part we can freely exploit or which part will be dominated by the other.

This demand––to own, to exploit, to command, to impose––are all exertions we’ve projected onto the sphere of AI. Darius Kazemi kicked off #k2 with a search of bots on Medium articles, whose titles reflect this demand:

“Bot is the Wrong Name and Why People Who Think They Are Silly Are Wrong.”

“Software is ‘Eating’ up the World, Part II.”

“We Should All Have Our Own Bot.”

“How to Get Money with Your Telegram Bot.”

“Bot Apps, the Invisible Interface and a 100 Billion Dollar Market.”

Each of these articles follows the disruption narrative: bots are an undervalued market, investing in apps for bot commoditization will yield profits. The “new” conception of a perfect automaton, to exploit for endless amounts of revenue, meets an old understanding of labor’s relation to the market. To paraphrase Marx, capital could not abide the physical limits to its growth. We can interpret our present historical moment as an effort on the part of Silicon Valley to supercede those barriers with digitality. Wherever a new market for apps or quantitative methods appeared underexploited, venture capital and start-ups were more than happy to commoditize even if they had zero expertise, as seen by Jessie Patel and Maggie Mayhem on the proliferation of pregnancy apps in #b3.

If bots currently embody the reactionary nature of capitalism itself, bots also embody the potential of new ways to envision connection. With enough data and the right algorithm, the re-creation of people who died becomes a serious idea, as suggested by Joanne McNeill on #k2. But this possibility is less about whether the bot can do it—it can—and more about whether society can currently take the bot seriously, on its own terms, rather than perpetually asking when it will become “human.”

Questions like “what is new about stories on the web?” are less about what is new about their mediums, and more about the relationship of these mediums to their audiences. Nowhere is this clearer than the relationship between the web and storytelling. The problems of calling something new about digital storytelling is how one judges its veracity. If the definition of “fanfiction” is anything written on FanFiction.net, then the genre is new. If the definition of “fanfiction” is “alternate accounts set in the same universe,” then the Four Gospels of the New Testament become fanfiction. What genealogies of the web ask is “how does the centrality of sites like Fanfiction.net contribute to the normalization of this genre, and have people reacted differently to it?”

One clear difference is how quickly specific non-normative headcanons have caught fire in the fanfiction genre. From the pon farr narratives of Kirk and Spock to the plethora of stories that existed simultaneously in the same universe, fan fiction as a genre has become a productive first step for writers now exploring their own stories and a space for non-normative experiences to make their mark on the science fiction and fantasy worlds.

But Fanfiction.net’s centrality has also given space for reactionary groups to push against these narratives. While the Sad Puppy movement failed to capture the Hugo Awards for several years now, that movement has normalized its own canon, marking Sci-Fi as the genre of “men starting wars on the moon” (quote by Laurie Penny, on #k3). What’s more, The Sad Puppies, much like GamerGate, are not the irrational fragments of a few upset people; they constitute a viable political force, whose reactionary agenda has been well organized and targeted. Taking these movements seriously, genealogy shows just how deeply entwined the digital hopes for liberation are bound by the limits of social imagination.

These digital hopes for liberation had themselves come from the fetishization of a web “origins”: the word was envisioned as central power. Julian Dibbell wrote that words now had the power of action: “a kind of speech that doesn’t so much communicate as make things happen, directly and ineluctably, the same way pulling a trigger does.” Dibbell’s essay focused on making sense of a rape on an MUD—or multi-user dungeon—built on text. This emphasis on the power of words led many to believe that society could finally overcome many of the politics associated with race, gender, and other elements of identity that are difficult to change.

Dibbell’s essay was published in 1993. Over twenty years later, most people recognize that this hope was about as likely as Clifford Stoll’s predictions in Silicon Snake Oil. Writing about the same MUD as Dibbell, Lisa Nakamura emphasized that it was the people using the words who were producing identity, rather than the words themselves. Against an earlier tradition of writers who envisioned the web as something truly different from ourselves, Nakamura’s analysis centered the decisions made by people, rather than the new medium through which those decisions were communicated. By emphasizing the origins of the web as a text-only peripheral communications space, this tradition of early writing on the web could not recognize the agency of the humans whose actions were ultimately determinative in producing older social structures of society online.

By focusing on this agency, the relationships between images, virality, and “evil,” are easier to understand. As Moira Weigel’s introduction of #k4 noted, people have steadily questioned the relationship between the image as a mode for change and the image as mere spectacle since Socrates. #TtW16 dealt directly with this issue in #b6 where a talk on revenge porn freely distributed the images with no censorship of identity, or even consent. One question that came directly from the hashtag was whether or not such a redistribution of images was essential to the study of the phenomenon, or whether it was only an experience of the spectacular, thus complying the audience to re-victimize these targets.

Weigel summarized this dynamic as repetition and cessation: “We have to look at this violent, upsetting, horrible thing, if to acknowledge the horrors of history so that they don’t happen again.”

Is it so clear that looking at an image prevents it from happening again? As Ava Kofman and Jade Davis both invoked on #k4, the simple proliferation of images of violence against Black Bodies––and now the augmented experiences of those in refugee camps or in the aftermath of a police shooting––do relatively little if they are presented as an exhibit, or in a sterilized space where we set these occurrences outside of our own practices in everyday life.

In other words, experiencing these moments of violent behavior are not transformative in themselves; they are either tools we use to envision alternative structures of society that we expend energy to make real, or they are exhibitions that we click, share, or spread in order to feel good about our own levels of awareness compared to our friends. Of course, this binary between tool and exhibition is false, and it is more than likely that each image exists as some combination of both. Genealogy often helps us recognize the gradient of human action that is possible with any given image or text.

When it comes to the nature of evil, however, it is easiest to imagine evil as produced by a single entity, premeditated and clearly defined, with zero room for gradients. We’re used to conceptualizing evil as a single big bad werewolf, whose obliteration is entirely possible through some silver-bullet reform or revolution. Many early dreams of digital utopia hinged on the potential for this obliteration, whether they believed that revolution was anonymity or ease of communication. These dreams were illusions because the evil is in the details. Rather than building a giant ideological entity, traceable through the entirety of history, evil is better thought as the accretion of precise accidents that have snowballed to produce something significant. It was the snowballing of these details that social theorist Hannah Arendt famously termed “the banality of evil” in her writings on the trial of Adolf Eichmann.

In this regard, what is new about the web is precisely its potential for the rapid aggregation of those details on a scale previously unknown. Zeynep Tufekçi, on #k4, positioned this aggregation in terms of how images online are created, and how those images are consumed. The circulation of violent images has no definitive effect in the world: it can embolden people towards more violence or encourage others to end it. Regardless of how powerful or well-intended a set of images are, an intrinsic component of the web is to steadfastly resist whatever story you’d like to tell; on #k3 Kleeman described this steadfast resistance as “the tweet that refuses the primacy of the streamlined narrative.” To borrow Laurie Penny’s phrasing, the existence of “multiple headcanons” online cannot properly translate into politics offline for all their stark oppositions. How do we merge headcanons of post-patriarchy with the headcanons of /r/RedPill?

The answer is also in the details of asking what is new and old about the web and humans on the web. The web is not an apex of hyper-rational modernity whose introduction will tame and educate those people who seem irrational to us; the web is an element of reality, intimately molded by the social and cultural expectations of all people. To theorize the web is to theorize about how we as humans derive meaning and understanding in the world. Focusing on how these precise details, accretions, and accidents produce structures far larger than ourselves is the process of genealogy, and its end result will produce a type of evil far more manageable than the werewolf we currently see.

Marley-Vincent Lindsey is a PhD student at Brown, where he works on religion, economics, and ideas between Spain and Latin America in the sixteenth century. He uses this experience to ask what is new and old about human beings on the web, a question that is very dear to him. He occasionally tweets.

Headline Pic Via: Source