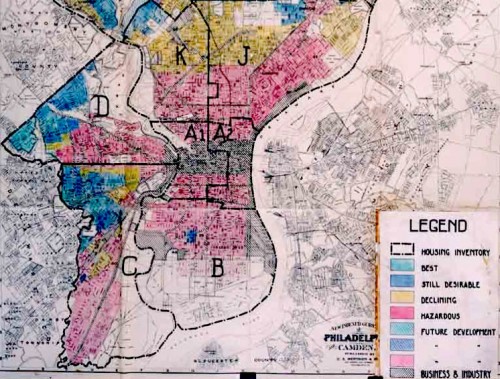

Redlining refers to the racist policy and/or practice of denying services to people of color. The term was coined in the 1960s by sociologist John McKnight and referred to literal red lines overlaid on city maps that designated “secure” versus “insecure” investment regions, distributed largely along racial faults such that banks became disproportionately unwilling to invest in minority communities. In turn, realtors showed different, more desirable properties to White clients than those they showed to clients of color, thereby reinforcing segregation and doing so in a way that perpetuated White advantage. Redlining was outlawed in the 1970s but its direct effects were intergenerational and versions of redlining continue to persist.

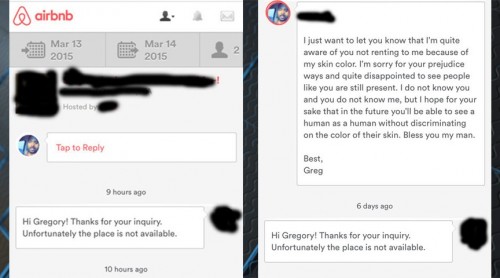

Versions of it like this:

Over the last few weeks, the story of Gregory Selden went viral. Selden attempted to book an Airbnb and was rejected. Noticing that the space was still available, he created two fake profiles using images of White men. Both fake guests were accepted. He confronted the host and the company, to little actionable effect.

Selden’s case, though compelling, is not exceptional. The hashtag #AirbnbWhileBlack emerged in response to Selden’s viral experience, validating the patterned nature of discrimination through the home-sharing site. The stories shared on Twitter fall directly in line with the academic research,which shows that Black guests are 16% less likely to be accepted than their White counterparts, even at a financial cost to Airbnb hosts. In short, many Airbnb hosts do not want Black people to stay in their homes, just as White homeowners and White bankers wanted to keep Black people in separate neighborhoods.

To be sure, the stakes for Airbnb customers who struggle to find vacation accommodation are not so high as families of color who could not purchase homes and were relegated to poorly funded regions and ghettoized into poverty. In this way, discriminatory patterns on Airbnb are more fairly categorized in the hospitality sector than the housing sector and are more akin to the Whites Only lunch counters and hotel policies than mortgage lending practices.

But even the lunch counters and hotels of Jim Crow don’t quite capture what is going on here. Those were explicit forms of discrimination, announced and therefore debatable only in their righteousness, not their existence. People disagreed about whether or not people of color should be admitted to the same establishments as Whites, but all were clear about the fact that people of color were not admitted to these establishments. On Airbnb, the racism itself is an unsettled reality. Indeed, Airbnb tried to explain away Selden’s experience of racism, claiming that the initial rejection was not due to race, but due to Selden booking different dates. They claim that he booked only one night with his real account but booked 2 nights with the fake accounts, and that lots of Airbnb hosts will not rent their space for just 1 night (Selden says Airbnb’s assessment is erroneous, and that he booked the exact same dates and number of nights).

So Maybe it’s more like trying to hail a cab while Black, in which one’s skin becomes conspicuous making services difficult to obtain, but also difficult to prove a racially motivated reason on the part of the service provider. Only with Airbnb, the judgment isn’t so snap. Hosts have time to think about why they elect one customer over another, meaning that hosts have to confront their own racial bias in a way cab drivers may be able to effectively suppress.

Ultimately, the model of Airbnb, and of the share economy in general, is qualitatively different from a hotel or restaurant or even taxi service. In a share economy, financial transactions have a distinctly personal bent. The challenge of regulation is in monitoring lots of individual contractors, who hold little connection to the companies under which they operate, and who have an interest not just in profit, but in maintaining interactional comfort. How does one regulate who people will allow to sleep in their homes?

Racial discrimination on Airbnb is therefore not so much a parallel to historical patterns of racism, but a continuation. This is how racism manifests in today’s version of capitalism. The system looks different, but does the same thing. This is the racism of Google’s photo identification software that identified Black people as “gorillas” and Apple’s racially diverse emojis that not only came after years of White-only options, but appeared as aliens on phones that did not have the latest software running. This is the racial bias of online dating.

As long as race organizes interaction, and does so in a hierarchical way, the goods and services of market capitalism will have racism built in. A sharing economy sounds warmer than the cold tradition of corporate capitalism, but sharing implies a choice on the part of the “sharer,” one that, apparently if unsurprisingly, excludes and marginalizes the “sharees” who have long been pushed out of public and civic life.

Jenny Davis is on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Comments 1

Anonymous — June 3, 2016

It really is surprising to see that racism and discrimination are still going as strong as they are and it's 2016. How long will it take for things like racism to fade away? I also often ask myself why racism is still so potent in the U.S. than anywhere else in the world. Growing up I was told that everyone was equal, that I have the same opportunities as any other kid regardless of race but that isn't the case. So if racism is still around today, will it still be around when my kids are born? Will it ever take a backseat? Or will that be the hidden reputation for the U.S.?